Financing fake news: Nike and Amazon advertise on Covid conspiracy sites

Dozens of the world’s biggest brands, including Nike, Amazon and Ted Baker, have been advertising on websites spreading Covid misinformation, such as claims that powerful people secretly engineered the pandemic and vaccines have caused thousands of deaths, the Bureau can reveal.

Ads for Amazon services were found on more than 30 sites that carried fake news ranging from Covid-19 conspiracy theories involving Bill Gates to claims that mRNA vaccines are “toxic”.

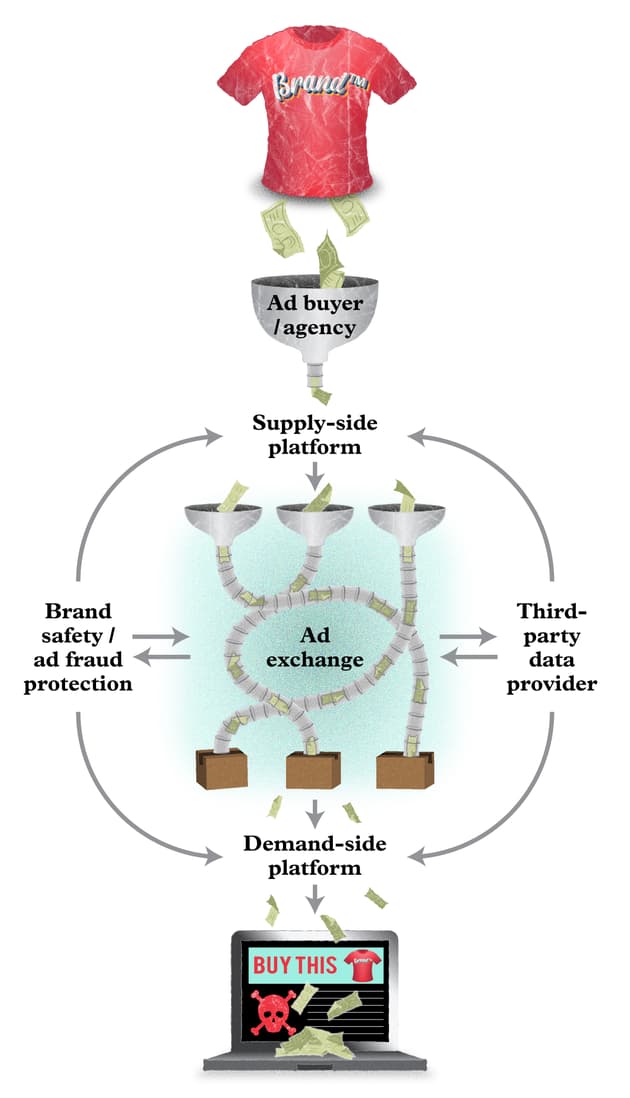

The Bureau’s analysis over a three-month period found ads for well-known consumer brands being channelled to almost 60 misinformation websites. These ads are placed through the “opaque by design” digital advertising market, which is expected to be worth more than $455bn this year. Digital advertising is delivered through complex networks of tech companies, including Google, that combine online data about people with advertising space and then sell access to those people as they browse the web.

Dr Augustine Fou, an independent ad fraud researcher and former employee of advertising agency Omnicom, says money flows to sites hosting harmful content because the system of bidding on ads means these sites get mixed in with other, more benign ones. “Because they now have a source of funding, they can not only survive but also proliferate,” he says. “And that’s why we’re seeing this huge problem.”

An advert for Amazon Pharmacy on a conspiracy theory site

An advert for Amazon Pharmacy on a conspiracy theory site

Because of the lack of transparency in this system, the companies and organisations buying the ads could be unaware that their marketing is appearing on – and potentially funding – these sources of misinformation.

“We know the ad ecosystem is incredibly opaque,” says Raegan MacDonald from Mozilla, which makes the Firefox browser. “It’s almost like we’re not supposed to look under the hood. Because if you do, you find this mess.”

MacDonald warns that the system is being “weaponised” and potentially putting public health at risk. “What I really hope is that this will be a sort of last straw for the brands,” she says.

Household names

As well as ads for consumer products, the Bureau found marketing for the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs on sites pushing falsehoods. An ad for NHS diabetes services was shown on a website that published articles from a well-known anti-vaccine activist and promoted the false claim that you cannot catch a virus.

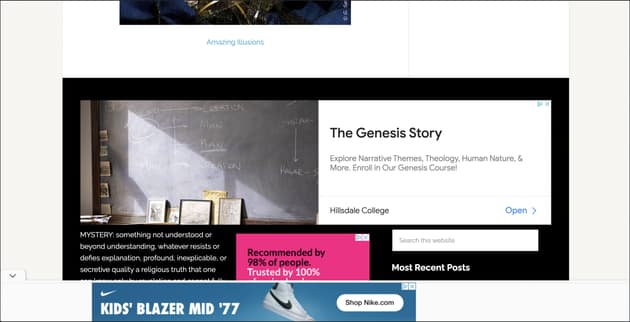

A website carrying false anti-vaccine claims …

A website carrying false anti-vaccine claims …

… as well as an advert for Ted Baker bags

… as well as an advert for Ted Baker bags

Ads for the US Department of Veterans Affairs were found on two sites, one of which wrongly described mRNA vaccines as “the genetic modification injection” and claimed they made people more likely to catch Covid. The other site repeated the false claim that the coronavirus is no more dangerous than the flu.

The Department of Veterans Affairs said it proactively blocks its ads from appearing on sites that carry misinformation, but that “due to the tempo of new information and websites that come online daily it makes it extremely difficult to guarantee that our ads won’t appear on any sites like the ones shared, but it is rare and occurs only infrequently”.

The Bureau also found charities, educational institutions and even theatre productions advertised on misinformation sites.

Some of the ads viewed by the Bureau’s journalists – such as for online clothing retailer Asos and car buying site Cars.com – appeared to be targeted based on their previous browsing behaviour. “Retargeting” uses cookies installed when users visit sites to track them around the web and show them ads related to their browsing history.

Retargeting is based primarily on tracking a person who has previously visited a site, wherever they might be on the web, and is normally designed to drive short-term sales, potentially reducing the incentives to consider the impact of where those ads end up.

Asos said it regularly reviews the sites its ads appear on and the company has “stringent requirements and processes in place to ensure that those websites align with our values”. A spokesperson added that Asos was adding the sites provided by the Bureau to its banned list.

The Bureau examined sites hosting misinformation that also delivered ads, using a combination of manual checking by researchers in the US and UK and automated systems that “crawl” sites to record what happens when someone visits them. The pages were identified with help from the Global Disinformation Index, with ad analysis provided by Rocky Moss, the co-founder and chief executive of ad quality platform Deepsee.io, and Braedon Vickers, who has built a search platform called Well-Known.

Many of the companies delivering digital advertising are little known outside the industry, but one dominant player is a household name: Google.

Analysis by Moss using Deepsee’s crawlers – which simulate a person visiting web pages – found ads delivered by Google for almost 30 big brands, each appearing on two or more misinformation websites.

The most common were for Amazon Pharmacy, the drugstore run by the online retail giant, which itself has become a major player in digital advertising. Ads for Amazon Pharmacy accounted for more than 1% of 42,000 recorded by the crawlers and were found on more than 30 of the misinformation sites.

The next most-featured advertisers were PC maker Lenovo, which appeared on 11 sites, and US bank Discover. Ads for the UK-based auctioneer Sotheby’s, Honda, US pharmacy chain Walgreens and eBay were also among those recorded on multiple misinformation-spreading sites.

Google did not directly address the presence of ads it delivered on the sites identified by the Bureau, but said it took appropriate action against sites that breached its policies on misinformation, including cutting off the ability for publishers to make money from specific pages, or their entire sites, following repeated breaches.

"Protecting consumers and the credible businesses operating on our platforms is a priority for us,” a Google spokesperson told the Bureau.

Taking responsibility

The companies that place ads on behalf of brands and other organisations often promote “brand safety” systems and services that should stop them from appearing on sites promoting unsavoury content. Other companies working in the area specialise in add-on services designed to provide an extra layer of protection. The Bureau’s investigation suggests that these systems are not functioning as well as they claim.

Of all the organisations contacted by the Bureau about their ads appearing on misinformation sites, only the Department of Veterans Affairs said that it knew which sites its ads appear on.

A spokesperson for Ted Baker said: “The location of the adverts relates to the Google Display Network which means that they are specific to each individual user. We are working with Google to look into this matter.”

Fou, the independent ad fraud researcher, says the industry has traditionally defended itself by claiming that only a fraction of advertising money can mistakenly go to sources of dangerous content on the web. But the scale of the online ad market means that even a tiny fraction of the total spending amounts to “significant money for the bad guys”.

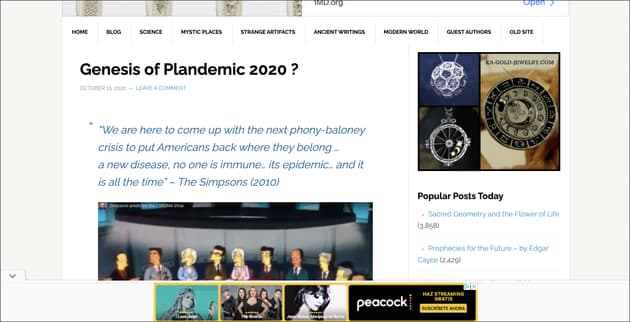

A website advancing false conspiracy theories about the 'plandemic' …

A website advancing false conspiracy theories about the 'plandemic' …

… and the same site carrying an advert for new Nike trainers

… and the same site carrying an advert for new Nike trainers

To solve the problem, he says, the companies buying ads need to conduct their own investigations rather than trusting those they use to buy ad space for them.

“All these middlemen, they’re intermediaries ... so any dollar that flows through their platforms, they make more money,” Fou says. “They don’t have an incentive to cut down […] on the brand safety issues. In fact, they have every incentive to let it through.”

Tim Elkington, the chief digital officer of IAB UK, which represents the digital advertising industry, says brands should be taking a more careful approach to where their advertising ends up.

Instead, he says, some brands appear seduced by the prospect of reaching huge pools of potential customers at low cost through the vast bidding process that puts ads in front of eyeballs. “You’re saying, ‘Look, I’m buying blind, and I don’t mind where my ad appears.’ You’re then taking a risk because your ad could literally go anywhere.”

The advertising industry runs an initiative designed to ensure that brands can see and control where their ads go. Websites host text files that declare the companies they work with to sell ad space. Analysis shows that a handful are recorded as working with multiple misinformation-spreading sites.

Among the most commonly cited partners in the declarations of the misinformation sites examined by the Bureau was Consumable.com. It promotes its services with the line: “In an industry of promoted clickbait and fake news, Consumable offers only truly premium entertainment content.” It did not respond to the Bureau’s request for comment.

Another was Next Millennium Media, which was recently described as a “dark pool sales house” by brand safety investigator Check My Ads. “Dark pools” provide misleading transparency data, including through the text files hosted by sites, helping to obscure the destination of the ads and the money paid for them. Next Millennium Media did not respond to the Bureau’s request for comment.

Mozilla’s MacDonald says brands need to shoulder their share of the responsibility for ensuring the advertising systems they use are safer and more transparent, but that digital advertising is a “convenient system” where you can “pass the buck”.

“Many of these big brands have been talking for years about the need for more transparency. They talk a lot about trust being a very important part of the brand,” she says. “It’s not in their best interest to have their brands appear on harmful websites. They need to step up and do something.”

Header image: A pair of Nike trainers on display in a shop. Credit: Lee/Bloomberg via Getty

Reporter: Jasper Jackson

Additional reporting: Ben Stockton

Impact producer: Paul Eccles

Desk editor: Chrissie Giles

Global editor: James Ball

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Production editors: Emily Goddard and Alex Hess

Fact checker: Lowri Daniels

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Infographic: Kate Baldwin for the Bureau

This article is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: