‘Please Acknowledge the Dick’: Inside a catfishing factory

Content warning: This story involves discussion of sexually explicit messages, racism and suicide.

Remote workers often get a message when they log on. But the ones at “fantasy-based text network” Texting Factory are a little different.

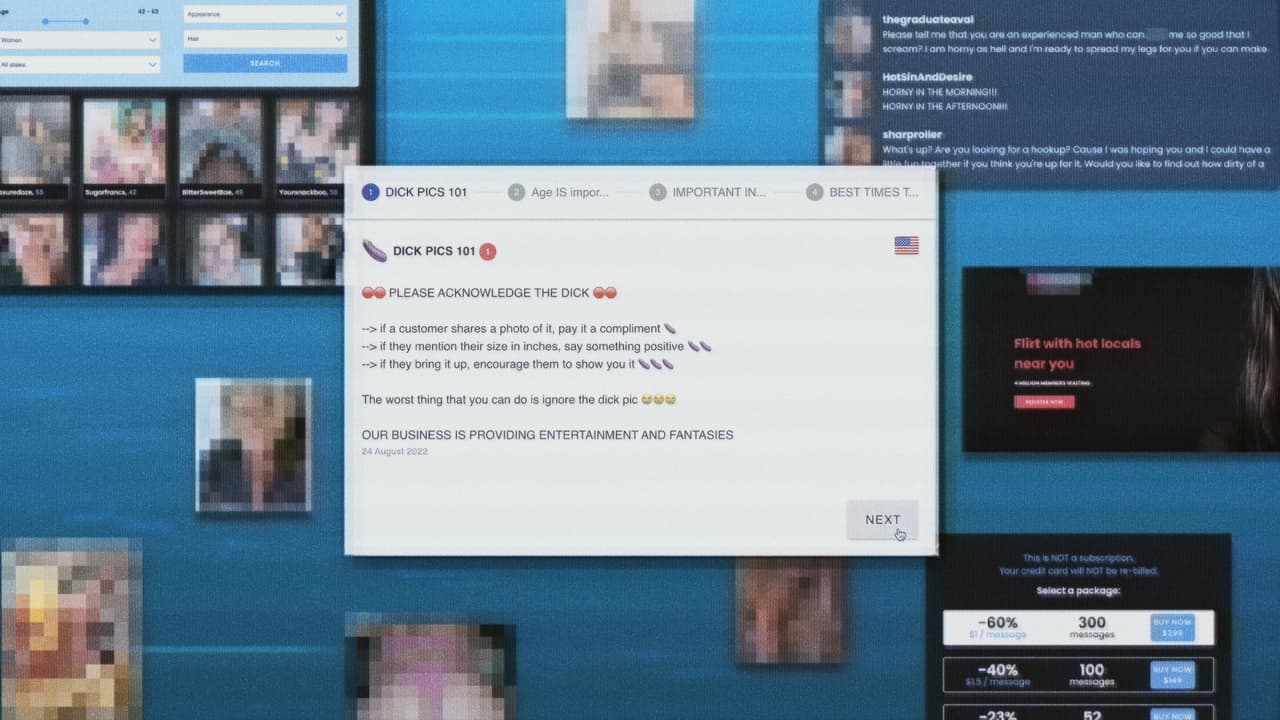

DICK PICS 101

PLEASE ACKNOWLEDGE THE DICK

-> if a customer shares a photo of it, pay it a compliment

-> if they mention their size in inches, say something positive

> if they bring it up, encourage them to show you it

The worst thing that you can do is ignore the dick pic

OUR BUSINESS IS PROVIDING ENTERTAINMENT AND FANTASIES

Once operators have read and digested this popup – and then skipped past reminders about the best times to be online – they are dropped into their first chat of the day.

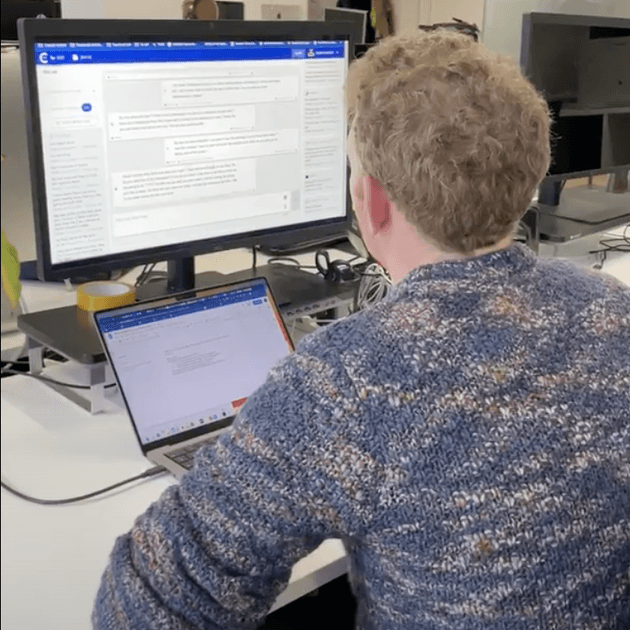

The first job is to write a response as “alonneagain”, a 26-year-old whose profile indicates her "real" name is Julie, with pictures suggesting she likes to pose outdoors in a bikini. Her bio reads: “I'm looking for a regular fling. I need a hot man who knows how to put the moves on me and my body. I am horny and don't think I can wait any longer, please come and release me, ASAP.”

The problem is, Julie isn’t real. Today, "alonneagain," is actually a 37-year-old man in London, working undercover to investigate the platform in a joint investigation for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and VICE World News.

The job is being a “chat operator”, one of the remote workers paid a pittance to play the roles of wholly fictional eager and unsatisfied women messaging men who sign up for sex-chat services with names like “onlyflirtshere” and “twomance”.

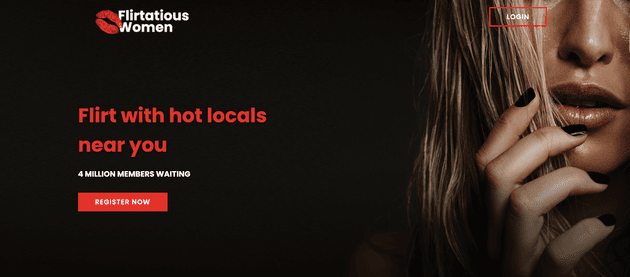

The chat services are linked to sites like this, where people can pay to message women

The chat services are linked to sites like this, where people can pay to message women

“Julie” is a character, staffed by different people working across the globe who each play many different women. Operators, wherever they are, have a bank of photos of the women they play, and made up information, such as her likes (beer and burgers), her dislikes (her marriage), and location (somewhere near, but not too near the man she’s chatting to). On one side of the screen is a constantly updated fact-file about the man they are speaking to – where he works, what his marital status is, any information about how he spends his spare time, to avoid operators asking questions their character is expected to know and raising the customer's suspicions that they are not who they say they are.

Operators at this catfishing factory make cents per message, and those who spoke to the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and VICE World News said they often had to deal with aggressive and sometimes suicidal customers, as well as dick pics and sexually explicit messages, to which they are encouraged to give equally explicit responses. Some described arbitrary pay deductions from their already small payslips and being kicked off the platform with little explanation.

On average the base rates provided by operators worked out at $0.06 per message – meaning that to earn just $60 they would have to send 1,000 messages. Even if each message, which must meet demanding quality requirements, took just 30 seconds, that would require an eight-hour day without breaks.

The purpose of all this, hammered home to the operators through a brief but demanding training done over an online portal and Skype, is to get the men using the services to keep sending more messages, using up a credit that costs more than $1 per message. The disparity between what men pay and workers earn suggests that someone, somewhere, is making a lot of money.

The conversation between “alonneagain” and “hut4you69”, an 83-year-old man, has hit a tricky point, and I stare at the screen trying to work out what to do. “hut4you69” is getting agitated, because he wants to take the conversation off the sex chat platform – he wants “Julie” to call him, something operators are explicitly forbidden from doing.

A previous message “Julie” sent, crafted by the last person working on the account, didn’t do the trick. That operator had tried: “I’m sorry, don’t you think it would be too fast to call each other on the phone? We just started talking here and I still don’t know you yet that much.”

His response: “I do not want to message any more. If you want to tell [sic] you have my number or not this is my email.” What do you tell an old man who wants more from his fictitious young admirer, without breaking character?

The best option seems to be emotional manipulation. I type: “So I need to be honest, I just feel a lot safer chatting here until we get to know each other a bit better. Work out if we will work together in person. I've had bad experiences with people when I've given out my number too early. You understand that, don't you?”

After checking the grammar and spelling are perfect – quality standards again – I click send. A wheel whirrs, a loading bar pops up, and then that conversation vanishes and another conversation appears. Suddenly I am “PaintStrokes”, 58 years old, talking to “bronc6tx”, 62, about the time he realised his partner was sleeping with someone else.

As the timer telling me how long I have to come up with a reply ticks down from five minutes, I try to think of an appropriate response that will pique his curiosity or give him hope we will one day meet, all to get him to message again.

Undercover as a chat operator

Undercover as a chat operator

Texting Factory, the catfishing company we signed up for as part of our investigation, is just one of the many sex chat messaging businesses operating in this ecosystem.

The Bureau and VICE World News spoke to a mix of male and female operators – who always posed as women – scattered across the Philippines, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, the Caribbean, Latvia and the UK. All had worked for one or more of nine companies we identified as employing people to sex chat. All wanted to remain anonymous because they were still working for the platforms, or did not want their work as a chat operator to be made public.

The testimony of the operators, and documents we were given during training or passed to us, show a surprisingly sophisticated and regimented industry plugged into sex chat sites. While workers are drawn from across the globe, the service is aimed mainly at the US market, with some customers in Europe.

Despite subtle disclaimers on the sites saying the messaging service is for “designed for pleasure and entertainment,” most of the men appear to believe they are chatting to real women who find them sexually attractive, care about them, and may even one day meet them in real life. The bulk of the conversations are far more sexually explicit and graphic than what was sent to “hut4you69” or “bronc6tx”.

For example, one of the messages waiting for a response was from a 74-year-old man which said: “I have never rimmed anyone do you like cock in your ass? I really have to be talked into pegging I don't think I would like it either.”

Operators are given detailed instructions about how to write their messages, and receive a score based on how effective they are at getting men to respond. Each must be unique with perfect spelling and grammar. For Texting Factory, messages must always be at least 75 characters, and operators should aim for more than 150. They should be able to reference a previous line in the conversation or pull something from the ever-updated file compiled about each customer. When needed, to keep a man interested, they should send one of the pictures attached to the profile, which are described in training as “bait” and are often sexually explicit. Some of those that came up during the investigation included a blonde woman in a pink thong bending over and an older woman masturbating.

Perhaps most importantly, every message should always end on a question to elicit that valuable, paid-for response.

As the Texting Factory training materials put it: “It is your job as an operator to keep the customer’s interest, curiosity and hope alive, ensuring he is buying more credits and continuing the conversation on our platform.”

“I had to work so much, like 10 hours a day, just to earn a decent amount. That’s why I stopped. It’s good part-time, but you can't actually depend on it,” said Paula, an operator from the Philippines. “Eight to 10 hours, you're gonna get a decent amount, 5,000 (£74 or $90) to 7,000 (£100 or $130) pesos [a week].”

The rate of pay varies based on how many messages are sent and what time of day operators work, with peak times for those based far from the US often landing in the middle of the night. Operators regularly told us they were pressured to put in more hours on the job and were sometimes kicked off the platform if they refused.

“They had a minimum number of hours somebody had to work, like, a normal week. But during festive periods, they would ask us if we're available to put in more hours,” said Tendai, an operator based in Zimbabwe who was terminated after refusing to work more hours.

Errors or copying and pasting could mean deductions from already tiny paychecks, suspension or deactivation. Operators told us that they were often confused about why they were being punished. Some said they were kicked off the platform for unclear reasons, although they could often simply sign up again.

“The ugly thing about it is that there’s no mentorship or what. Anytime they could cut you off, they’re gonna cut you off,” said Althea, who worked from the Philippines for Texting Factory and another service. “No explanation, you cannot reply ... you’re cut off, that’s the end of the deal. “

When the men inevitably ask to meet, or to message on another platform, excuses have to leave the customer with hope, even if they are flimsy. “I’m sorry I have a dentist appointment tonight” or “I dropped my phone and it’s in the repair shop.”

But these don’t always work. When customers get angry, operators are encouraged to keep responding, almost no matter what.

“I had a few of them get really nasty. Not too many. But some of them got like, really aggressive,” said a UK based operator, Laura. “I actually got told off for that because someone got really aggressive with me and I said something back that I probably shouldn't have. I can't remember what it was at the time, not anything that bad.”

According to an email sent to Texting Factory staff : “Being rude is never tolerated within our company… Remember, no matter what these people say to you you're getting paid. So put on your roleplaying hat and answer those messages with a smile!”

A training document for another similar company, Cloudworkers, says that if customers are racist, the operator should politely encourage them to stop making those remarks, and operators should only move the conversation to a “panic room” to be dealt with by team leaders if they continue. It is unclear whether members are kicked off the platform for this kind of behaviour.

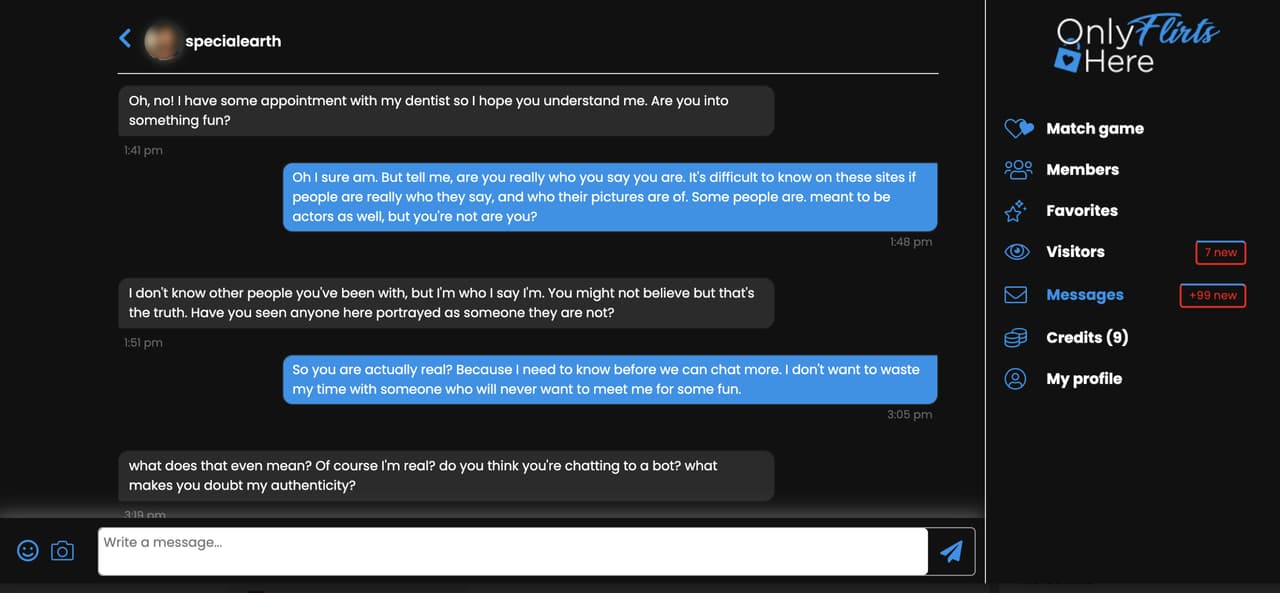

The Texting Factory training says that it is “assumed” that customers know the characters they chat with are fictitious – after all, customers have to click through a disclaimer. Yet all of the training for operators is aimed at making sure the customers believe they are chatting to one, real person.

“NEVER EVER reveal that you work as an operator and get paid to chat”, reads one slide from Texting Factory’s training materials, which goes on to say that doing so is a violation of recruits’ signed confidentiality agreements. Operators are told that it is only if they are “specifically and directly” asked if they are real that they should reveal they are just “here to chat and physical contact is not possible”.

“You really cannot say that you're fake. You cannot say anything that will lead to the idea that it’s a scam,” said Althea. “Even if the guy is saying that ‘I've been wasting money on this platform for years, and I can see that you're really fake. This is just the profile made by scammers and blah, blah, blah’, you need to make that person believe that you're a real person, and you’re gonna send pictures again.”

Paula added: “I think our company, [in] the terms and conditions, it says that if the profile has a butterfly or has some kind of icon, it means that the girl is not real. So if they read the terms and agreement thoroughly, then they would know that our account is not real. But they don’t usually do that.” None of the profiles viewed during this investigation appeared to be real.

When the Bureau posed as a customer on one of these sex-chat sites and asked whether we were talking to someone real, a message came back promising that the character was, in fact, who they said they were.

In the course of its reporting the Bureau and VICE World News found evidence that one man had been talking to the same character – but operated by multiple people – for three years. One of the operators we spoke showed us a screenshot of a different conversation on another platform that had also started three years earlier. Another customer said in a conversation on the Texting Factory platform that he had spent more than $1,000 on messages.

“The majority of the people that we’re talking to are lonely. There's a reason why they are spending money on that platform, just in order for someone to listen to them,” Althea said. “When you get to chat with younger guys, they're just like dogs, fucking dogs. Super horny. But when you chat with 45, 60, 70, they're more after communication.

“There are chatters from the UK, they’re in a (retirement) home. The only thing that they have with them is their phone and the platform. Some of their family do not visit them anymore. So if they need someone to talk to, chat, especially at night, they're gonna use that platform to have someone to talk to.”

Angelo, another operator from the Philippines who worked for four different platforms including Texting Factory but not Cloudworkers, said that if a customer indicated they were considering suicide they would try to pacify them. “‘I care for you’. You send them those kinds of messages. ‘I care for you, don't do it.’ You will try to control everything, you will try to pacify the client,” he said.

Texting Factory training tells operators not to engage in conversations about suicide, while Cloudworkers lists this as a reason to move a conversation to a “panic room”. However, there was no evidence of any support for operators who encountered suicidal customers.

While most operators are told never to give a concrete invitation to meet in person or have sex, other workers are employed specifically for this purpose. Called “pokers” on Texting Factory, they will send opening messages that are often incredibly sexually explicit, asking to meet or chat on WhatsApp. We believe they are more experienced, and possibly better paid.

Despite this, the conversation never actually moves off the platform, and no one meets the customer. It’s just another tactic to keep the messages coming. Once a man responds, operators are tasked with keeping them on the hook. And if the conversation wanes, “trigger” messages are sent in an attempt to re-engage the customer, and get them to send more paid-for messages.

“Different things that you would do on the team, you get a different pay for that. The teams that I'm aware of are the chat team who messages the clients, the poke team who does like, interim messaging, and then you have the profile creators,” said Joseph, who worked for Texting Factory.

The trainer messaged over Skype: “You will see in some cases, there will be some very aggressive pokes sent out where the player is initiating to meet or asking the client to come over or even for a phone number… redirect the client, throw him off, change the topic, avoid meeting up and give him something else to think about. Be creative and don't be nervous.”

On Cloudworkers, training manuals give examples of opening messages that may have been sent, including suggestions to move to WhatsApp, which must then be postponed, and “offering up her virginity because all her friends have lost it.”

Those employed to craft the characters, who are paid per profile, have to write short bios to match photos, some of which seem to also be on social media and in professional photos. The Bureau and VICE World News couldn’t identify the source of most of the photos of the characters we encountered working for Texting Factory, many of which involved explicit nudity. At least one set was from a pornographic photoshoot.

The pictures sent by the men, however, seem to be authentic. Many of the conversations we saw involved the dick pics operators are told to encourage and welcome when they log in.

“[It was the] first time I received those kinds of pictures. Because even now the Philippines is a conservative country,” Althea said of the explicit images. “But, you know, if you really need to earn money, if you have kids, you're gonna do everything.

“And after a week, it's gonna be fine. You're not gonna be disturbed anymore... My goal was to chat around 300 messages a day. So say 200 of them sending me pictures like that, you're gonna get used to that within a day or two.”

The service we investigated, Texting Factory, claims to be part of a company called Webtech Interactive Media Ltd, a website-building and digital marketing services company based in Samoa. However, there is no record of the company or its supposed company number in the island’s official register. Texting Factory also appears to be linked to another chat operator business, Remotely4U, with one operator telling us that the two had merged in around 2020.

Cloudworkers is based in Switzerland, and describes itself in the official register as an IT and tech service provider and consultancy. All of the testimonials from supposed freelancers on its website are illustrated with what appear to be stock images.

It is also difficult to work out where the messages sent by the operators end up. We were able to identify almost a dozen sites linked to Texting Factory. One, Twomance.com, was identified in training manuals but appeared inactive when we signed up. Another, Onlyflirtshere.com, was active. Payments to both sites go to a company called White Mountain Online Solutions, registered in the Netherlands. This in turn is owned by Johnson Online Marketing, also registered in the Netherlands, which describes itself as an online marketing specialist.

None of the companies mentioned in this article responded to requests for comment.

To the operators, these companies are distant employers that can withhold payment or cut off access seemingly on a whim, with little resource except largely anonymous finance departments.

“You don't know who owns the company. You don't know who you work for. You don't know who your boss is. You just get your pay,” Althea said. “They have a third-party payroll system. And then you just send emails to the payroll system. You have disputes on your pay, but not with the management.”

The unusual nature of the arrangement was not lost on some of the workers; Althea called it “shady”.

“If you're going to start a business … then why the fuck are you gonna hide, right?” she said. “You're gonna meet people even just through Zoom, you're gonna have a Skype meeting, you're gonna show yourself, you're gonna be proud. ‘I own this company, you work for me’ stuff like that. But during my stay, I don't even know a single name. Just the salary department, or the accounting department. Nothing else.”

Over our undercover shifts, we’d sent 130 messages masquerading as dozens of different women. A few days later automated emails asked us to invoice for a grand total of €7.85 - 6 cents a message. Over the next few weeks, company-wide emails pestered us to log on to earn bonuses during peak times, and invited us to fill out a satisfaction survey. One final message noted that we hadn’t filed an invoice for some weeks. No one seemed to care that I was gone. It’s a business built on selling intimacy – but to those running the show, the workers seem as interchangeable as the characters they play.

All operator names have been changed because they either still work for the platforms or did not want the nature of the work they did to be public.

Reporting team: Jasper Jackson, Niamh McIntyre and Chrissie Giles

Global Editor: James Ball

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production: Frankie Goodway

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal: RPC

Our reporting on Big Tech is funded by Open Society Foundations. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau's editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: