Evicted in less than 10 minutes: courts fail tenants broken by pandemic

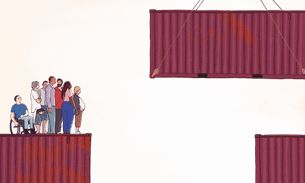

People in dire financial straits are losing their homes in a matter of minutes because of a legal system that has failed to account for the catastrophic impact of the pandemic, with judges powerless to prevent evictions being ordered, the Bureau can reveal.

At the start of the pandemic, the government said no one should lose their home as a result of coronavirus. But despite campaigners warning that the pandemic would lead to a “cliff edge” of evictions, nothing has been done to address the fact that a judge is required to grant a possession order – paving the way for eviction – against any tenant who falls two months behind on their rent.

Now, an unprecedented analysis of 555 recent possession court hearings involving rented properties in England and Wales reveals that 85% of cases leave judges with no scope to take a tenant’s circumstances into account. The impact of Covid-19 was explicitly mentioned in a third of all hearings where a possession order was granted, yet the existing rules left judges with no choice but to order an eviction.

People we saw handed an eviction order on these grounds included a pregnant woman whose work had dried up because of Covid-19, a man who had suffered a mental breakdown and whose wife was hospitalised with Covid-19, and a woman who had become depressed after quitting her job to start another that never materialised because of Covid-19. Some possession orders were granted in under a minute.

One in five cases involved the controversial Section 21 “no fault eviction” notice, which states that landlords do not need to give a specific reason for wanting a tenant out. Lord Bird, founder of the Big Issue, told the Bureau: “It’s clear that the government must act now to suspend no fault evictions. We need to keep people in their homes at all costs – or we risk facing a mass homelessness crisis like never before.”

Until now, little had been known about the pandemic’s impact on those struggling to keep a roof over their head. The Bureau sent a team of reporters to 30 courts across England and Wales, gathering information that provides an unparalleled insight into how the pandemic has affected housing. We found:

Life-changing decisions that often leave people homeless are made in an average of nine minutes and 40 seconds. A third of cases where a possession order was granted took five minutes or less.

The vast majority (85%) of cases logged were on legal grounds that meant a possession order was mandatory, affording the judge no discretion to factor in a person’s situation.

The impact of Covid-19 was mentioned explicitly in one third of all cases where a possession order was granted.

One in five cases involved Section 21 “no fault” orders. The Conservative party promised in 2019 to scrap Section 21 and the government told the Bureau it would set out proposals to repeal the legislation “in due course”.

In just under 60% of hearings neither the tenant nor their lawyer was in attendance – so no one was there to argue against the eviction.

In nearly one in five (18%) hearings where the tenant was represented in court, they mentioned having children.

Landlords complained of being owed thousands of pounds and were frustrated by court delays caused by the pandemic.

MP Clive Betts, chair of the housing, communities and local government committee, said: “It is saddening to read the results of this research, which show that huge numbers of renting households, including families, have been pushed out of their homes since the lifting of the evictions ban.

“As the pandemic continues and we head into winter, there remains a need for urgent government action on these issues to help avoid evictions and the devastating impacts of homelessness.”

In carrying out this project, our court reporters met various obstacles. Despite possession courts being open to the public, we were repeatedly stopped from attending hearings by judges who wrongly believed all cases should be private. Some had never seen a journalist in their court before. One judge told a reporter they would not be allowed in without written permission from a senior judicial figure. But despite this, our reporters sat in more than 100 hours of possession hearings.

An inflexible system

Mohammed* was among the people whose cases were decided in a matter of minutes. He leaned back in his chair and sighed when the judge sealed his fate: he would be evicted, along with his wife and three children.

He had wanted to speak in court: to explain that he had been hospitalised for a mental breakdown and was unable to continue doing his job as a taxi driver. To explain why, as the only bread-winner in his family, he could no longer pay the rent.

He wanted to say that his wife had just come out of hospital, having been in intensive care with Covid-19. He wanted to offer to try and pay some of the £5,000 or so they owed in rent. But every time he tried to speak, the judge silenced him.

“The problem is, this is ground 8 – mandatory ground – and the claimant has fulfilled all the criteria,” the judge explained. “I’ve no option but to grant possession.” Mohammed and his family were given 42 days before the bailiffs would be called in.

“They never listened,” Mohammed told the Bureau. “They should have said, ‘Do you want to say anything?’ Even if they said, ‘Pay a couple of grand now and pay the rest later’, we would have sorted something out, you know, borrowed it, but they never said anything.”

As he made plans for his children to stay with relatives and friends while he looked for a new family home, his 13-year-old daughter asked whether they would need to sleep rough.

Mohammed’s story is not unusual. When the first lockdown in early 2020 drew bleak economic forecasts, politicians and campaigners warned that an onslaught of evictions was imminent unless urgent changes were made to rental laws. The Housing Act 1988 lays out “mandatory grounds” for eviction, meaning as long as procedural rules are followed, such as giving the right amount of notice, a tenant has no legal argument against eviction.

The Housing, Communities and Local Government committee of MPs went so far as to draft example legislation, suggesting a temporary pause of these rules. The committee argued that judges should be allowed to use their discretion to weigh up the impact of the pandemic in each individual case. They also warned of the consequences of Section 21 “no fault” eviction notices.

All those warnings went unheeded. Instead, possession hearings, which deal with eviction issues, were simply paused in March 2020 before starting back up again in September 2020. A ban on bailiff evictions was lifted in May 2021 in England and the following month in Wales.

The amount of notice landlords had to give tenants to get out of the property was extended, but will return to pre-pandemic timescales on 1 October.

Just under two thirds (63%) of the hearings we attended involved the mandatory ground 8, where a tenant can be evicted if they owe two months’ or more in rent. The average tenant was £6,500 in arrears. But in many cases tenants only just reached the bar for eviction. In around a quarter of cases the money owed was £3,000 or less, equivalent to less than three months of the average UK rent. In one case a tenant owed just £292. Judicial advice to courts had been to prioritise the most extreme cases, such as 12 months of arrears.

Covid-19 was often mentioned explicitly with regards to the tenant’s situation but judges repeatedly explained that personal misfortunes made no difference. One said his “hands were tied”, another said there was nothing he could do, a third said there was “no suitable alternative” but to grant the order.

One million more people in the UK are claiming unemployment benefits now than before the pandemic, according to the latest data, and 1.9 million jobs have been put on furlough. Those hardest hit include ethnic minority groups, women, young people, low-paid workers and people with disabilities.

Anyone can get legal support, financed through Legal Aid, for a possession hearing where they are facing eviction. The Bureau found that 17% of those that received this support were Black British – a group that makes up 3% of the general population – suggesting that there is a disproportionately high number of Black people facing evictions in the courts.

As the government’s furlough scheme winds up at the end of this month, some campaigners have expressed concerns that unemployment will rise, and with it, housing debts. While governments in Scotland and Wales announced grant schemes to help tenants keep their homes and ensure landlords did not lose income, no such measure was introduced in England.

Polly Neate, chief executive of Shelter, said: “The financial shockwaves created by the pandemic have left many renters fighting to stay afloat, with thousands facing mounting debts and ‘Covid arrears’ they have little hope of paying off. With only days until the Covid protections of furlough and the Universal Credit uplift are removed, more renters will be in danger of losing their homes in the months ahead.”

Nick Ballard from tenant rights group ACORN said the Bureau's findings were “absolutely harrowing”. He added: “The government completely failed to tackle the underlying factors of unaffordable housing and poverty, while merely kicking the can down the road throughout the pandemic. It is unconscionable that people are losing their homes due to arrears accrued solely during a global pandemic.”

No fault evictions

Rudy Bozart worked as a production assistant for a company that went bust during the pandemic. Trying to find other work, he became an agency care worker and delivered food with Deliveroo and UberEats, but his debts kept rising. “I never had any issues with credit or with debt, but within one year the pandemic financially destroyed me,” he said. He fell behind on rent.

The day after the bailiff ban was lifted, his landlord presented him with a “no fault” eviction notice. With huge debts and no money for a deposit, he has found it impossible to find somewhere else to rent.

One in five of the hearings we witnessed involved controversial Section 21 “no fault” evictions, where the landlord does not need to give a specific reason for wanting possession of their property. More than 8,700 people in England approached their council as homeless because of a “no fault” eviction in the year to March 2021.

Rudy Bozart was given a Section 21 notice and has struggled to find somewhere else to live.

Eleanor Church

Rudy Bozart was given a Section 21 notice and has struggled to find somewhere else to live.

Eleanor Church

The Conservative party pledged in its 2019 manifesto to abolish “no fault” evictions in order to create a “fairer rental market”. In September last year, Christopher Pincher, the minister for housing, said the issue would be addressed “at the appropriate time”. No changes have been made in the 12 months since. The government told the Bureau it will appear in the Renters’ Reform Bill, but no exact dates or details have been given.

Lord Bird said: “We cannot wait for a Renters' Reform Act to be passed when there is evidence that people are losing the place they call home through no fault of their own. The government must be held to account on their promise that nobody would be made homeless because of Covid-19 related poverty.”

And our court findings are just the tip of the iceberg: many Section 21 claims never make it as far as a court hearing. Since the start of the pandemic 15,126 accelerated “no fault” eviction claims have been processed on paper rather than through in-person hearings.

Alicia Kennedy, director of the Generation Rent campaign, told the Bureau: “Because tenants cannot challenge a valid Section 21 notice, many will move out before the case gets to court, so the true number of these cases will be much greater than the figures from court suggest. The fact that any cases where the tenant was not shown to be at fault were heard in court is a failure of policy.”

With nowhere else to go, Rudy’s only option is to wait for his day in court, though he is not optimistic about the outcome. He says the stress of waiting is causing his hair to fall out. “It is absurd to think there is a Section 21 notice and the judge can’t do anything against it,” he said.

“It would be so nice if the government would say: ‘Look, we know the eviction ban has ended but now we are going to go case by case and give powers to the judges […] if the base ground is rent arrears.’ I am not withholding money from my landlord. I can't give something I don't have.”

Other people the Bureau spoke to who had been given a Section 21 notice included a 56-year-old woman whose husband had terminal cancer. The couple had lived in the same rental property for 10 years and worried about leaving the community.

Another was a 78-year-old woman who had been repeatedly told by estate agents that they wouldn’t rent to someone receiving a pension. She described the threat of being unable to find a home before the bailiffs arrived as “terrifying” and said she had visited around 50 properties, before finally finding one that would consider renting to her. She and others mentioned landlords and agencies that were asking for up to six months’ rent in advance.

Landlords in trouble

It is not just tenants who are suffering. Amar bought a house as an investment and rented it out to a couple. When the pandemic hit, his tenants told him they would no longer be able to pay rent – and he realised they had given false information about their jobs and guarantor.

He said he would have been happy to write off the unpaid rent when he first served notice, but the case took so long to get to court that now he was owed such a substantial sum he would have to claim it. “By the time they leave, they will owe us the best part of £8,000,” he said. “Whilst I understand that tenants ought to have some protection, the court system and lengthy procedure allowed this to take place.”

Many private landlords have seen their income dry up thanks to the moratorium on proceedings and the courts’ reduced capacity. One private landlord whose hearing the Bureau witnessed was owed as much as £94,000.

In some cases landlords told judges they were seeking possession of their property so they could move into it themselves. In one instance, a landlady was fleeing domestic abuse. In another, the bereaved family of a landlord was trying to get the property back to sell as they were in mounting debt.

According to the government’s own figures, “45% of private landlords own just one property and are highly vulnerable to rent arrears”.

A spokesperson from the National Residential Landlords’ Association told the Bureau: “Landlords want to keep tenants in their properties wherever possible, but they cannot be expected simply to shoulder the cost of rent arrears indefinitely.

“The government needs to follow the examples set in Scotland and Wales and provide the modest financial support needed to help tenants pay off arrears built since lockdown measures started last March. Without it, affected tenants face the prospect of losing their homes and the damage to their credit scores will preclude them from accessing new housing in the future.”

While landlords and home-owners have received financial support in the form of the offer of mortgage holidays and reduced stamp duty fees, rental tenants had no such support.

Social landlords

The Bureau also analysed court listings for 10 of the busiest possession courts in England and Wales that saw more than 2,000 cases (review and substantive hearings). While most involved private landlords, social landlords such as housing associations accounted for 24% of claimants and local authorities another 13%.

Councils have found themselves under pressure, acting as landlords to some while being the first port of call for others who find themselves homeless after being evicted. While several councils called for the eviction ban to be extended, some have been taking people to the courts. In the first three months after the ban of bailiff evictions was lifted, Islington council initiated at least 43 hearings, Lambeth council brought cases against at least 31 tenants and Nottingham city council brought at least 44 people to possession courts.

Nottingham council said less than half these cases were for rent arrears and that it always tries to offer support before resorting to possession proceedings. It added that if tenants do not engage with them, “we will seek possession so that these homes can be given to other families who are on our waiting list”. Islington council told us that beginning an eviction case is “always an absolute last resort” and that in none of these cases has a tenant been evicted so far.

The National Housing Federation, which represents not-for-profit housing associations, committed in May to pursue evictions “only as a very last resort”. But a quarter of cases in the court lists we analysed were brought by housing associations. Sanctuary Housing Association, for example, brought 35 cases across five courts.

In court, some social landlords complained that tenants were failing to engage with services offered. Many used the court proceedings as a means of trying to force people to engage; some asked the judge to suspend possession orders, which allows the tenant to stay in the property if they adhere to strict conditions.

The worst still to come?

Despite the speed at which cases are being heard, many courts are not yet functioning at full capacity. The number of possession orders granted by courts – though they have more than doubled since last winter – are at only a third of the typical number pre-pandemic.

Citizens Advice estimate that half a million people could be in rent arrears, and one in four of them have been threatened with eviction. One housing solicitor said they feared a “tsunami” of evictions was “just around the corner”.

Alicia Kennedy, director of Generation Rent, said: “The pandemic has reminded us painfully of the need for a safe, secure home. The government cannot take us back to the old rental market, where tenants have no idea where home will be in a year’s time and a sudden unavoidable loss of income can put your home on the line. As ministers finalise the long-awaited tenancy reforms they must apply the lessons and make sure that anyone facing eviction has a chance to make their case to stay put.”

A government spokesperson told the Bureau: “Our £352bn support package has helped renters throughout the pandemic and prevented a build-up of rent arrears. We also took unprecedented action to help keep people in their homes by extending notice periods and pausing evictions at the height of the pandemic.

“As the economy reopens it is right that these measures are now being lifted and we are delivering a fairer and more effective private rental sector that works for both landlords and tenants.”

*Some names have been changed

Reporting team: Maeve McClenaghan, Emma Bartholemew, Nathalie Raffray, Sabah Hussain, Tom Fair, Sam Baker, Reece Stafferton, Ruth Bushi, Shahed Ezaydi, Tommy Greene, Alexandria Slater, John Brace, Finn Oldfield, Patrick Ferrity, Michelle Ferguson, David Landau, Fatima Hudoon, Ben Fishwick, Rebecca Speare-Cole, Siriol Griffiths, Nick Thomas and Jacob Moreton

Community organiser: Eve Livingston and Emiliano Mellino

Bureau Local editor: Emily Wilson

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Data analysis: Charles Boutaud and Maeve McClenaghan

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Photography: Eleanor Church

Illustrations: Alice Mollon

This project is funded by the Legal Education Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: