Revealed: Thousands of care jobs pay below living wage despite promises

Home care workers across Britain are working for less than the real living wage, despite many councils pledging to pay at least that much, according to new research by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

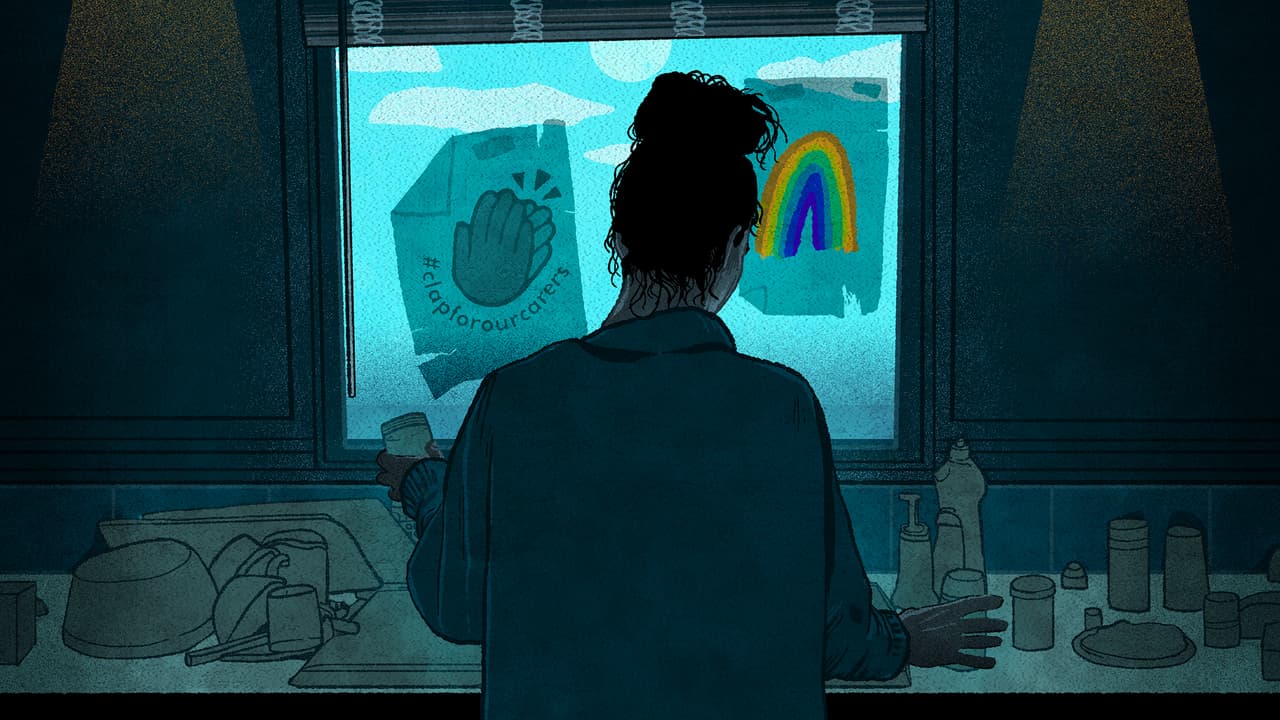

Long-awaited plans to reform adult social care have failed to materialise, while the pandemic has piled more pressure on the system. The government has no clear plan as to how to address a huge funding gap – estimated at £10bn – but has encouraged the public to Clap For Our Carers, a response one care worker called pathetic.

According to polling by the Fawcett Society, most people in the UK think that home carers should get the real living wage – an amount meant to cover bills and costs of living with some money to set aside for emergencies, such as urgent dental work. Yet the Bureau can reveal that more than 60% of care worker jobs advertised in the past six months were paid less than that - a figure that amounts to more than 7,000 jobs across Britain.

The rate was even higher in Wales, where nearly three quarters of all care worker jobs were below the real living wage, despite the fact that the Welsh government recently pledged that all care workers would be paid that rate.

Most home care is paid for at least in part by local councils, and 43 local authorities have signed up to a charter pledging to pay their care workers the real living wage. But the Bureau found jobs advertised for less than that in 37 of those areas, with some offering as little as £8 an hour, less than minimum wage for those over 21.

Care workers said low pay for gruelling work had left many of them struggling to feed and clothe their families, brought on mental and physical health issues, and made many of them consider leaving their jobs. One care worker told the Bureau: “The only way to cover your living costs in this profession is by sacrificing your own health and your family to work ridiculous hours.”

Responding to our findings, the health minister Sajid Javid said: “Our carers have done an absolutely remarkable job, especially during this pandemic ... I would like to see a fairer settlement for carers, and that is part of our plan on social care to have a more long-term sustainable solution.” However, when pushed he would not say how the necessary additional funding would be found.

Angela Rayner, Labour’s deputy leader who was herself a care worker before becoming an MP, said: “It is a national disgrace that the vast majority of social care workers are being paid less than the living wage ... The prime minister promised us a plan to fix social care. He needs to put his money where his mouth is and start treating our social care heroes with the dignity and respect that they deserve.”

Home care workers provide vital support for millions of people including those with physical disabilities, learning difficulties, chronic illnesses or the elderly. Their role can include the most intimate of tasks, such as helping people to get washed, dressed, fed, medicated and go to the toilet. For some people, their care workers are the only human contact they will have in a day.

The Bureau analysed thousands of job advertisements scraped from Reed.co.uk, one of the UK’s biggest recruitment websites, over six months, and compiled a list of home care providers used by councils through Freedom of Information requests and public spending records. Comparing the two gave a data set of all the jobs advertised by care providers known to be providing council-commissioned care.

While it was impossible to determine if each job was paid for by a council or a private client, several of these care companies told the Bureau that no care worker’s job would be purely public or private care, and that the majority of their work came from councils. This tallies with research that suggests about three quarters of all home care is publicly funded.

Get involved

Want to investigate this story in your area? Use our reporting recipe to dig into the local data

Yes! I want to helpThe demand for home care services has seen a “phenomenal” increase during the pandemic and experts warn the effects of long Covid might cause additional strain. New research from the Royal Society for Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA), shared exclusively with the Bureau, found social and care workers were severely affected by their workload and money worries during the pandemic, even compared to other key workers.

It is not a sudden crisis. Adult social care budgets across numerous councils have been under strain for years and Westminster funding has not met rising demand and costs. The Bureau’s analysis of council paperwork revealed that many would need millions of pounds more to be able to pay carers a real living wage.

“I love my job… but I’ll have to leave”

Justina* visits about a dozen elderly and people with mental health issues every day. She earns £9.20 an hour, less than the real living wage, which is set at £9.50 an hour for those outside London. The vast majority of the people she looks after have their care funded by the local authority. Her client list used to be split between three people, but now is covered by two, meaning she sometimes has to cut visits to vulnerable people short to fit everyone in.

She told the Bureau that watching people clap for carers while she struggled had frustrated her. “It was absolutely pathetic. I love my job but I told my boss if anything else comes up I’ll have to leave, because it is just so unappreciated … I’d go and sort packages if I have to. At one point I was working three jobs.”

A single mother, Justina said she struggled to afford clothes for her two children, let alone a tablet or computer, which caused problems when lockdown forced schools to close. She had to wake up at 4am to access her childrens’ set classwork on her mobile before copying it out by hand onto paper for them - all before setting off for a shift that could be up to 15 hours long.

She was recently injured on the job but, because her work has no occupational sick pay, her family has to survive on £96.35 a week. It is dire enough that she has been tempted to return to work, even if it means exacerbating her injury. “I was only thinking about the money that I would lose. You know, I wouldn't care if I became crippled for the rest of my life if there is money coming into my bank account,” she said.

Justina is not the only one for whom care work has taken a heavy toll. One home care worker told the Bureau that the stresses of the job meant many of her colleagues were on antidepressants. Another said the long hours and low pay had left her struggling with exhaustion, anxiety and depression. A survey by the RSA found that about a quarter of care workers felt they could not take time off work, even when sick.

Others feel systematically undervalued, including when it comes to costs incurred on the job. Emma*, a care worker in Hull, said that about a quarter of her take-home pay goes on petrol. “You’re never in one area. A few years ago we asked about money for petrol, [the care provider] replied by saying that was what the extra 0.30p was for in our hourly pay. It’s so disheartening.“

While care providers are supposed to pay workers for the time it takes them to travel between appointments, many still do not. Some workers told the Bureau that they had to end appointments early to allow time to travel, and had their pay cut as a result.

Laura Mwamba, the director of Be Caring, a home care agency, said the rate paid by councils made it impossible to offer a living wage. Councils across the north of England pay Be Caring for each hour of care needed, but she said they do not factor in travel time in between calls, nor the company’s other costs of doing business. “The hourly rate that we get paid does not cover the cost, so we cannot, we just physically cannot pay carers a living wage, and we can’t pay them from the time they’re out to the time they finish. We need better funding coming into the system so that we can pay people properly,” Mwamba said.

Promises unfulfilled

Justina works for a care provider commissioned by Cumbria council. That same council signed up to Unison’s Ethical Care charter, promising that all commissioned care work should be paid at the real living wage. Another 42 councils also signed the pledge, but the Bureau found home care worker ads offering below the living wage in 37 of them.

Although councils fund the majority of home care, they do not pay care workers directly. Instead they pay to commission the care from one of thousands of care providers, who in turn pay their staff. The UK Homecare Association (UKHCA) argues that the amount passed on to care providers is seldom enough to allow them to pass on real living wage. This was backed up by the Bureau’s analysis, which found that the vast majority (94%) of English councils were not paying a high enough average hourly rate to fund a real living wage.

Colin Angel, policy director at the UKHCA told the Bureau: “Councils’ claims to reward the workforce with the real living wage without offering fees or terms to match are empty promises and pointless publicity stunts.” He argued that more funding was needed from Westminster and that councils should be consulting more closely with care providers.

A spokesperson from Cumbria council said: “We will continue to encourage providers to pay the real living wage where they do not already, but we have no legal powers to make them do so.”

That response was echoed by many of the other councils who are signatories to the Unison charter. Some said they could not force providers to pay a certain amount, while one council conceded that ads had gone out with the wrong pay level. The pay rates were changed following queries from the Bureau.

Four signatory councils said their contracts required their care providers to pay at least the real living wage and some suggested ads found by the Bureau must be for private clients. However, the providers said they did not list roles separately and anyone applying for a position could be working with council-funded or private clients, or both.

The Unison general secretary Christina McAnea told the Bureau: “If some councils don't appear to be meeting their charter commitments, we will investigate and try to iron out what's been going wrong.”

Though some fell short, these 43 councils have at least recognised the need to pay home care workers a fair wage. Many others have done nothing to address the issue.

Andy Burnham, the mayor of Greater Manchester, expressed his support for care workers recently, tweeting: “The way our country treats care workers is disgraceful” and that they deserved a “massive pay rise.” Burnham has also said he wants all workers in Manchester to be paid the real living wage.

But while Manchester city council had previously committed to pay home care workers the real living wage, the Bureau found 20 ads from care providers used by the council which were offering less than that.

The council told the Bureau that it had “contractually committed” home care providers to pay the living wage. However, a recent budget noted that the council would need another £2m to be able to maintain this level of pay.

McAnea said: "Social care is a deeply flawed system in urgent need of reform. The blame for all that is wrong must be laid solely at the government’s door. Ministers have failed to fund the system or make the necessary reform and so now care is in the grip of a damaging crisis.

“With the sector starved of resources, many councils are forced to commission care at bargain basement rates, resulting in poverty pay for highly skilled and dedicated staff.”

A Deliveroo-style system

Beyond the impact on workers’ lives, low pay can also affect the quality of care provided to vulnerable people in need, with workers burning out and leaving the profession quickly. In some areas turnover rates are as high as 75% and up to one in three jobs is vacant. That leaves care users relying on an ever-changing rota of people for some of the most intimate care imaginable.

John* has seen the impact on the quality of care his mother receives. She lives in London and has multiple sclerosis (MS), schizophrenia and learning disabilities. “There’s always a different carer or there are shortages ... There’s a Deliveroo-style system of carers who are shipped to our house,” he said. “They’re on minimal wages, they work ridiculous hours for the pay they have – and they’re not given the time to do a good job.

“We have very good cause to believe that if we didn’t show up every once in a while, ideally probably every day, loads of really important things in mum’s care would slip,” he added. “It can all go down the drain because of scheduling issues.”

Carol Thompson, a care worker in Lancashire, told the Bureau that low pay meant many of those with experience were leaving the sector, and companies were finding it hard to recruit replacements.

“Staff are starting to look at the situation and thinking ... you might as well be working in a supermarket. You get paid more, with no responsibilities. I care for three adults with learning disabilities … and I’m responsible for them in all ways. It’s okay for us to have all these responsibilities, but they’re not recognising it in the pay,” she said. Carol is also paid under the living wage, at £8.91 an hour.

Earlier this year, the Bureau revealed that more than 25,000 people had died in the past year while receiving home care in England, and almost 3,000 died over that period in Scotland.

In recent months there have been repeated warnings about the growing crisis in adult social care. Leaders from eight major social care organisations wrote to the prime minister saying immediate funding was needed to avoid “serious risks”.

That sentiment was echoed in a report produced last month by the Commons’ Public Accounts Committee which found that “funding cuts have meant that most local authorities pay providers below the costs of care. This has led to many providers living hand-to-mouth, unable to make long-term decisions which would improve care services.”

Care workers, the committee said, “deserve better treatment”, and the health department needed to tackle low pay.

Since then a health secretary has resigned, and another has taken his place. In his first address to the Commons since taking up the role, Sajid Javid barely mentioned social care, only promising when questioned to stick to the plan for reform laid out by Matt Hancock. Until those long-promised reforms arrive, care workers up and down the country are stuck doing life-saving work for unlivable pay.

*Names have been changed

Reporters: Maeve McClenaghan, Charles Boutaud and Vicky Gayle

Paid working group: This story was inspired by ideas submitted to our Is Work Working call out and was investigated alongside freelance journalists Rosie Goodman, Jennifer Barton Packer and Nick Dowson.

Desk editor: Emily Wilson

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Collaborations: Shirish Kulkarni

Community Organising: Eve Livingston

Illustrations: Rebecca Hendin

Our reporting on jobs is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

Header illustration: A care worker washes up at a kitchen window. A Clap for Carers sticker is peeling off the window pane.

Graphics made via Flourish

-

Area:

-

Subject: