Putin and the $100 million deal that disappeared

The run-up to the recent Russian presidential elections was fraught with controversy. Several papers reported election-rigging, while protesters complained of repression of political opponents. But questions of corruption are nothing new for President-elect Vladimir Putin.

Putin started his career in the KGB, the secret police service that has since become the FSB. After working for several years in Germany, Putin moved to St Petersburg in 1990. There he left the KGB to enter the world of politics, taking up a number of positions within the city hall.

It was not long before questions began to swirl around Putin.

Food for oil

In 1992, Putin was investigated for a deal he oversaw while an official in the mayor’s office. The deal involved the export of $100m worth of raw materials in exchange for food for the citizens of St Petersburg. The materials were exported, but the food never arrived.

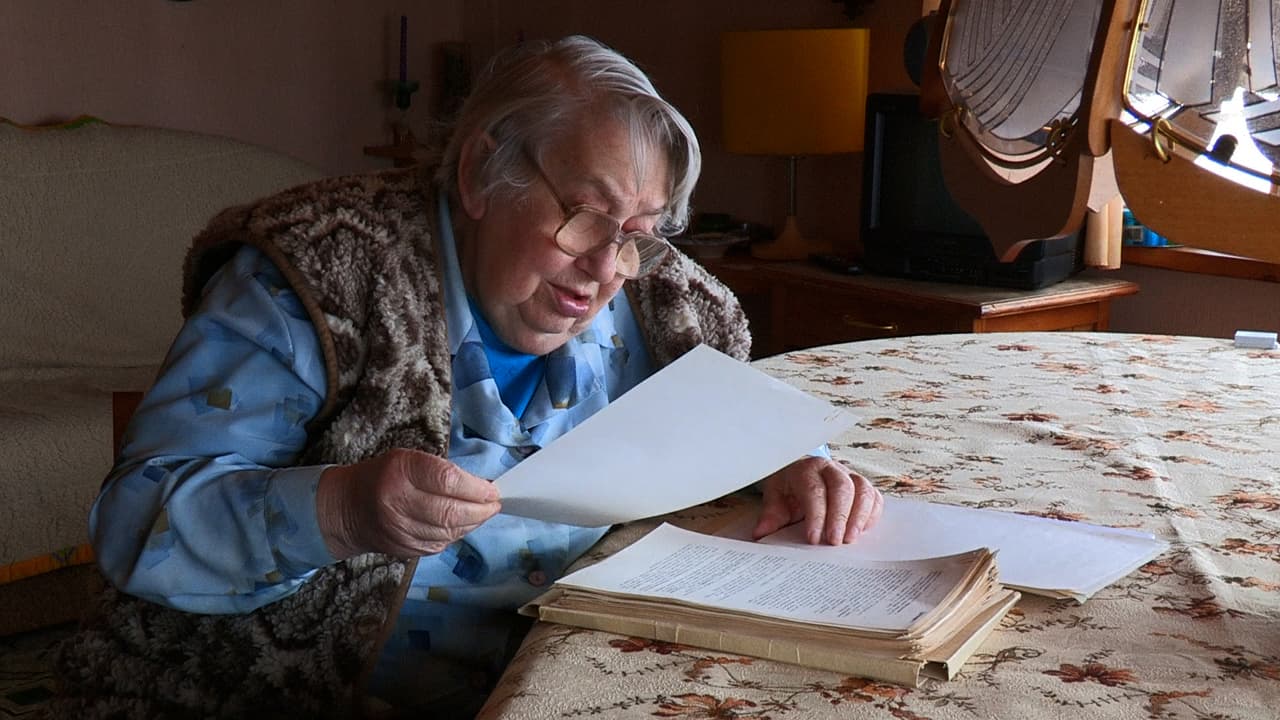

Marine Salye was put in charge of a city council investigation into the deal, and fastidiously kept the documents from that time.

Papers granting export permits to companies involved in the deal appear to show Putin’s signature.

Salye told Bureau reporters working for Al Jazeera’s People and Power: ‘The raw materials were shipped abroad but the food didn’t materialise. There’s 100% proof that in this Putin was to blame. As a result in 1992 – when there was no food at all – the city was left with nothing. The evidence I have is as solid as it gets.’

Salye continued: ‘We also found out that Putin – well, his committee – made bartering contacts to get food for the city. He issued licences. And commodities – wood, metal, cotton, heating oil, and oil – flew out of the country.’

The investigation at the time did not turn up any evidence that Putin had personally benefited from the deal.

The Kremlin denies Putin ever signed the documents.

Salye died of natural causes weeks after talking to the Bureau.

Twentieth Trust

Putin moved on from the oil for food scandal, rising through the ranks and being elected president in 2000, after serving in the role for several months following the resignation of Boris Yeltsin.

Despite his rise, rumours continued to bug the politician.

In June 1999, as Putin prepared for the role of first deputy prime minister, a criminal case was opened looking into his past.

Lt. Col. Andrei Zykov, a former senior investigator at the Russian Interior Ministry, was put in charge of criminal case number 144 128.

Zykov was given the task of investigating a construction company, Twentieth Trust. Officials suspected the company had been used to siphon money from St Petersburg’s city budget in the early 1990s, when Putin worked in the city office.

The company continued to receive government funding despite being in debt.

Zykov told the Bureau, ‘The question was, why? A corporation shouldn’t receive any public money if it is in debt. But it was getting more and more funding. The answer is they were bribing the St Petersburg mayor’s office.’

Unlike Salye’s investigation, Zykov feels Putin did personally benefit from the scheme.

He alleges: ‘We investigated and found out that the Twentieth Trust corporation built a house for Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin on the shores of Lake Komsomolskoye, as well as a villa in Spain,’ said Zykov. Putin’s dacha compound on the banks of the lake was set up by Putin and colleagues in 1996.

However, in 2000, Russia’s prosecutor general shut the investigation down on the grounds of ‘insufficient proof’. Zykov was fired a year and half later.

We asked the Kremlin to respond to Zykov’s claims. It declined to do so.

Sign up for email alerts from the Bureau here.

Header image: Marina Salye looks through the records from her investigation into Putin.