Dying Homeless: Counting the deaths of homeless people across the UK

Dying Homeless was a year-long project by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism that counted the number of people who died homeless in the UK.

We counted deaths that occurred between October 1, 2017 and March 31, 2019. In that time, we logged the stories of 800 men and women that died while sleeping rough or living in temporary accommodation.

We started the project after learning that no one body logged how and when homeless people were dying, despite a steep increase in the UK’s homeless population. We set out to record these deaths, tell their stories and increase transparency.

We collaborated with local reporters, charities and grassroots groups all over the country to compile this first-of-its-kind dataset. You can see the powerful reporting from our local reporting network here.

In December 2018, prompted in part by our work, the Office for National Statistics started to produce official data on homeless deaths in England and Wales.

We wanted to make sure the stories of those who die homeless continued to be told, alongside the collection of the data. To that end we were delighted to hand over our Dying Homeless project to Museum of Homelessness, on April 1, 2019. Find out more here.

Join the discussion: #makethemcount

If you know of a homeless person that passed away, please let us know

Report a death hereAbout the project

The number of people sleeping rough rose by 169% between 2010 and 2017.

During the bitter cold of the 2017-2018 winter, some deaths made headlines, including that of a man who died close to the Palace of Westminster.

Despite many vulnerable people being known to the authorities, local journalists and charities were often the only ones that reported these deaths.

The Bureau spoke to councils, hospitals, coroners' offices, police forces and NGOs. While there is a charitable network recording information on people sleeping rough in London, we found that there was no centralised record of when and how people died homeless across the UK.

We scoured local press reports, surveyed dozens of homelessness charities, interviewed doctors and other experts to pull together a list of known deaths. There is no obligation on councils or coroners to log these deaths. Therefore our count, sourced from publicly available information, was likely an underestimate.

We asked those working directly with homeless people, as well as our hundreds-strong network of local journalists, to advise us when they heard of a new death.

Where possible, we gathered information from police, coroners’ inquests and family members to fill in the details of the lives, and deaths, of each person. We attended funerals, inquests and travelled the country, undertaking scores of interviews.

We used the same definition as that used by homeless charity Crisis; it defines someone as homeless if they are sleeping rough, or in emergency or temporary accommodation such as hostels and B&Bs, or sofa-surfing. In Northern Ireland, we were able to count the deaths of people registered as officially homeless by the Housing Executive, most of whom were in temporary accommodation while they waited to be housed.

When we were passed a name by the public, we only published it if it had been verified by local homelessness charities, the coroner’s office or other officials.

We recognised that there was often no clear-cut cause for many of these deaths, and that this was both a highly sensitive and complex issue. We committed to recording these deaths in a respectful and nuanced manner and we redacted sensitive information where necessary or requested by the family. We asked those who used our database to do the same.

On October 8, 2018 the Office for National Statistics announced it would start producing its own figure on homeless deaths.

From April 1, 2019 the Museum of Homelessness took on the collation of people’s stories, to ensure these lives are remembered and lessons continue to be learnt.

Note: The text on this page was updated at the conclusion of the project to make it clear the year-long investigation had concluded and to give information on what would happen next.

Thanks to Nathalie Bloomer for additional reporting.

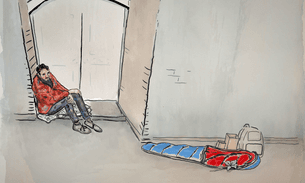

Header illustration by Andrew Garthwaite.