“A national scandal”: 449 people died homeless in the last year

A grandmother who made potted plant gardens in shop doorways, found dead in a car park. A 51-year-old man who killed himself the day before his temporary accommodation ran out. A man who was tipped into a bin lorry while he slept.

These tragic stories represent just a few of at least 449 people who the Bureau can today reveal have died while homeless in the UK in the last 12 months - more than one person per day.

After learning that no official body counted the number of homeless people who have died, we set out to record all such deaths over the course of one year. Working with local journalists, charities and grassroots outreach groups to gather as much information as possible, the Bureau has compiled a first-of-its-kind database which lists the names of the dead and more importantly, tells their stories.

The findings have sparked outrage amongst homeless charities, with one expert calling the work a “wake-up call to see homelessness as a national emergency”.

Our investigation has prompted the Office for National Statistics to start producing its own figure on homeless deaths.

We found out about the deaths of hundreds of people, some as young as 18 and some as old as 94. They included a former soldier, a quantum physicist, a travelling musician, a father of two who volunteered in his community, and a chatty Big Issue seller. The true figure is likely to be much higher.

Some were found in shop doorways in the height of summer, others in tents hidden in winter woodland. Some were sent, terminally ill, to dingy hostels, while others died in temporary accommodation or hospital beds. Some lay dead for hours, weeks or months before anyone found them. Three men's bodies were so badly decomposed by the time they were discovered that forensic testing was needed to identify them.

They died from violence, drug overdoses, illnesses, suicide and murder, among other reasons. One man’s body showed signs of prolonged starvation.

You can read the stories of all those who died here

"A national disgrace"

Charities and experts responded with shock at the Bureau’s findings. Howard Sinclair, St Mungo’s chief executive, said: “These figures are nothing short of a national scandal. These deaths are premature and entirely preventable.”

“This important investigation lays bare the true brutality of our housing crisis,” said Polly Neate, CEO of Shelter. “Rising levels of homelessness are a national disgrace, but it is utterly unforgivable that so many homeless people are dying unnoticed and unaccounted for.”

Our data shows homeless people are dying decades younger than the general population. The average age of the people whose deaths we recorded was 49 for men and 53 for women.

“We know that sleeping rough is dangerous, but this investigation reminds us it’s deadly,” said Jon Sparkes, chief executive of Crisis. “Those sleeping on our streets are exposed to everything from sub-zero temperatures, to violence and abuse, and fatal illnesses. They are 17 times more likely to be a victim of violence, twice as likely to die from infections, and nine times more likely to commit suicide.”

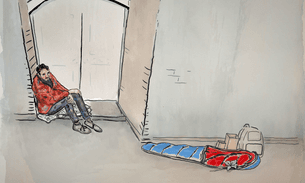

People's belongings and a tent in an underpass in Milton Keynes, May 2018

Photo by Alex Sturrock

People's belongings and a tent in an underpass in Milton Keynes, May 2018

Photo by Alex Sturrock

The Bureau’s Dying Homeless project has sparked widespread debate about the lack of data on homeless deaths.

Responding to our work, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) has now confirmed that it will start compiling and releasing its own official estimate - a huge step forward.

For months the ONS has been analysing and cross-checking the Bureau’s database to create its own methodology for estimating homeless deaths, and plans to produce first-of-their-kind statistics in December this year.

A spokesperson said the information provided by the Bureau "helps us develop the most accurate method of identifying all the deaths that should be counted."

Naming the dead

Tracking homeless deaths is a complex task. Homeless people die in many different circumstances in many different places, and the fact they don’t have a home is not recorded on death certificates, even if it is a contributing factor.

There are also different definitions of homelessness. We used the same definition as that used by homeless charity Crisis; it defines someone as homeless if they are sleeping rough, or in emergency or temporary accommodation such as hostels and B&Bs, or sofa-surfing. In Northern Ireland, we were only able to count the deaths of people registered as officially homeless by the Housing Executive, most of whom were in temporary accommodation while they waited to be housed.

For the past nine months we have attended funerals, interviewed family members, collected coroners’ reports, spoken to doctors, shadowed homeless outreach teams, contacted soup kitchens and hostels and compiled scores of Freedom of Information requests. We have scoured local press reports and collaborated with our Bureau Local network of regional journalists across the country. In Northern Ireland we worked with The Detail's independent journalism team to find deaths there.

Of the 449 deaths in our database, we are able to publicly identify 138 people (we withheld the identity of dozens more at the request of those that knew them).

Of the cases in which we were able to find out where people died, more than half of the deaths happened on the streets.

These included mother-of-five Jayne Simpson, who died in the doorway of a highstreet bank in Stafford during the heatwave of early July. In the wake of her death the local charity that had been working with her, House of Bread, started a campaign called “Everyone knows a Jayne”, to try to raise awareness of how easy it is to fall into homelessness.

Forty-one-year-old Jean Louis Du Plessis also died on the streets in Bristol. He was found in his sleeping bag during the freezing weather conditions of Storm Eleanor. At his inquest the coroner found he had been in a state of “prolonged starvation”.

Russell Lane was sleeping in an industrial bin wrapped in an old carpet when it was tipped into a rubbish truck in Rochester in January. He suffered serious leg and hip injuries and died nine days later in hospital. He was 48 years old.

In other cases people died while in temporary accommodation, waiting for a permanent place to call home. Those included 30-year-old John Smith who was found dead on Christmas Day, in a hostel in Chester.

Or James Abbott who killed himself in a hotel in Croydon in October, the day before his stay in temporary accommodation was due to run out. A report from Lambeth Clinical Commissioning Group said: “He [Mr Abbott] said his primary need was accommodation and if this was provided he would not have an inclination to end his life.” We logged two other suicides amongst the deaths in the database.

Many more homeless people were likely to have died unrecorded in hospitals, according to Alex Bax, CEO of Pathways, a homeless charity that works inside several hospitals across England. “Deaths on the street are only one part of the picture,” he said. “Many homeless people also die in hospital and with the right broad response these deaths could be prevented.”

Rising levels of homelessness

The number of people sleeping rough has doubled in England and Wales in the last five years, according to the latest figures, while the number of people classed as officially homeless has risen by 8%.

In Scotland the number of people applying to be classed as homeless rose last year for the first time in nine years. In Northern Ireland the number of homeless people rose by a third between 2012 and 2017.

Analysis of government figures also shows the number of people housed in bed and breakfast hotels in England and Wales increased by a third between 2012 and 2018, with the number of children and pregnant women in B&Bs and hostels rising by more than half.

“Unstable and expensive private renting, crippling welfare cuts and a severe lack of social housing have created this crisis,” said Shelter's Neate. “To prevent more people from having to experience the trauma of homelessness, the government must ensure housing benefit is enough to cover the cost of rents, and urgently ramp up its efforts to build many more social homes.”

The sheer scale of people dying due to poverty and homelessness was horrifying, said Crisis chief executive Sparkes.“This is a wake-up call to see homelessness as a national emergency,” he said.

A homeless person heats food over a fire in an underpass in Milton Keynes, May 2018

Photo by Alex Sturrock

A homeless person heats food over a fire in an underpass in Milton Keynes, May 2018

Photo by Alex Sturrock

Breaking down the data

Across our dataset, 69% of those that died were men and 21% were women (for the remaining 10% we did not have their gender).

For those we could identify, their ages ranged between 18 and 94.

At least nine of the deaths we recorded over the year were due to violence, including several deaths which were later confirmed to be murders.

Over 250 were in England and Wales, in part because systems to count in London are better developed than elsewhere in the UK.

London was the location of at least 109 deaths. The capital has the highest recorded rough sleeper count in England, according to official statistics, and information on the well-being of those living homeless is held in a centralised system called CHAIN. This allowed us to easily record many of the deaths in the capital although we heard of many others deaths in London that weren’t part of the CHAIN data.

In Scotland, we found details of 42 people who died in Scotland in the last year, but this is likely a big underestimate. Many of the deaths we registered happened in Edinburgh, while others were logged from Glasgow, the Shetland Islands and the Outer Hebrides.

Working with The Detail in Northern Ireland, we found details of 149 people who died in the country. Most died while waiting to be housed by the country’s Housing Executive - some may have been in leased accommodation while they waited, but they were officially classed as homeless.

“Not only will 449 families or significant others have to cope with their loss, they will have to face the injustice that their loved one was forced to live the last days of their life without the dignity of a decent roof over their head, and a basic safety net that might have prevented their death," Sparkes from Crisis. No one deserves this.”

A spokesperson from the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said:

“Every death of someone sleeping rough on our streets is one too many and we take this matter extremely seriously.

“We are investing £1.2bn to tackle all forms of homelessness, and have set out bold plans backed by £100m in funding to halve rough sleeping by 2022 and end it by 2027."

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

Additional reporting by Rory Winters of The Detail who uncovered the data from Northern Ireland.