Football’s urgent need for financial transparency

The Bureau’s revelation that Roman Abramovich appears to have spent years secretly bankrolling the Dutch club Vitesse Arnhem while he owned Chelsea could not come at a more pertinent time. Abramovich may have retreated from English football but the issues highlighted by the story remain: dual interests, sporting integrity and the question of where a club owner’s money really comes from.

As the cash continues to flow into the sport, and the era of billionaire owners makes way for a new age of nation-state takeovers, football’s urgent need for financial transparency is now being discussed at the highest levels of government.

In February, the Premier League charged Manchester City with breaching its rules on more than 100 occasions over nine years, effectively accusing the club of lying about its finances while they established themselves as the country’s leading side. City have denied wrongdoing. That came a fortnight after the Italian giants Juventus were deducted 15 points for false accounting, the board having resigned en masse in November after an investigation by public prosecutors.

The same month, the UK government presented a white paper outlining plans for a new independent regulator to oversee English football. The move would establish a test for owners and directors to ensure “enhanced due diligence on sources of wealth”.

Also in the headlines has been the multibillion-pound bid to buy Manchester United by Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad al-Thani, chair of the Qatari bank QIB. Sources close to the offer have reportedly dismissed the notion that it is effectively a state project bankrolled by Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund, which already helps to back Paris Saint-Germain – and happens to be the largest shareholder in Jassim’s bank. But the bid continues to prompt unease about dual interests in different clubs, the very issue highlighted by TBIJ’s story.

While Chelsea and Vitesse were not in direct competition as United and PSG would likely be, sporting integrity has already been brought into question: Uefa rules prevent two clubs under common ownership playing in the same competition and the former Vitesse owner Merab Jordania claimed in 2014 that the club’s efforts to win the Dutch title the previous year had been stymied because “London didn’t want that”. (Both clubs denied this at the time and Jordania has since withdrawn the claim.)

The two clubs were doing regular business during this time, too, with 22 players going to Vitesse on loan from Stamford Bridge and Chelsea signing Marco van Ginkel for £8m.

Football’s financial regulators will not enjoy learning that two of Europe’s major clubs were able to keep their cash-flows so well hidden that investigations into the very issue in question failed to spot anything untoward (links between Chelsea and Vitesse were looked into on two occasions by the Dutch FA, throwing up nothing).

As the government’s white paper stated, football clubs "are community heritage assets that will outlive their owners and directors, and so it is vital that they are appropriately managed”. But without measures that demand greater financial transparency, football leaves itself hostage to super-rich investors who may not want to play by the rules.

Chelsea and Manchester City can at least argue that their moneyed owners brought success on the pitch. But promising takeovers do not always lead to trophies and glory – just ask fans of Macclesfield and Bury, whose clubs were run into the ground by financial mismanagement. Ask the Manchester City and Newcastle supporters who believe their clubs have sold off a vital part of their identity in exchange for extraordinary wealth. Or ask the Vitesse fans who have just discovered that their club spent years being secretly bankrolled by an oligarch who owned a better-funded club abroad.

In the loosely regulated world of European club football, the downsides of unwelcome ownership can be many. But whatever they are, it is invariably the club’s paying fans rather than its super-rich owners who are left to suffer.

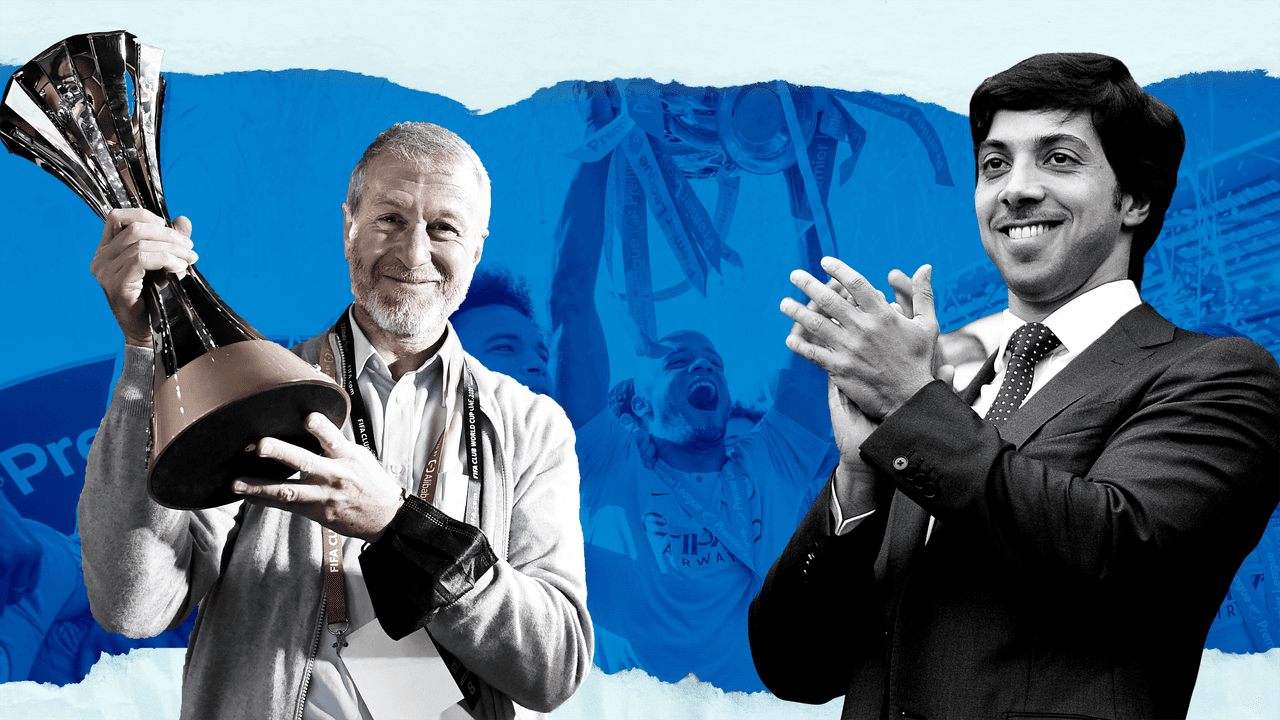

Header image: Former Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich and Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the owner of Manchester City.

Reporter: Alex Hess

Finance editor: Franz Wild

Impact Producer: Lucy Nash

Global editor: James Ball

Bureau editor: Meirion Jones

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations, the Hollick Family Foundation and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.