BlackRock tells oil regulator: ignore our CEO’s climate pledges

BlackRock, the world’s biggest asset manager, has backpedalled on its chief executive’s climate-conscious public statements in a private meeting with a US regulator, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism can reveal.

Larry Fink has urged businesses to prepare for a carbon-free future and said BlackRock, which manages more than $10tn in assets, would put sustainability at the heart of its investment decisions.

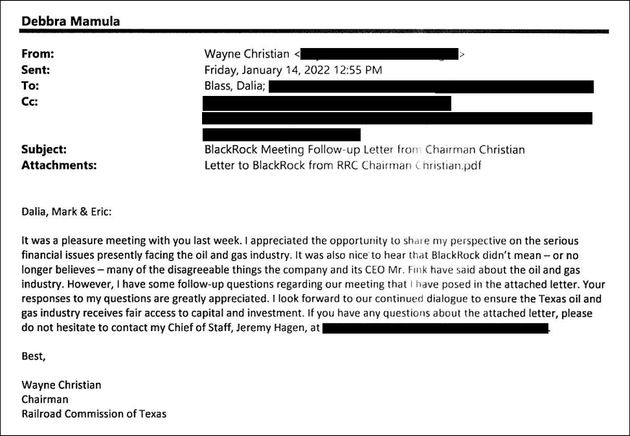

However, in an email sent after meeting BlackRock executives last month, the chairman of Texas’s oil and gas regulator wrote: “It was nice to hear that BlackRock didn’t mean – or no longer believes – many of the disagreeable things the company and its CEO Mr Fink have said about the oil and gas industry.”

The email was uncovered via freedom of information requests sent by the Bureau and the thinktank InfluenceMap.

BlackRock joins several major banks – including Barclays, Citigroup and Wells Fargo – that have quietly downplayed their environmental commitments so they can keep doing business with deep-pocketed US states.

In November, 15 US states – responsible for more than $600bn in funds – wrote an open letter to the banking industry in which they threatened to withdraw their business from financial institutions that boycott fossil fuel companies.

Texas has already passed a law to that effect and other states are preparing similar legislation, setting the stage for a showdown with banks and asset managers that have pledged to wind down their financing of fossil fuels.

Due to pressure from some investors, most banks have policies in place to limit the business they do with coal-fired power, one of the dirtiest forms of energy generation.

Although these policies are often carefully crafted to include significant loopholes, the laws being drafted by US states leave little room for interpretation and could force banks to make a choice between their climate commitments and big business opportunities.

US Bank, the country’s fifth largest bank by assets, appears to have bowed to pressure from Texas, changing a policy that prohibited it from financing coal-fired power plants so as not to specify any one form of energy generation.

Senator Sheldon Whitehouse told the Bureau: “It does not sound like these financial institutions are taking their climate commitments seriously, and they can’t have it both ways. If they have not been honest with investors about their climate policies, then this is certainly a matter for [US financial regulator] the SEC to look into.”

BlackRock meeting

In January BlackRock sent a team of senior staff – including Dalia Blass, its head of external affairs – to meet Wayne Christian, a former Republican legislator who has chaired the state’s oil and gas regulator since 2016.

In his follow-up email to Blass, Christian noted the BlackRock team had said their environmental, social and governance (ESG) initiatives had been misrepresented by the media and that the company was “supportive of the oil and gas industry and merely offers ESG energy-related investments because of client demand”. He questioned BlackRock on the contradictions between these reassurances and its public stance on climate issues.

Blass had already written to Texas officials to highlight BlackRock's support for the fossil fuel industry. “We are perhaps the world’s largest investor in fossil fuel companies,” she wrote. “We want to see these companies succeed and prosper.”

A BlackRock spokesperson told the Bureau: “We focus on climate not because we’re environmentalists, but because we are capitalists” and they have a financial responsibility to their clients. They added: “BlackRock has been clear and consistent since January 2020 that climate risk is an investment risk that will impact returns […] Our investment conviction is that sustainability- and climate-integrated portfolios can provide better risk-adjusted returns to our clients.

“BlackRock has long stated that energy firms play an important role in the global economy and in a successful transition […] In both public and private engagements, including in Texas, BlackRock executives are consistent on these points.”

The spokesperson said BlackRock does not pursue divestment from sectors as a policy.

Larry Fink wrote of a "tectonic shift towards sustainable investing" in his annual letter to CEOs.

Justin Chin/Bloomberg via Getty

Larry Fink wrote of a "tectonic shift towards sustainable investing" in his annual letter to CEOs.

Justin Chin/Bloomberg via Getty

Energy boycott

Banks too are under pressure after November’s open letter from 15 state treasurers saying they would only do business with financial institutions that “are not engaged in harmful fossil fuel industry boycotts”.

The letter criticised the Biden administration for calling on US banks to limit or refuse financing for fossil fuel-related companies. “These misguided political schemes have impeded economic growth, driven up consumer costs, and regressed our country to foreign energy dependence,” the state treasurers wrote.

One of the largest banks in the US sent a warm response to the state treasurer of West Virginia, who coordinated the letter.

US Bank replied saying it hoped to maintain its relationship with West Virginia – a major coal producer – for many years to come. In a note, Tim Rieder, senior vice president, added: “Personally, I totally agree with the [treasurers’] letter.”

US Bank’s subsequent policy change may be a harbinger of what is to come as states begin to take concrete steps to blacklist institutions that discriminate against the fossil fuel industry. Texas is the first to have done so, having implemented a law requiring financial institutions to certify that they do not boycott energy companies in order to remain eligible to do business with the state.

It defines boycott as terminating business activities, limiting commercial relations or taking any action that would inflict economic harm to a company because it is involved in the production, use, transportation or sale of fossil fuel-based energy.

US Bank is one of 39 financial institutions to have submitted one of these letters, which appears to contradict the environmental policy it had in place at the time. Barclays, Citigroup, UBS, Wells Fargo and RBC Capital Markets have also submitted letters; all five have policies that put limitations on their financing of coal-fired power.

Make change possible

Investigative journalism is vital for democracy. Help us to expose injustice and spark change

Click here to support usThis apparent contradiction has not escaped the notice of federal regulators. Reuters has reported that the SEC is investigating a number of banks that have acted as underwriters for Texas. It is said to be scrutinising potential conflicts between what the banks told Texas regulators and what they told their own investors about their fossil fuel policies.

Danielle Fugere, president of As You Sow, an environmental campaign group focused on shareholder advocacy, says this raises serious questions for investors. “How does the bank square this type of broad commitment to the state with their commitment to reduce their own financed emissions?”

Citigroup told the Bureau: “Our policies are focused on responsibly managing the energy transition, not boycotting the energy sector. This position has been communicated consistently to all of our stakeholders.”

Barclays said: “We are aligning our entire financing portfolio to the goals and timelines of the Paris Agreement, on the way to becoming a net zero bank by 2050.”

UBS said it supports the goals of the Paris agreement and added: “We view engagement with companies in all industries as fundamental to any sustainable investing approach.”

US Bank said it had not changed its policy under pressure from US states and that its investment policy had not prohibited financing coal-fired power since October 2020. However, its 2021 environmental responsibility policy, displayed on the bank’s website until last month, did prohibit US Bank from financing coal-fired power.

Wells Fargo and RBC Capital Markets declined to comment.

Adam McGibbon at Market Forces, an activist group focusing on the link between the environment and finance, said: “Banks that are serious about the climate crisis don't shift principles depending on who they're talking to. How can anyone trust these banks on climate change when they're giving different stakeholders contradictory messages?”

For its part, BlackRock is still attempting the high-wire act of placating investors focused on ESG issues while reassuring its clients in the fossil fuel industry that it has no intention of cutting off their funds.

That has failed to impress West Virginia, which has said it will not use a BlackRock investment fund because of reports that it has “urged companies to embrace ‘net zero’ investment strategies that would harm the coal, oil and natural gas industries”.

Despite BlackRock’s charm offensive in Texas, a high-placed official is still urging the state to place the company on its blacklist.

The state’s lieutenant governor wrote in a statement: “At the meeting with my staff, BlackRock said it was committed to Texas and Texas’s vast energy footprint, but I have grave concerns that BlackRock’s public statements and actions do not reflect its sentiments presented to my office.”

Header image: Climate activists protest outside BlackRock's New York headquarters in October. Credit: Erik McGregor / Getty

Reporter: Josephine Moulds

Environment editor: Jeevan Vasagar

Impact producer: Grace Murray

Global editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

This reporting is funded by The Sunrise Project. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: