Nowhere to turn: Women say domestic abuse by police officers goes unpunished

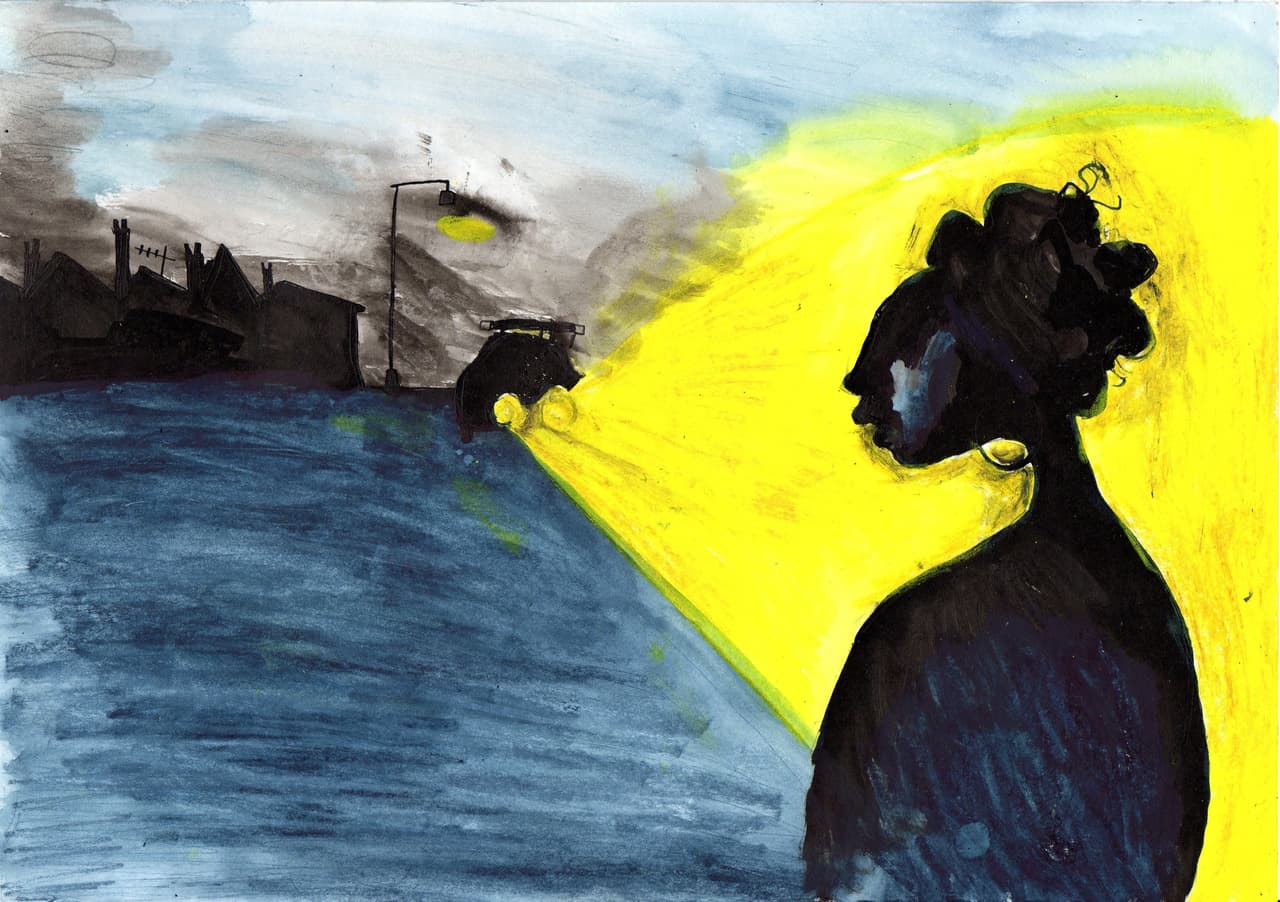

One late summer evening, Debbie cracked. After weeks of deliberating, she phoned Merseyside Police to report her partner for serious allegations of physical and verbal abuse. It was a decision she would soon regret. The problem, she says, is that he was an officer with the same force.

“He used to say the police would protect him and if I phoned up against him, he’d just get me put in prison,” she said. “One day it was too much and I did phone. In hindsight that was the biggest mistake of my whole life.”

Domestic abuse is often predicated on fear. Fear of what your abuser will do next, fear that you're going mad, fear that no one will believe you. Many of those affected are understandably afraid of how their partner will react if they report them; some do so anyway.

So what happens when your abuser is part of the system that's supposed to protect you?

Debbie is one of multiple women who have told the Bureau of Investigative Journalism they suffered emotional or physical abuse at the hands of police officer partners, and that they believe their partners used their professional positions to seek to intimidate or harass them.

From across the country we heard claims that alleged abusers got their partners repeatedly arrested, stalked them in marked cars, or warned them there was no point going to the police because the force was "a family."

Some were too scared to ever report it. For those that did go to the police, the experience only served to traumatise them further, they say. They feel their partners’ colleagues failed to adequately follow up on serious allegations and that they were discouraged from making statements. Some complained about their treatment but the complaints were not upheld.

What had happened to these women was “sickening,” said Shadow Policing Minister Louise Haigh. But their stories may be pieces of a bigger picture, our investigation suggests.

Police officers and staff across the UK were reported for alleged domestic abuse almost 700 times in the three years up to April 2018, according to Freedom of Information responses - more than four times a week on average. The real figure is likely to be much higher as data was only provided by 37 of the UK’s 48 police forces (including specialist forces).

Beyond the number of allegations, the figures suggest reports about alleged abuse by police are treated differently. Just 3.9% in England and Wales ended in a conviction, compared with 6.2% among the general population. Less than a quarter of reports resulted in any sort of professional discipline. Greater Manchester Police, one of the country’s biggest forces, secured just one conviction out of 79 reports over the three year period.

Lawyers, MPs, campaigners and a police and crime commissioner said changes must be made to police procedures. “We are shocked by the findings," said Lucy Hadley, campaigns and public affairs manager at Women’s Aid. "No one should be above the law (...) Police leaders must take urgent action to ensure that all forces have the appropriate procedures in place so that survivors are protected and can access justice whatever their abuser’s profession.”

The women we spoke to, alongside experts and advocates, say provisions must be put in place to ensure victims feel safe to go to the police when their abuser is a police officer, and that their complaints are seen to be treated exactly the same as those made by any other person.

One proposed measure is requiring another force to carry out the investigation. Haigh, the shadow policing minister, wants to go even further: she believes all allegations of police misconduct should be investigated completely independently of the police.

Less than a third of the forces that responded to the Bureau’s FOI requests have specific procedures in place to ensure an impartial response when their employees are accused of domestic abuse. Some appoint an investigating officer not known to the accused or take the suspect to a different station from the one where they usually work - but many have no provisions in place at all.

"One of ours"

On the night Debbie phoned the police, four male officers came to her house. She told them her partner had warned her of police loyalty, and she repeatedly said she felt intimidated, but none of them left her living room.

She told them about a particularly nasty row a few weeks earlier when, she claims, the abuse turned physical. She threw some water at him from a bottle, then he grabbed her by the neck and pulled her along the floor, she alleged.

She was shocked by what one of the officers said next. “He told me: ‘So we have two assaults here - one for each of you. Then he said: ‘Are you looking to report that?’”

Debbie’s lawyer believes the officer chose his words deliberately to make a point. “It is understandable that my client felt that she was being discouraged from [reporting the assault], even if indirectly,” said the lawyer.

Debbie feels the police acted differently because her partner was a fellow officer. “I never got treated like the victim. If he’d been a butcher who’d hit me or a traffic warden or a solicitor, they would not have been the way they were with me,” she said.

She later complained to Merseyside Police, and the force completed an internal misconduct investigation in 2017. The resulting report said: “It could be argued that the officers have treated [Debbie] fairly and equally by explaining that she may have committed an offence so that she was aware of the potential repercussions.” It dismissed Debbie’s complaint, apart from acknowledging that one officer failed to let her know about her legal rights.

A retired detective superintendent with extensive experience of domestic abuse cases told the Bureau throwing water was not usually treated as an assault. Grabbing someone around the throat, however, is considered a “high risk” indicator of potentially more serious future abuse.

Kay Neve, a former detective constable with Kent Police who spent three years working on police misconduct cases, said that while throwing water could technically be an assault, the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) would be unlikely to prosecute. “[The] two actions are at opposite scales of the spectrum and I would expect an experienced officer to be able to put that in context,” she said.

Debbie did choose to give a statement about her partner’s alleged assault that night, and he was arrested and placed on pre-charge bail. Soon after he breached his bail conditions by contacting her and leaving voicemails. She reported this, but the investigating officer did not visit her to collect the voicemails for two weeks, by which time she says some messages had been deleted.

This delay was “not acceptable”, said Neve. Breach of bail and voicemail messages was something that should always be followed up on in alleged domestic abuse cases, she said, because of what could potentially happen next.

There is no indication in Merseyside’s misconduct report that Debbie's partner was internally disciplined for breaching bail conditions, and the CPS decided not to charge for the alleged assault.

“I would have expected some consequences as a result of breaching bail because [as] police officers, you have to abide by the laws, rules, regulations,” said Neve. “It’s not one rule for a police officer and one rule for somebody else.”

Debbie’s ex-partner has since been dismissed on an unrelated matter. When we asked the force to respond to our findings, it said it would be inappropriate to comment on Debbie’s case.

“Although the police denied they were protecting him, I can’t help but feel they were because he’s had no sort of recriminations whatsoever - about breaching bail, about anything he did to me,” said Debbie. “Merseyside Police say they have zero tolerance for domestic abuse, but they really should have a bracket under that saying, ‘Except if it’s one of ours.’”

Suffering compounded

Suzanne feels she has been failed by another police force multiple times after suffering years of abuse by her officer husband. Her experience and her inability to get justice has affected her so badly, she said, that it has contributed to her attempting suicide multiple times.

The alleged abuse took place in the 1990s. It began when he pushed her in front of a car while pregnant, she said, and continued for years. When she filed for divorce, she says he raped her.

She reported the alleged rape but later felt too vulnerable to support an investigation. She says officers dealing with it promised her the report would be kept on file. But in 2012, when she needed the incident’s crime number to access criminal injuries compensation for mental health treatment, the police said they had no record of it.

“I felt violated all over again. For over 10 years I’d held on to the fact that was on file. That had helped me cope with it, the fact it was there,” said Suzanne. “Then to suddenly find out it wasn’t there at all, it shakes your reality… I had a breakdown because of that.”

She made an official complaint in 2015 but the force dismissed it, saying any record of the report would have been destroyed according to protocols. She later appealed to the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), which agreed the force’s investigation into her 2015 complaint had been inadequate.

The force had failed to fully check if any records of Suzanne’s alleged rape existed, the IOPC found, and it had not contacted the officers she said had dealt with her case.

It was not just the alleged rape the police failed to deal with properly, Suzanne claims. She says that after her divorce, a teacher saw her ex-husband pushing their son into a car. The police spoke to the boy, and Suzanne later saw a video of that interview.

“I could see my son swinging his legs, he was so little his feet didn’t even reach the floor, and he’s in his school uniform,” she said. “He said his father tried to strangle him and had his hands on his throat. The other one was that he tried to suffocate him.”

Officers did not follow up on the boy’s allegations, Suzanne says. When she complained about this alongside the lost rape report, the grievance was also dismissed by the force. And again, the appeal to the IOPC found in her favour. The force had not attempted to speak to the officers who had interviewed her child at the time, said the IOPC, and it had not tried to trace any records that might explain why no prosecution was pursued.

“I know for a lot of victims it feels like they don’t matter, but I felt I mattered even less than other victims, because I was a police victim,” Suzanne said. “It felt like gaslighting, I suppose. I felt I had nowhere to go.”

The IOPC ordered the force to re-investigate Suzanne’s case in January 2018, but last week the force responded saying it could not uphold the majority of her complaints.

Suzanne’s lawyer, the prominent women’s rights solicitor Harriet Wistrich, has serious concerns about the lost rape report. “The fact that seems to have just gone missing, particularly in the circumstances where [Suzanne] was given massive assurances… It’s very concerning,” she said. “It leaves a sense of suspicion that it’s because he’s a police officer that they’ve conveniently lost that information.”

Wistrich successfully acted against the Metropolitan Police for eight women who had relationships with undercover officers who had infiltrated activist groups, as well as two victims of the “black cab rapist,” John Worboys. People should not assume stories like Suzanne’s were out of the ordinary, she warned.

“We’ve heard of these cases again and again,” she said. “It’s about police culture and about believing and supporting your colleagues over and above the fact they may be dangerous and acting in a criminal manner.”

Inside knowledge

Both men and women who experience domestic abuse speak of the fear of reporting - of not being believed, of what your abuser might do, of being judged. Just 28% of women using community-based domestic abuse services and 44% of those in refuges had reported their experiences to the police when Women’s Aid performed a survey in 2017.

If your abuser is a police officer, those fears take on a whole new dimension, our investigation suggests. All the women we spoke to said the fact their partner served with their local force meant they were terrified to report them.

While Debbie and Suzanne did ultimately make reports, we spoke to several other women around the country who say they were simply too scared.

Amy said her controlling officer boyfriend would threaten to deploy criminals he had met on the job to harm her and his ex-wife. She never reported him and she keeps in touch with him, for fear of what he will do if she doesn’t.

“He told me, ‘I know people, if I want her legs broken, it’s £5,000 and if I want her done away with so there’s no trace at all of her, it’s £10,000,’” she said. “Quite often if we had arguments, he’d look at me and say, ‘You do realise I don’t have to hurt anybody...’”

Danielle, who says she suffered years of physical abuse from her officer husband, and that he later raped her, told the Bureau she felt completely helpless. “He would always say, ‘Look at the job I do, who’s going to believe you? There’s lots of us,’” she said. “At the point where you have no confidence left and you have nobody, you think, ‘The people I need to go and tell, I can’t go and tell them because he’s one of them.’”

Her husband would use his knowledge of legal processes as part of the intimidation, she claimed. “If I tried to talk to him about his behaviour, he’d sit and record me and say, ‘Well, I’ll just use that in court against you.’” The Bureau has evidence showing an officer in another force withheld information from fellow officers and from courts in order to obtain injunctions against his ex-wife and get her repeatedly arrested.

Other women told us of their partners keeping notes or making diary entries that painted them as the aggressors. Another former special constable said a colleague of hers used to repeatedly stalk his ex-girlfriend in a marked car while they were on duty.

Suzanne claimed officers from her ex-husband’s force attempted to intimidate her after her divorce by repeatedly stopping her new boyfriend in his car. “He was stopped so many times by the police, them trying to get him for speeding or whatever, that he ended up going to the station saying he was going to make an official complaint if they didn’t stop harassing him because he was dating a police officer’s ex,” she said.

Calls for change

One police and crime commissioner believes the women’s fears of police loyalty may be justified. Dame Vera Baird QC, a former solicitor general for England and Wales, was elected to oversee Northumbria Police in 2012 and is now the national police and crime commissioner lead on domestic abuse.

“I’m not surprised that these issues don’t appear to be taken as seriously as they should by the police,” she told the Bureau. “There is a sort of defensive, rather collective, together, mutually supportive culture” among police officers, she said, which can make “forces and probably some individual officers quite resistant to hearing about wrongdoing in colleagues.”

Baird, alongside leading domestic abuse charities, lawyers and MPs, said the Bureau’s findings highlighted an urgent need for reform. She said she would look at setting up a partnership between Northumbria and its neighbouring forces to deal with incidents in which a police officer is accused of domestic abuse. Such a partnership would see the local force responding to emergency incidents, she said, but any criminal investigations would be handed over to the neighbouring force to carry out.

Such a system should be mandatory in most cases, argued Baird. “[This] is about justice being seen to be done,” she said.

Only three police forces in the country do anything like this, according to our FOI responses. Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire police forces have a joint policy which recommends that if an officer in one force is accused of domestic abuse, one of the neighbouring two forces should undertake the investigation “in some serious or sensitive cases.”

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

Shadow policing minister Louise Haigh, and Debbie and Suzanne’s solicitors, think all forces should adopt a similar policy, and that the IOPC should automatically oversee investigations if a police officer is accused of domestic or sexual abuse. Haigh went even further to suggest that “any allegations of police misconduct are investigated entirely independently of the police, and that includes neighbouring forces.”

MP Thangam Debbonaire, who chairs the all-party parliamentary group on perpetrators of domestic abuse and worked in the sector for more than two decades, believes the involvement of another force in cases where police officers are accused should be the “bare minimum.”

“It takes a phenomenal amount of guts to raise a complaint against a police officer,” she said, adding it was natural that a victim would not trust her abuser’s colleagues.

As well as changes in how allegations of abuse against police officers are investigated, changes should be made to give victims a safe way to report it, say leading charities. The option to report the crime to a force where their partner doesn’t work, or to someone very senior within their partner’s force, could make a big difference, said Lucy Hadley, national campaigns and public affairs manager at Women’s Aid. Mary Mason, chief executive of Solace Women’s Aid in London, suggested an independent police unit could be set up to investigate police officers accused of crimes, with its own telephone hotline.

Danielle said such measures would have encouraged her to report her husband. “If I’d known there were other places I could go to, then yeah I would do that, because if it’s somebody else investigating, you would feel you do actually have some backing,” she said.

Responding to the Bureau’s findings, the National Police Chief Council (NPCC) and College for Policing said measures already existed to make sure abuse perpetrated by police officers was properly investigated.

Chief Constable Martin Jelley, the NPCC’s lead for ethics and integrity, said: “I am confident that we have robust procedures in place to deal with the small number of officers who break the law, including criminal convictions and ultimately dismissal.”

No one should live in fear of domestic abuse, said Jelley, urging victims to come forward. “Domestic abuse is a very serious crime that can have a devastating impact on victims and we take all allegations of it seriously.”

The College of Policing said their official guidance on police-involved domestic abuse made it clear “that police officers who commit domestic abuse-related offences should not be treated differently to any other suspect and recommends considering involving another force in investigations in appropriate cases.”

In fact, the guidance suggests only that police “could consider establishing mutual arrangements with another force for the provision of anonymous help and information” when an alleged perpetrator is a police officer. The Home Office told the Bureau it was implementing “a wide-ranging programme of reforms to improve police integrity, including improving the transparency of the disciplinary system and strengthening the powers of the IOPC.”

Looking back

Several years after the night she first called the police, Debbie is still furious about what happened next. Looking back at her experience with Merseyside Police, she feels “betrayed, belittled and completely disillusioned,” she said.

Both she and Suzanne now plan to sue the police for what they see as a failure to protect them and deliver justice. Debbie is struggling to access legal aid, but is determined to pursue her case on behalf of others who may be suffering, not knowing where to turn.

“Nobody has ever said we didn't treat you right in this circumstance,” she said. “I've never had any sort of apology from the police. Nothing. I just would like to see this never happen to another woman in the future.”

Suzanne said it terrified her to think anyone could hurt her and she couldn’t go to the police for help, because she doesn’t trust them. “Who am I meant to go to?,” she said.

She wants one message to be heard by all the police officers who dealt with her case over many years.

“You're paid to protect me, like all of the public, but you chose to protect my abuser,” she said. “I need to see you stand up for victims like me. Stand up against injustice and do the right thing.”

*We spoke to women in six different police force areas for this story. The names of Debbie, Suzanne, Danielle and Amy have been changed, and none of the forces named apart from Merseyside, for legal reasons.

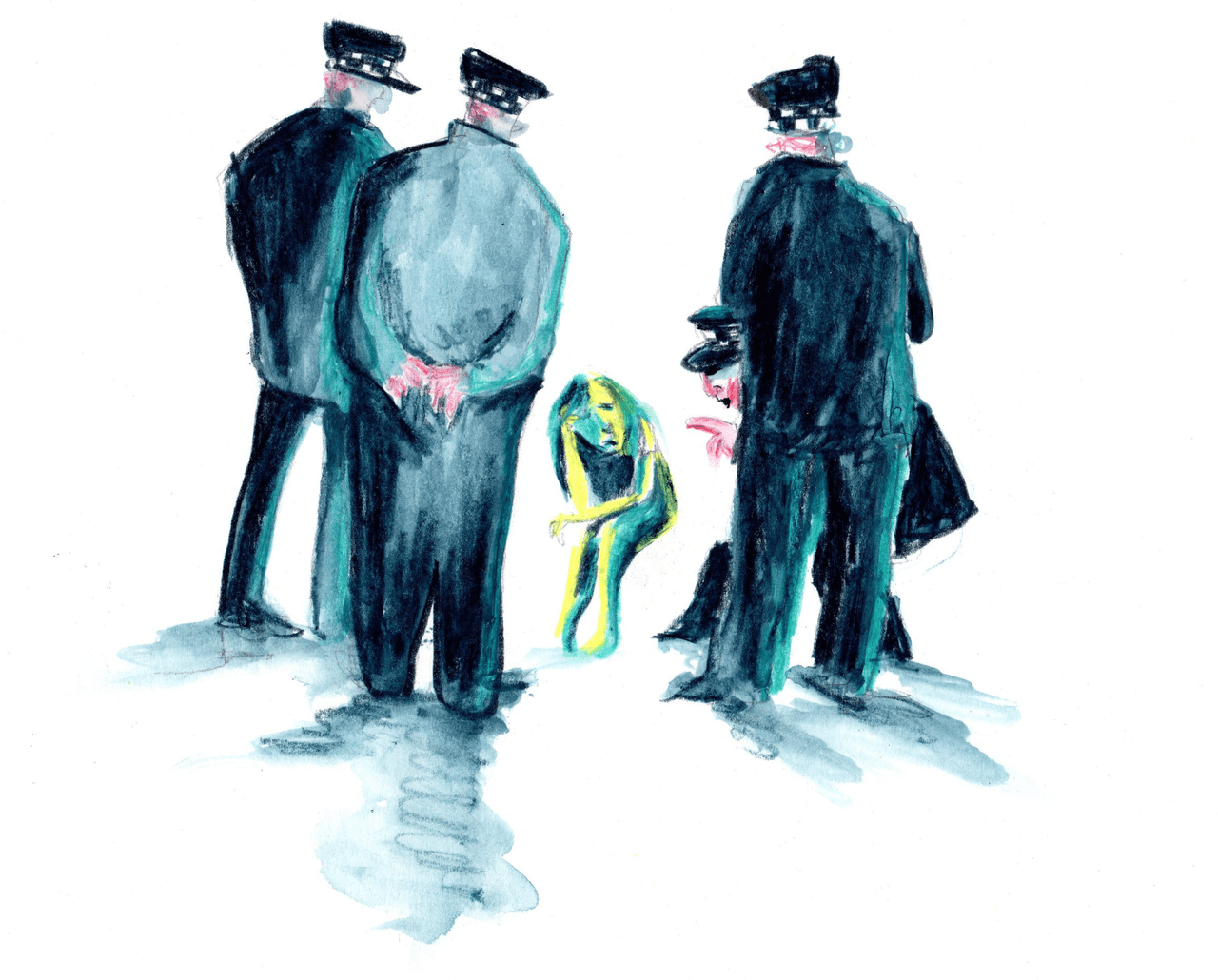

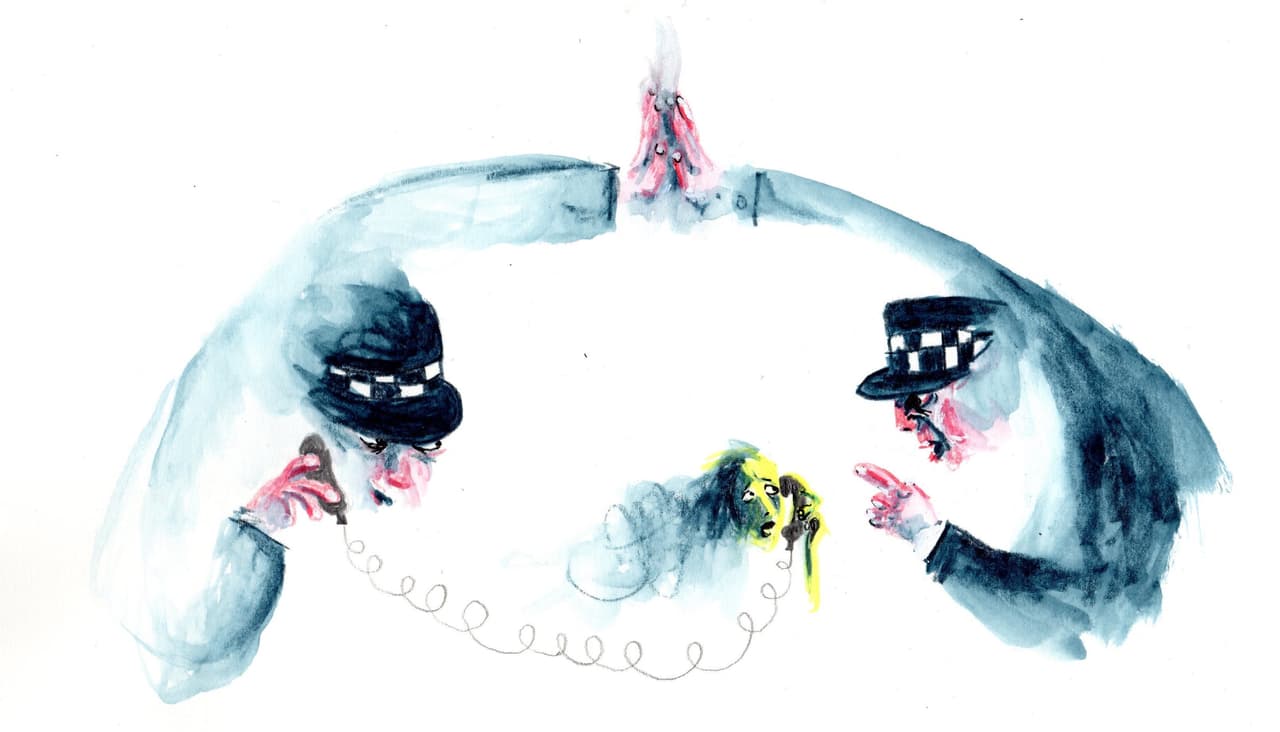

All illustrations by Danny Noble

Our reporting on domestic violence is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.