A game of chicken: how Indian poultry farming is creating global superbugs

On a farm in the Rangareddy district in India, near the southern metropolis of Hyderabad, a clutch of chicks has just been delivered. Some 5,000 birds peck at one another, loitering around a warehouse which will become cramped as they grow. Outside the shed, stacks of bags contain the feed they will eat during their five-week-long lives. Some of them gulp down a yellow liquid from plastic containers - a sugar water fed to the chicks from the moment they arrive, the farm caretaker explains. “Now the supervisor will come,” she adds, “and we will have to start with whatever medicines he would ask us to give the chicks.”

The medicines are antibiotics, given to the birds to protect them against diseases or to make them gain weight faster so more can be grown each year at greater profit. One drug typically given this way is colistin. Doctors call it the “last hope” antibiotic because it is used to treat patients who are critically ill with infections which have become resistant to nearly all other drugs. The World Health Organisation has called for the use of such antibiotics, which it calls “critically important to human medicine”, to be restricted in animals and banned as growth promoters. Their continued use in farming increases the chance bacteria will develop resistance to them, leaving them useless when treating patients.

Yet thousands of tonnes of veterinary colistin was shipped to countries including Vietnam, India, South Korea and Russia in 2016, the Bureau can reveal. In India at least five animal pharmaceutical companies are openly advertising products containing colistin as growth promoters.

One of these companies, Venky’s, is also a major poultry producer. Apart from selling animal medicines and creating its own chicken meals, it also supplies meat directly and indirectly to fast food chains in India such as KFC, McDonald’s, Pizza Hut and Dominos.

In Britain, Venky’s is best known for having bought the football club Blackburn Rovers in 2010. They made a TV advert showing the team eating a Venky’s chicken dinner before playing a match with the slogan “Good for you”. Since then Blackburn Rovers has dropped out of the Premiership, been relegated again, and is now in the third tier of English football - with fans protesting the club’s decline.

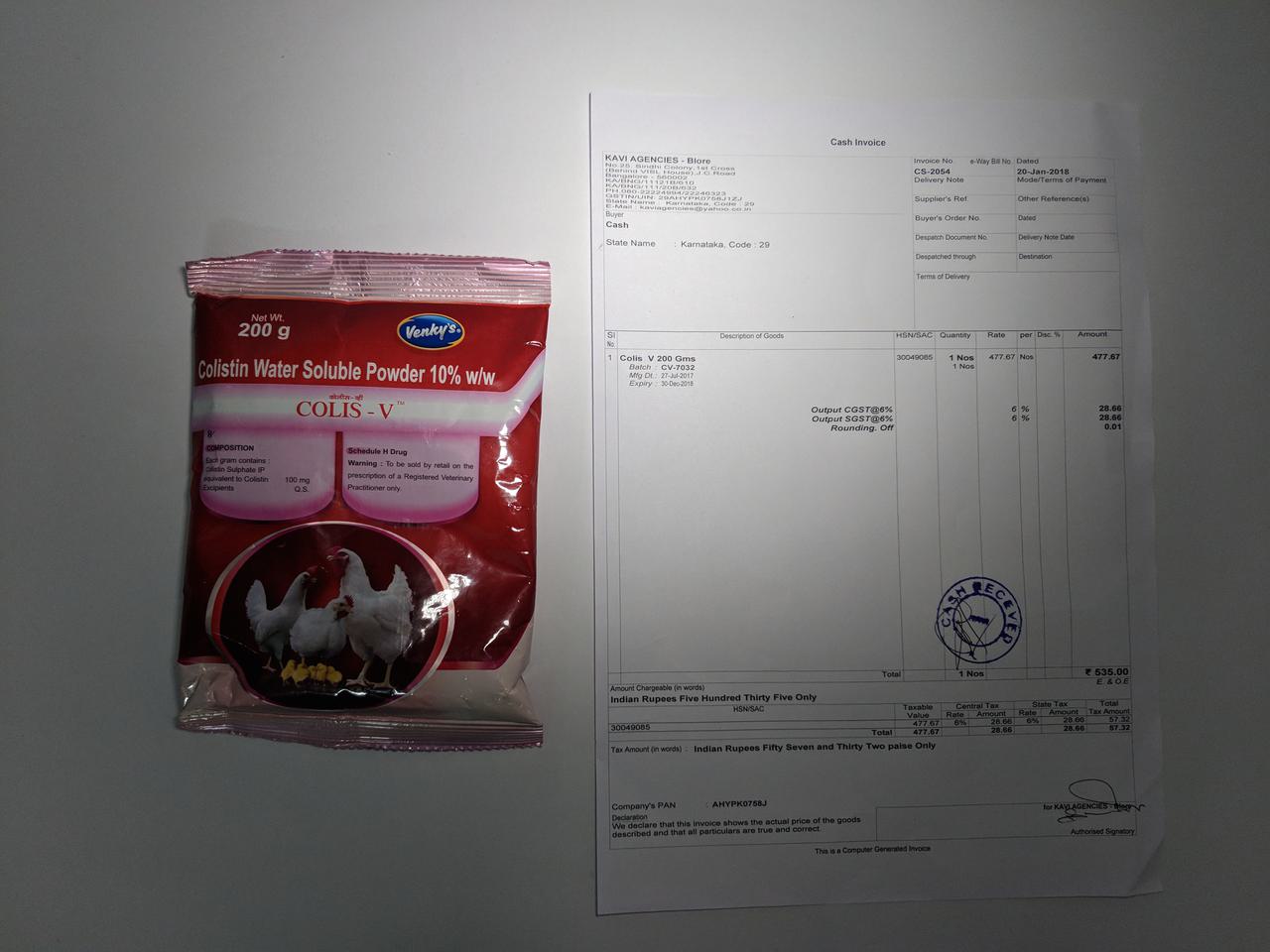

Venky’s sells colistin to farmers in India as a growth promoter. It comes in bags with pictures of happy-looking chickens on the packet. Instructions say the product “improves weight gain” and 50 grams should be added to each ton of chicken feed. The Bureau bought 200g of Venky’s-branded colistin - Colis V - over the counter from a poultry feed and medicines shop in Bangalore without a prescription. In Europe colistin is only available to farmers if prescribed by a vet for the treatment of sick animals.

Venky’s is not breaking any laws in India by selling colistin and it said it will comply with any future regulatory changes. The company told the Bureau: “Our antibiotic products are for therapeutic use – although some of these in mild doses can be used at a preventive level, which in turn may act as growth promoters [...]We do not encourage indiscriminate use of antibiotics.”

Venky’s also exported colistin to Nepal and Yemen last year, customs data show. Other poultry companies are selling colistin products or importing it for use on farms, according to the data.

Venky’s also told the Bureau that on their own farms and those of their contractors “antibiotics are used only for therapeutic purpose”.

McDonalds, KFC, Pizza Hut and Dominos said the chicken they source from Venky’s is not raised on growth promoting antibiotics and their suppliers follow their policies controlling their use of antibiotics.

McDonald’s has pledged to phase out the use of critically important antibiotics by 2018 for markets including the European Union (EU) and US - with an extra year for phasing out colistin in Europe. KFC has made a similar promise about its US supply chains. They have promised to do the same in India but without giving any timeframe, a move the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment has labelled ‘double standards’. Only Jubilant FoodWorks (which owns Domino’s) has set a date, of 2019, to start phasing out the drugs.

Timothy Walsh, a global expert on antibiotic resistance, called the Bureau’s findings about the ready availability of colistin in India “deeply worrying” and described the use of colistin in poultry farming as “complete and utter madness”. Walsh, who is Professor of Medical Microbiology at Cardiff University, and his Chinese colleagues discovered a colistin-resistant gene in Chinese pigs in 2015. The gene, mcr-1, could be transferred within and between species of bacteria. That meant that microbes did not have to develop resistance themselves, they could become resistant just by acquiring the mcr-1 gene.

The discovery was met with worldwide panic in the medical community as it meant the resistance could be passed to bugs which are already multi-drug resistant, leading to untreatable infections. Rampant use of the drug in livestock farming has been cited as the most likely way mcr-1 was spread. It has been detected in bacteria from animals and humans in more than 30 countries, spanning four continents. Another four colistin resistant genes (mcr-2 to mcr-5) have been discovered since. Colistin-resistant bacteria, once rare, are now widespread.

“Colistin is the last line of defence”, said Professor Walsh, who is also an adviser to the UN on antimicrobial resistance. “It is the only drug we have left to treat critically ill patients with a carbapenem-resistant infection. Giving it to chickens as feed is crazy.”

“Colistin-resistant bacteria will spread on the chicken farms, in the air surrounding them, contaminate the meat, spread to the farm workers, and through their faeces flies will spread it over large distances”, he continued.

He added: “Colistin should only be used on very sick patients. Under any other circumstances it should be thought of and treated as an environmental toxin. It should be labelled as such. It should not be exported all over the world to be used in chicken feed.”

Professor Dame Sally Davies, England’s chief medical officer, also called for a worldwide ban on the use of not just colistin but all antibiotics as growth promoters. “If we have not banned growth promotion within five years we will have failed the global community”, she told the Bureau.

An image of Klebsiella Pneumoniae

Creative Commons licence

An image of Klebsiella Pneumoniae

Creative Commons licence

The global superbug crisis

Drug resistance has been called one of the biggest threats to global health, food security, and development by the World Health Organisation. If antimicrobials stop working, doctors won’t have effective drugs to treat deadly infections. Currently the problem is thought to kill 700,000 people worldwide - one person a minute - though these figures have been disputed by some academics. The death toll is expected to rise to 10 million by 2050 if no action is taken, with 4.7m of those deaths in Asia. Common procedures like joint replacements, Caesarean sections, organ transplants and chemotherapy could also become too risky to carry out.

The Bureau has tracked more than 2,800 tonnes of colistin for use on animals shipped to India, Vietnam, South Korea, Russia, Nepal, Guatemala, Colombia, Bolivia, Mexico and El Salvador in 2016. The total is likely to be higher as the product may be shipped under its brand name rather than being labelled as colistin - and to other countries for which customs data is not made public. By comparison, the UK uses less than a tonne a year of colistin in agriculture.

Colistin is manufactured by two companies in India but the country is also importing at least 150 tonnes of the drug each year.

India has been called the epicentre of the global drug resistance crisis. A combination of factors described as a “perfect storm” have come together to hasten the spread of superbugs. Unregulated sale of the drugs for human or animal use - accessed without prescription or diagnosis - has led to unchecked consumption and misuse. India has a large population, some of whom defecate in the open, and waste is often poured untreated into rivers and lakes. This creates the perfect conditions for bugs to share resistance.

Poor sanitation means people often catch infections that require treatment with antibiotics. Overuse of the drugs in hospitals has created antibiotic resistant hotspots, and poor infection control means these bugs spread within the hospital and into the community. Some of the pharmaceutical companies manufacturing antibiotics have also failed to dispose of antibiotic-ridden waste properly, fuelling the spread of resistant bugs in the environment.

All of these factors have led to high rates of resistance. In India 57 per cent of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteria - which commonly cause urine, lung and bloodstream infections - are resistant to last line antibiotics known as carbapenems. In the UK by comparison the figure is below one per cent. Doctors in some areas of India see patients with pan-resistant infections (immune to nearly all antibiotics) at least once a month. The government does not collect figures on how many people are dying of resistant infections but one study estimates drug-resistant infections kill 58,000 newborn babies in India every year.

Bugs bred in India spread globally. One which particularly worried scientists is a gene called New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase 1 (NDM-1), which makes bugs resistant to carbapenem antibiotics. This has been dubbed “the nightmare bacteria” by the Centers for Disease Prevention or Control in the US because it kills half the patients who develop a bloodstream infection.

NDM-1 was first found in a patient who acquired it in India in 2008 and has since spread all over the world, with over 1,100 laboratory confirmed cases in the UK since 2003. It is far from the only one being spread from India. The mcr-1 gene which confers colistin resistance spread round the world in three years. Some 11 per cent of travellers to India came home colonised with mcr-1 bacteria, a recent study found.

“You know this is preventable”

Dr Sanjeev Singh is a medical superintendent at The Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences in Kochi, India. He has to treat patients with multi-drug resistant infections up to three times a week and patients with pan-drug resistant infections (those immune to nearly all antibiotics) up to twice a month.

“The situation is grim. As a clinical practitioner it becomes extremely difficult to treat a patient with multidrug and pan drug resistant organisms. You feel helpless, despite being able to diagnose the patient, you are left with limited options. This increases the illness and mortality of the patients and cost of the care also shoots up. You have very limited options for treatment only because the rest of the people in the chain, which includes animal industry, policy makers, waste disposal people, have not played their role nicely.”

“You know this is preventable but you see these patients crashing in front of you and dying. If it is happening to a young person who could have been so productive, it pains you. All the people in the chain, if they don’t participate and work as a team, it’s going to be very very difficult.”

Indian poultry: growing fast

In India the poultry industry is booming. The amount of chicken produced doubled between 2003 and 2013. Chicken is popular because it can be eaten by people of all religions (pork is forbidden to Muslims and beef is prohibited to Hindus) and because it is versatile and inexpensive relative to other meats. The majority of poultry is now produced by commercial farms, contracted to major companies like Venky’s. Researchers who tested Indian meat from supermarkets in 2014 found it contained residues of six antibiotics, suggesting they were being used liberally on farms. (The Indian Ministry of Agriculture said the residues were well within the range allowed by other international agencies).

Experts predict the rising demand for protein will cause a surge in antibiotic use in livestock. India's consumption of antibiotics in chickens is predicted to rise fivefold by 2030 compared to 2010, while globally the amount used in animals is expected to rise by 53 per cent.

The World Health Organisation released guidelines in November 2017 recommending reducing use of critically important antibiotics in food-producing animals and banning their use as growth promoters. It also recommended banning the mass medicating of livestock with antibiotics to prevent disease.

Using antibiotics as growth promoters has been banned in the European Union since 2006, and in the US was made illegal in 2017.

In 2014 India’s ministry of agriculture sent an advisory letter to all state governments asking them to review the use of antibiotic growth promoters. However the directive was non-binding, and none have introduced legislation to date. In its National Action Plan on AMR published in 2017 the Indian government banned using antibiotics as growth promoters. The plan is not currently linked to any regulatory action.

Antibiotics as a substitute for hygiene

Indian farmers use antimicrobials as a substitute for good farming practices, according to Professor Ramanan Laxminarayan, director of the Centre for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy, based in Delhi.

“If you go to the average poultry farm in Punjab you see these are all lacking: the nutrition is not there, hygiene is awful. So they are using the antibiotics as a substitute of keeping the animals alive”, he said. The reason this is done is because antibiotics are cheap. “If the true cost was factored in - the cost of resistance - it wouldn’t seem like such a good option”, he added.

He believes consumer pressure rather than regulation is what will drive change. He points out that much of the poultry consumption in India is through direct sales to consumers rather than fast food chains.

“Consumers [in the West] were previously unaware their chicken was being raised on antibiotics and once they found out they didn’t want it”, he said. “In India that level of awareness doesn’t exist. I think it needs social change. It needs leaders, it needs stories, it needs organisation. It’s the same for tobacco, nobody smokes now indoors, nobody smokes around children. The level of awareness is further on than with antibiotics.”

Professor Walsh believes there is no time to waste for this change. “These resistant bugs aren’t waiting around, they are rapidly spreading”, he said. “The antibiotic pipeline is modest at best so we must act quickly to preserve our last-resort drugs. If we don’t act now by 2030 colistin will be dead as a drug. We will have serious drug resistant infections and nothing to use against them.”

The Times published a version of this piece, which you can view here: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/art...

The Hindu published a version of this piece, which you can view here: http://www.thehindu.com/news/n...