Blowing the whistle on the meat industry

An insider's account of work pressures in the slaughterhouse

Consumers have been exposed to meat contaminated with potentially dangerous bacteria because of poor hygiene practices and ineffective regulations in some UK abattoirs, according to a whistleblower meat inspector.

After 20 years of working in abattoirs - inspecting animal carcasses for disease and making sure safety and hygiene rules are followed - he has decided to speak out. Regular hygiene lapses, coupled with poor regulation, could lead to dirty meat getting into the food chain and endangering human health, he believes. Previously unpublished official reports obtained by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism back up many of his claims.

He said: "The general public have a right to know what goes on before meat comes to the supermarkets...It’s about time something was done."

The allegations come as analysis of official Food Standards Agency (FSA) data reveals more than a quarter of slaughterhouses - 29% - have failed a key hygiene regulation around preventing contamination. Some of the plants are run by companies which supply big brands including M&S, Asda, McDonalds and Waitrose among others.

The findings come as the Government’s consultation over plans to make CCTV mandatory in abattoirs closes on 21 September. Campaigners hope that the plans, which are intended to reduce breaches in animals welfare rules, could also prevent hygiene failings.

A CCTV image of a sheep in an abattoir

via Animal Aid

A CCTV image of a sheep in an abattoir

via Animal Aid

Figures show 90% of slaughterhouses already have CCTV. Yet in 2016 more than 30 abattoirs refused to let FSA vets see film of animals being killed, according to an investigation by The Times, prompting fears that acts of cruelty could be being concealed. Unless the Government forces slaughterhouses to make the footage available to meat hygiene inspectors there will be no improvement in either hygiene practices or incidents of animal cruelty, the Bureau's whistleblower claims.

Major failures in hygiene could lead to meat contaminated with bugs such as E.coli, salmonella and campylobacter being sold for human consumption - which can cause food poisoning. About a million people in the UK each year suffer food-borne illness, according to official estimates. Around 20,000 are admitted to hospital and 500 people die annually. Foods most often linked to food poisoning cases include poultry; vegetables, fruit, nuts and seeds; and beef and lamb.

Although stressing that no meat is completely sterile, food safety experts say that many of the poor practices revealed by the whistleblower and in official reports increase the likelihood of contaminated meat reaching the public, thus increasing the chances of serious food poisoning outbreaks. Professor Hugh Pennington, a leading microbiologist, said "the consequences can be catastrophic".

David Drew, shadow minister for the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, called the findings "very worrying" and said they show mandatory CCTV is urgently needed in abattoirs. It is "ridiculous", he added, that meat hygiene inspectors (MHIs) are not always given access - and this should be remedied. More vets and inspectors are needed in slaughterhouses so the consumer can be reassured plants are meeting expected standards, he added.

The findings come amid fears that regulation around food safety and animal welfare may be relaxed in the near future. There are also fears that such rules may be softened after Brexit, as many are based on European Union regulations.

The FSA said inspectors and vets check carcasses for visible contamination and 99.57% pass the test. It maintains meat with visible contamination "does not enter into the food chain" and that its audit system is "thorough and rigorous".

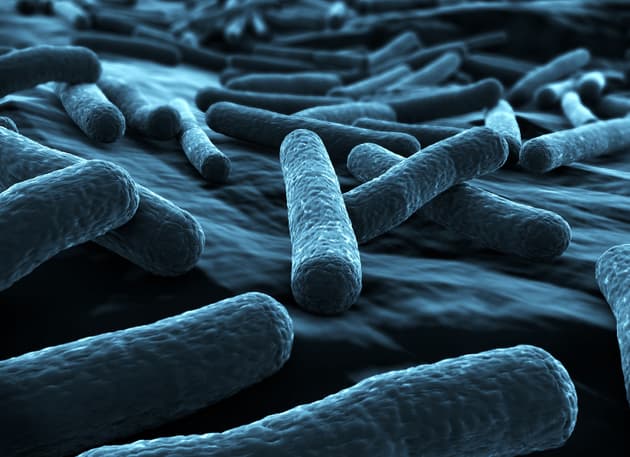

Dangerous food bugs

A strain of E. coli known as O157 is among the most dangerous food-borne illnesses and can cause severe stomach pain, bloody diarrhoea and kidney failure. Although rare, in severe cases it can lead to haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS), which can be fatal, particularly for young children. E. coli O157 is often found in the guts or waste of animals, including cattle, and meat infected during slaughter and processing is one route of transmission.

More than 20 people died during the UK’s worst E. coli O157 outbreak in Scotland in 1996, blamed on contaminated meat. A later outbreak, in South Wales in 2005, saw more than 150 people, many of them children, fall ill and one child die. Dirty meat was again the cause. In 2016 Public Health England (PHE) recorded 712 cases of E.coli 0157, which had fallen by 40% since 2011.

The most common food poisoning bug is campylobacter. Nearly half of supermarket chickens are now infected with campylobacter, the latest FSA testing shows, although this has decreased since last year. PHE data shows there were more than 52,000 cases of campylobacter recorded in 2016 - though this is believed to be an underestimate it is thought as many go unreported. An expert told the Bureau 80% of cases are from food.

Another bug – salmonella – can also be deadly. There were 8,630 cases of salmonella in 2016, rising by 2% since 2011. An earlier study by the FSA found salmonella is the bug that causes the most hospital admissions. Thorough cooking will kill the bacteria, the FSA says. It also advises people not to wash raw meat but instead wash their hands thoroughly with soap after handling it.

E coli bacteria

via Shutterstock

E coli bacteria

via Shutterstock

Inside the meat industry - a whistleblower's account

For much of his career the whistleblower, who has spoken to the Bureau, worked as a meat inspector contracted on behalf of the government's watchdog, the Food Standards Agency (FSA). He has asked to remain anonymous for family reasons and the fear of intimidation.

Drawing on his conversations with other MHIs and vets across the meat industry as a whole, he says they suggest that some staff have been routinely bullied and harassed in their efforts to uphold good practice – and have occasionally even been assaulted. Although there are many good plants eager to improve so they do not get poor audits, there are a significant number of "bad apples".

"The general public need to know that inspectors and vets are dealing with physical and verbal abuse, damage to property," he told the Bureau, saying that it goes on "every day" in parts of the industry and that "it's accepted". He continues: "If someone pushed you up against the wall and battered you verbally in your office you’d be up for a disciplinary or maybe be fired on the spot. In this industry you’re expected to brush it off and come to work the next day."

Official figures from the FSA revealed that between January 2013 and July 2016 inspectors had to be withdrawn from various meat plants for their own safety on 20 occasions, a story we covered in April 2017. Unions, which represent inspectors and vets, say that the problem is widespread. A Unison 2016 survey found nearly two thirds of inspectors and vets had witnessed bullying or harassment at work in the previous year.

The whistleblower worked for several periods from 1998 until the summer of 2016 at Stillmans, a small slaughterhouse in Taunton, Somerset. He claims he witnessed a catalogue of hygiene failings at the plant.

Official documents back up many of his claims. The Bureau has obtained internal Food Standard Agency inspection audits for Stillmans from 2014 to 2017, demonstrating serious hygiene breaches. These audits are not normally made public. The breaches include a significant level of faecal contamination of carcasses, failure to wash knives, and failure to stain animal byproducts so they are identifiable as unfit for human consumption. The failings are "likely to cause the production and handling of unsafe products,” one report said, demanding urgent action.

Poor practice - an industry-wide problem

Stillmans is not an isolated example of poor practice. Audit reports from five other slaughterhouses and one cutting plant (where carcasses are processed) reveal similar problems. A catalogue of major failings were recorded across the plants between 2014 and 2016. A "major non-compliance" - or failing - is one that is likely to compromise public health, animal welfare or that could lead to unsafe or unsuitable food if no action is taken, according to the FSA's own definition.

Failings included carcasses touching the floor and carcasses touching each other, risking cross-contamination. Washing of carcasses, where faecal contamination is removed with water rather than by trimming, was also recorded in at least two other plants, in addition to Stillmans. Industry experts warn that such practices put food safety at risk as washing can spread bacteria and make contamination invisible.

While Stillmans was rated as "improvements necessary" during this period, the other plants were all rated as "generally satisfactory" or "good" overall at this time, despite the major failings.

The numbers on breaches

Visualisation produced by Charles Boutard

The numbers on breaches

Visualisation produced by Charles Boutard

The documents provide a snapshot of a much wider pattern of failure. The Bureau can reveal an overall increase in the number of slaughterhouses in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, dealing with both red meat and poultry, failing a key standard regarding contamination of meat. Our July 2017 analysis of FSA audits of all slaughterhouses show 29% of plants had a major breach of these rules, up from 25% when we analysed them in February. The Bureau also found these failings were reported at some plants run by companies which supply fast food outlets and supermarkets, including Asda, Waitrose, M&S and McDonalds.

The trade body for supermarkets, the British Retail Consortium, said in a statement: "The safety and quality of the products retailers sell is a top priority...The vast majority of businesses were compliant and those identified would already have taken action to correct the issues raised."

The Bureau passed the reports to a range of experts to review. Professor Erik Millstone, from the University of Sussex, said each major breach found poses "a serious threat to public health". He added "Contaminated meat sold from those facilities could have provoked outbreaks of bacterial food poisoning". He is also calling on the FSA to make its audit reports public to drive up standards.

Professor Hugh Pennington, who chaired the official inquiries into those E.coli outbreaks in Wales and Scotland, told the Bureau "major deficiencies" clearly still exist in the slaughterhouse system since his inquiry. He said it was "disappointing" the FSA isn’t "coming down like a ton of bricks" on failing abattoirs.

The findings show there is "shit everywhere" and not enough is being done about faecal contamination, he said. He was particularly concerned about the prospect of meat becoming contaminated after being given the health mark.

"The health mark tells the customer the meat is safe," he told the Bureau. “If there are any chances of contamination afterwards, it makes the health mark meaningless...It really is something the FSA shouldn’t be ignoring.”

The UK still has a higher instance of E.coli 0157 than other countries, he said, and its effects can be fatal. "There are no end of complications happen once you get the bug," he said. "The consequences can be catastrophic. Prevention is so important. For that reason abattoirs need to be on top of their game when it comes to hygiene."

The FSA said it does not tolerate hygiene or animal welfare breaches. Prosecutions for failures by businesses have increased over recent years, and since the start of 2016. Investigations into offences at meat plants have resulted in 20 convictions, it added.

It undertakes "thorough and rigorous audits" and as a result non-compliances seen on the day and reported by staff during the audit period mean most entries on a report will represent historical findings.

"Anything that poses an immediate food safety risk prompts instant action by FSA officials to prevent that meat entering the food chain. Any practices that could potentially pose a risk in the future to food safety are dealt with in a timely manner, and in the most proportionate and appropriate way to ensure consumer safety."

How meat industry inspection should work

There are more than 300 approved slaughterhouses in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, as well as meat processing plants. Each abattoir, at present, has a permanent FSA vet onsite to monitor day-to-day processing. There are around 850 meat hygiene inspectors and OV’s working in abattoirs and cutting plants in England & Wales.

In addition, a team of specialist, external auditors from the FSA carry out more detailed inspections to determine overall compliance with food law and hygiene standards.

The inspections take place on a rolling basis, with audit frequency being dependent on a plant's previous performance. Auditors - an in-house team of inspectors trained by the FSA to carry out these inspections - record any non compliances found, rating them as minor, major or critical depending on the severity of the problem.

Minimising the risk of meat becoming contaminated with faecal matter is a priority. Livestock can become caked with faeces on farms or during transport to slaughter and this can be transferred to carcasses during processing, particularly during the removal of an animal’s hide or fleece.

Bacteria can then be spread via knives used to cut into carcasses from the hands, arms and other equipment used by abattoir workers, as well as by contact between the fleece or skin and meat tissues. Carcasses can also become contaminated during evisceration - the removal of an animal’s internal organs - when bacteria from an animal’s guts can be spread to other areas.

A system under pressure

Pressure is coming from three key sources - from government, with its drive towards lighter-touch regulation, pressure from the meat industry and, lastly, that the regulator itself is trying to save money.

Unions claim the FSA is already considering changes to abattoir regulation. It is currently rewriting policy around how food businesses will be regulated in the future.

In 2016 the FSA consulted on whether it should relax the auditing regime of some abattoirs, cutting the overall number of inspections in order to reduce the burden on meat processors, which would save the regulator money. Under proposals being considered, slaughterhouses found to be consistently compliant with regulations would be subject to a full audit every 36 months. At present the most compliant premises face re-auditing after 18 months.

In another move towards what critics say is lighter-touch regulation, the FSA may also be moving away from having a permanent official vet (OV) on site at all times; the Bureau has learnt that there has recently been a pilot trial underway in the West Midlands, where a single OV is spread between a number of different poultry plants - reducing time spent on each factory floor. Although the Bureau understands the trial has finished, union sources fear it could be a sign of things to come.

Union leaders say both these proposals could fundamentally undermine the FSA’s core principles, of balancing the rights of consumers to enjoy safe and healthy meat with the commercial concerns of food producers. Unions worry that the plans are tantamount to allowing the industry to regulate itself, which fails to recognise the reality of meat production and the hazards it poses to public health.

Paul Bell, Unison National Officer for Meat Hygiene Inspectors, said: “The first and main thing the FSA can do is simply recruit new MHIs. They have told us that they will not recruit new ones. This is to reduce their workforce... Unison has warned the FSA of the consequences of this many times, only to be told we need to grow up and live in the real world. The real world is, I am afraid, full of cost cutting, profit driven motives that put animal welfare and a clean product second in the priority list."

The risk of dirty meat

The whistleblower’s motivation stems from the wider picture, of an industry lobbying for lighter-touch regulation, frequent breaches in standards as well as individual cases of harassment and personal experience.

Stillmans, where he worked, claims to be the UK’s longest established butcher, trading since 1935. It also has a long history as an abattoir. It is well known across the South West, supplying up to 60 butchers and wholesalers, as well as restaurants and catering companies.

The whistleblower said processes he witnessed at the plant meant dirty meat could enter the food chain. After carcasses were stamped with the health mark, they were sent to a designated chiller fridge to be stored before being re-inspected by the OV and transported to customers. Yet he says workers - often "covered with faecal matter and gut contents" - sometimes wandered into this fridge if they needed a pencil or to use the scales, even though they had been told this could re-contaminate the meat.

He added that workers could walk "from the lairage [the area where animals are skinned] into the abattoir, right through the system into the fridges where the meat has been health marked without being questioned. Well, being questioned, but they’d just tell us where to go," he said. The official FSA audit reports for Stillmans show inspectors noted “slaughterman walking from dirty to clean area” in 2015 and flagged this up as a major breach.

The reports highlighted many other examples of poor practice. At least one major breach was found in every audit from 2014 to 2017 and the plant was rated as “improvement necessary”. High levels of faecal contamination were found on pig, sheep and cattle carcasses, to the point that the contamination could be seen by the naked eye. Inspectors also noted carcasses touching the dirty floor, cattle tongues being washed in the same sink that staff used to wash their hands. The area where cattle heads were inspected for diseases had no soap for washing hands.

The whistleblower's key concern at the plant was about dirty carcasses. Stillmans is one of approximately half a dozen abattoirs in the UK which holds a Defra contract to slaughter "reactor" cattle - cows that have tested positive for bovine tuberculosis (bTB), or are suspected of carrying the disease, or have come into direct contact with other infected animals. These cows should be slaughtered separately from other carcasses, with strict hygiene precautions taken to avoid contamination.

Inspectors check them for lesions, which are an indicator of whether the animal has the disease. Depending on the number and location of the lesions the meat can still be sent for human consumption after inspection and processing as there is little or no risk to humans if it is thoroughly cooked.

The whistleblower, however, claims cattle with bTB at times arrived filthy, straight from pasture, with their guts full. This meant that when the animals’ intestines and internal organs were removed during inspection it was difficult not to nick the bowels with a knife and spray gut contents everywhere, contaminating the carcass.

He visited the Devon Country Show this year, and was astonished by how hard farmers worked to groom and prepare their livestock for the event, contrasting with what he had at times seen at the slaughterhouse. “When it’s important for contamination, when they’re going into the food chain, they’re not bothered about them at all. They just come in and they are filthy, they really are," he says. He adds, “if you’ve got animals coming in caked in shit, it doesn’t matter how slow or how good you are, there’s going to be something on that carcass.”

The audit reports also say inspectors witnessed workers washing the anus of a cow while it was being skinned, risking bacteria being spread elsewhere on the carcass. The FSA says if carcasses are visibly contaminated they should be trimmed off with a saw, rather than washed. Yet the whistleblower saw contamination being washed off at Stillmans. “It goes all over and then you get contamination you can’t see,” he said “It is microscopic and suddenly you can’t see it and it’s everywhere”.

An FSA audit report from 2017 says inspectors documented staff washing aprons and knives with a hosepipe, splashing bacteria-filled water next to carcasses. They also noted in the same report some staff weren’t washing their hands, knives or equipment frequently enough.

Inspectors reported particular concerns about the products they found in the chiller fridge for pet food. Bovine stomachs, horse hooves and horse-hide were neither identified nor clearly labelled as animal byproducts and therefore designated as unfit for human consumption. Cattle livers and lungs, skinned lambs’ heads and milk containers filled with blood were stored in the chiller, with no documentation. Staff had no idea where they had come from or to whom they were being sent, inspectors found.

They flagged this as a major issue, explaining that there was a risk that these products might reach the human food chain. Elsewhere, products with a high risk of transmitting disease to humans, such as a cow’s spinal cord or carcasses from a diseased animal, were not stained with dye, in a breach of regulation. (Staining marks these high risk products indelibly, so they are not accidentally sent for human consumption.)

One knife steriliser was not turned on, while very dirty knives were found in another. Sterilisers were found to be below the correct temperature, running the risk the knives were not being sterilised at all. The slaughterhouse itself was found to be dirty; inspectors found substances, including pig hair, blood, fat and mould on fridge walls, railings and hooks used to hang meat.

In a June statement Stillmans said the allegations were "ancient history" and maintained there was "no scientific evidence that washing has any adverse effect on disease organisms[…]". This contradicts what the FSA told the Bureau in a statement. It said: "washing of carcasses must not be done to remove visible contamination as this may have the effect of dispersing the contamination to other parts of the carcass."

The Stillmans statement continued: "Any insinuation that the hygienic quality of our meat is in any way inferior to that from any other abattoir is unsubstantiated and untrue."

It continued: "An FSA veterinary surgeon is present in our plant at all times during operations and the suggestion that any meat which was in any way unfit might leave the plant is not only ridiculous but offensive to the FSA."

It added its "own tests" indicate "freedom from disease causing organisms."

The Bureau contacted Stillmans again in September regarding the whistleblower’s allegations but the abattoir declined to send a response.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with us

The regulator's response

In a statement, the FSA said when the plant was flagged as failing in 2014, a second official vet was sent there to supervise procedures and help with inspections. Official notices were served in 2017, ordering Stillmans to improve practices or face further action which could include being investigated or even prosecuted. Senior FSA vets visited on a weekly basis and had meetings about what was expected.

In March 2017 a further inspection took place to see if Stillmans could keep its approval status, meaning that if serious deficiencies were found, its operations licence would be suspended. The FSA said that Stillmans corrected the problems that had been raised and further serious deficiencies were not found. Stillmans was therefore allowed to continue operating. Its rating has now improved from "improvements necessary" to "generally satisfactory" - which should mean it is audited every 12 months but it is still inspected every three months to ensure historical breaches are being fixed.

"FSA vets and operational managers have spent a significant amount of time working with the food business to improve standards and this is reflected in the current audit rating of “generally satisfactory”, the FSA statement said.

Beef carcasses hanging in an abattoir

Stock image via Shutterstock

Beef carcasses hanging in an abattoir

Stock image via Shutterstock

Although Stillmans had the highest number of breaches in the reports the Bureau obtained, we found that other abattoirs and cutting practices also had poor practice. These plants supply hotels and caterers, including celebrity chefs.

Martin’s Meats, a Cheltenham-based butchery, had one major breach when inspected in November 2016. A beef flank was found at a temperature higher than the legal limit, meaning bacteria could breed and lead “to the production of unsafe product,” said inspectors. This followed a major breach in 2014, when inspectors said there was no evidence that temperatures for sausages and burgers were being controlled properly. Martin’s Meats declined to comment on the breaches raised in the audit reports. In its latest November 2016 audit Martin’s Meats was rated as ‘generally satisfactory’.

Cig Calon Cymru, a Carmarthenshire-based abattoir, was also named.

The FSA identified a string of breaches at Cig Calon Cymru in 2015 and 2016. These included animal byproducts touching carcasses awaiting processing, carcasses touching the floor, and condensation in the chiller where meat was kept. There were 17 other minor breaches recorded in the 2016 report, including pieces of a spinal cord being found inside a carcass, cattle tonsils being stored in the wrong container and meat containers leaking.

In a statement Cig Calon Cymru said these minor incidents related to a small number of carcasses "less than 0.008% of the total throughput of the plant".

It went on to say that the management "is constantly seeking to improve its processes and standards. This thorough engagement with the regulator, continued professional development and training and zero tolerance of any staff member who fails to reach the high standards expected." In its latest audit in April 2017 Cig Calon Cymru received a ‘good’ rating.

Between 2014-2016 the FSA also identified a range of breaches during audits of R J Trevarthen Wholesale Butchers, in Cornwall; Beesons Ltd, in Cheshire; Pembrokeshire Abattoir Limited, in west Wales - which has now closed - and T G Sargeant and Sons, in Staffordshire.

In its latest audit in May 2017, Beesons was rated as "good". "Our audit scores are above average for the industry at large", Frederick Beeson told the Bureau in a statement.

TG Sargeant was also rated as "good" in an audit in June 2017. In reference to the past breaches, Jane Sargeant said the audit process for abattoirs is particularly demanding. "Most businesses when audited only have to put on a show every few months whereas an abattoir is scrutinised continuously by several FSA staff", she said.

R J Trevarthen was rated as "generally satisfactory" in its latest audit in October 2016. In a statement the company said all of the issues raised have been addressed since the audits "in a timely manner following full investigations to the satisfaction of the FSA". He has not received reports of these issues re-occurring.

Pembrokeshire Abattoirs Ltd has been dissolved and we were unable to contact the directors for comment.

Reforming the meat industry

The meat industry is worth £7.3 billion a year, according to the FSA. Yet politicians, food safety experts and the whistleblower agree a serious rehaul of the system is needed to make it fit for purpose.

Prof Millstone called for the FSA to create a labelling system on meat packaging, which would indicate to the consumer whether the abattoir has followed food safety standards.

Audit reports from plants should be published in full, he added. "Hygiene standards would rise very rapidly, and firms that failed to provide good hygiene would go out of business" if these actions were taken, he said, adding that food poisoning cases would rapidly decline.

David Drew, shadow Defra secretary, called on the FSA to reverse the current freeze on the numbers of meat hygiene inspectors. If these "worrying" breaches occur during audits "it begs the question, what’s happening when the audits aren’t going on?" he told the Bureau.

Paul Bell, from Unison, warned that “lighter touch inspection means no daily inspection. It means no one on site to monitor what the producer is doing...Only someone watching what they are doing, has the right skills to know what to look for and whom has the power to stop them, can keep us safe.”

The whistleblower agreed, adding the perceived culture of bullying and harassment they [meat inspectors] face in some plants simply for highlighting breaches of food safety regulations needs to be urgently stopped. More pressure should be put on farmers to make sure livestock is brought in clean - with fines if they arrive dirty. They should be starved overnight so there is nothing in their bellies while they are skinned and inspected. More surprise inspections of plants would give a more realistic view of the routine breaches that are happening, he said.

Mandatory CCTV cameras in abattoirs would be an "important breakthrough", he said, acting as a deterrent against both animal welfare and hygiene breaches. But it is crucial the meat industry do not own or control the footage; that MHI can freely access it. "If it’s going to be a closed shop like everything else, what’s the point?" he said.

If you have any information on this story, contact the Bureau at [email protected] or [email protected] or phone us on 0203 892 7490. Your information will be treated in strictest confidence.

Main stock image, of the interior of an abattoir, via Shutterstock