The Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) explained

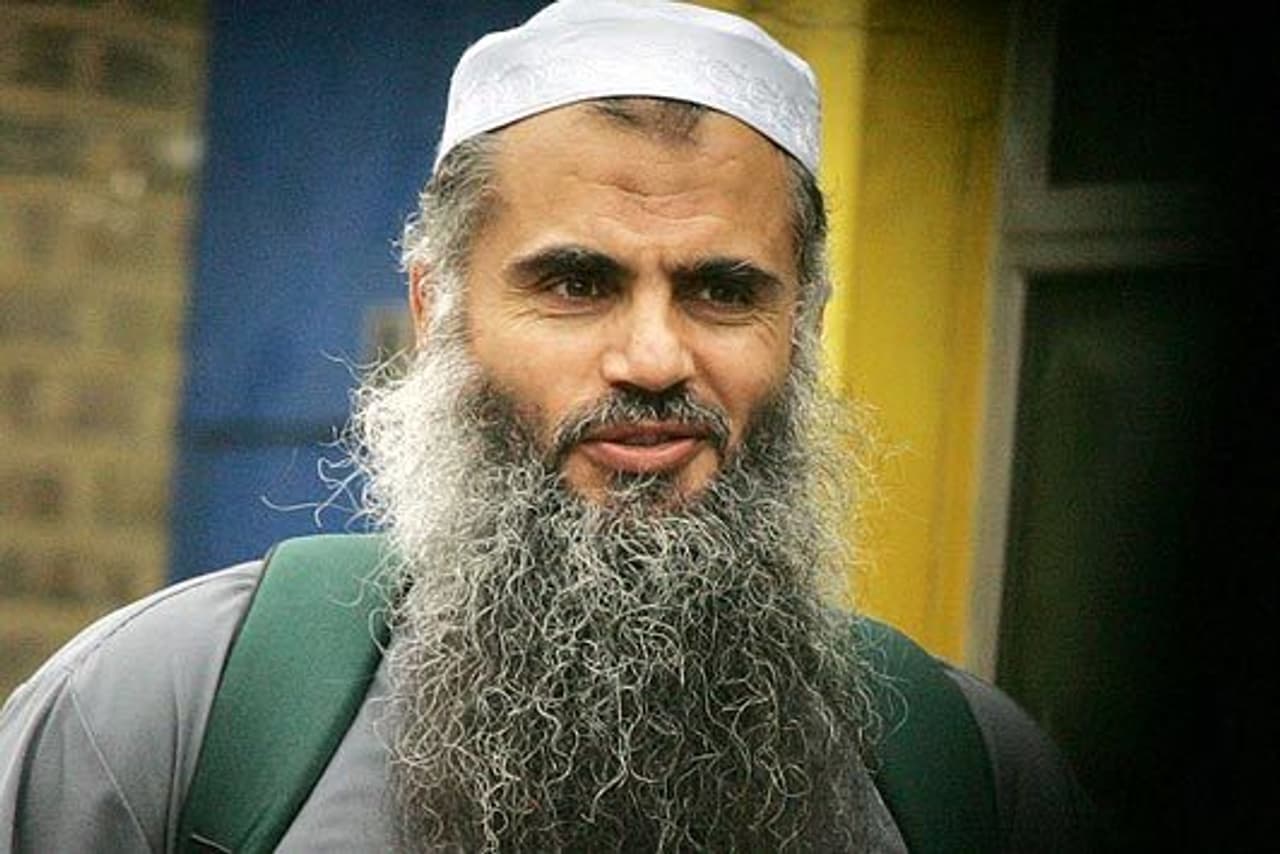

Abu Qatada: the poster-child of SIAC. Not something you’d want to be.

The Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) was established in 1997 to deal with national security deportation cases. The commission works as a court of appeal for those under deportation orders from the Home Secretary, or those excluded from the UK.

However, it is really only in recent months that the commission has made the news, with a number of high profile cases attracting attention. The most high profile case currently before SIAC relates to radical cleric Abu Qatada, described by the government as a ‘truly dangerous individual’.

Before 9/11 SIAC was rarely used as deportations of this nature were few and far between. However, the 2001 Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act enabled the Home Secretary the power to detain, without charge or trial, foreign nationals who were suspected of terrorism-related offences. In the months that followed, 14 suspects were arrested. 12 of these would be held in Belmarsh high security prison before bringing appeals before SIAC.

Since 2001, the court has heard at least 70 cases.

Secret evidence

One of the most controversial aspects of SIAC proceedings is its use of ‘closed’, or ‘secret’, evidence. When the Home Secretary detains a suspect, they may notify the Attorney General that their decision has been partly based on intelligence that they would rather not reveal in an open court. This can include reports by the security services, testimonies from informers within terrorist organizations, or material acquired through phone tapping.

If the judge accepts this argument, the sensitive material will be presented in a closed-door session where it can only be viewed by the judge and security-vetted Special Advocates to represent the prosecution and defence teams. The Special Advocates are then permitted to communicate a loose outline, or ‘gist’, of the evidence to their client, a process which critics claim leaves many defendants in the dark as to the nature of the charges against them.

Prior to September 11th 2001, SIAC had only ruled on three cases that used closed evidence. Over the past decade, such evidence has played a part in the majority of cases that have come before the court. In some instances, the entirety of the substantive case against the detainee has been heard behind closed doors.

A new report by Amnesty International has detailed the difficulties that legal teams face in addressing the charges disclosed in secret evidence hearings. These include the question of how to effectively represent a client without access to substantial parts of the evidence against them, the fear that adopting a certain line of questioning might result in negative consequences in the secret part of the hearing, and large disparity in terms of their ability, compared with the government lawyers, to effectively cross-examine witnesses.

SIAC proceedings have been designed to prevent appellants taking further judicial reviews of the Home Secretary’s decision to deport them. If someone loses their appeal, they retain the right to escalate the matter to the House of Lords, but only on a point of law.