Our methodology

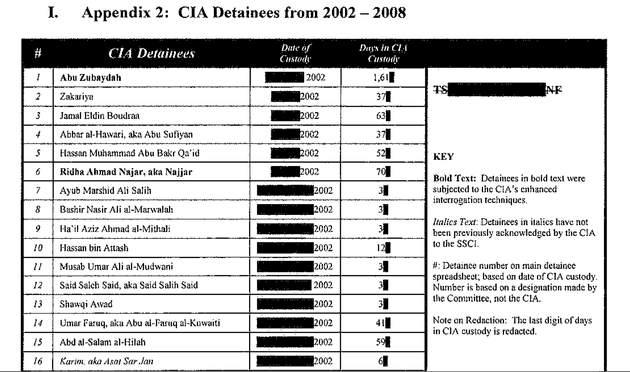

The Bureau's dataset is derived from a heavily redacted list of prisoners, published by the US Senate intelligence committee in December 2014.

Many of these individuals had never previously been named. The Bureau’s investigation in collaboration with The Rendition Project produced a dataset which provides details of what happened to each of them.

We did this through a close reading of the 500-page intelligence committee report and through correlation of the names on the list with details in other declassified government documents, legal cases, NGO reports, media reporting and flight logs.

Appendix 2, Senate intelligence committee report on CIA detention, Feb. 2015

Appendix 2, Senate intelligence committee report on CIA detention, Feb. 2015

The investigation began by attaching entry and exit dates to the 119 detainees who went through the programme - information that the CIA had redacted from the published list.

Because the list is chronological, each prisoner had to have entered the programme on the same day or after the previous prisoner, and on the same day or before the next one.

Although the report itself gives few exact dates on which particular prisoners entered the programme, it gives numerous useful indicators. These include references to when “enhanced techniques” were first practised on specific individuals, showing the date by which that prisoner had entered the programme. Where dates are redacted, the size of the redaction marks can distinguish single from double-digit numbers.

Previous investigations – by legal teams, journalists and organisations such as Reprieve, The Rendition Project, Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Open Society Justice Initiative – have given well-documented dates of transfers into, or out of, the programme in specific cases. In some instances these dates have been correlated with flight data from planes associated with the rendition programme.

In cases where testimony from released prisoners and known flight data intersects, we have used these dates as firm entry or exit points for those prisoners. In less clear cases we calculated a range of possible dates.

For the minority of prisoners who were sent to Guantánamo Bay, a date of transfer into military custody on the base is generally included in the documents hosted on the New York Times's Guantánamo Docket. This transfer date can be a useful indicator of exit date from CIA custody, but is rarely equivalent, since the majority of former CIA prisoners spent a period in military custody in Bagram before their final transfer to Guantánamo.

In some cases, the Guantánamo docket or media reporting offers firm capture dates for prisoners, but since many were captured by foreign governments or held outside the CIA programme for an initial period, this date rarely equates to a date of entry into the CIA programme. Gaps between capture date and entry date into CIA detention can indicate a period of proxy detention in other countries.

Our data was first published in January 2015, and has been updated several times since then. We anticipate a further update in the coming months.