Disposable nappies and pop music come to South Waziristan as civilians return

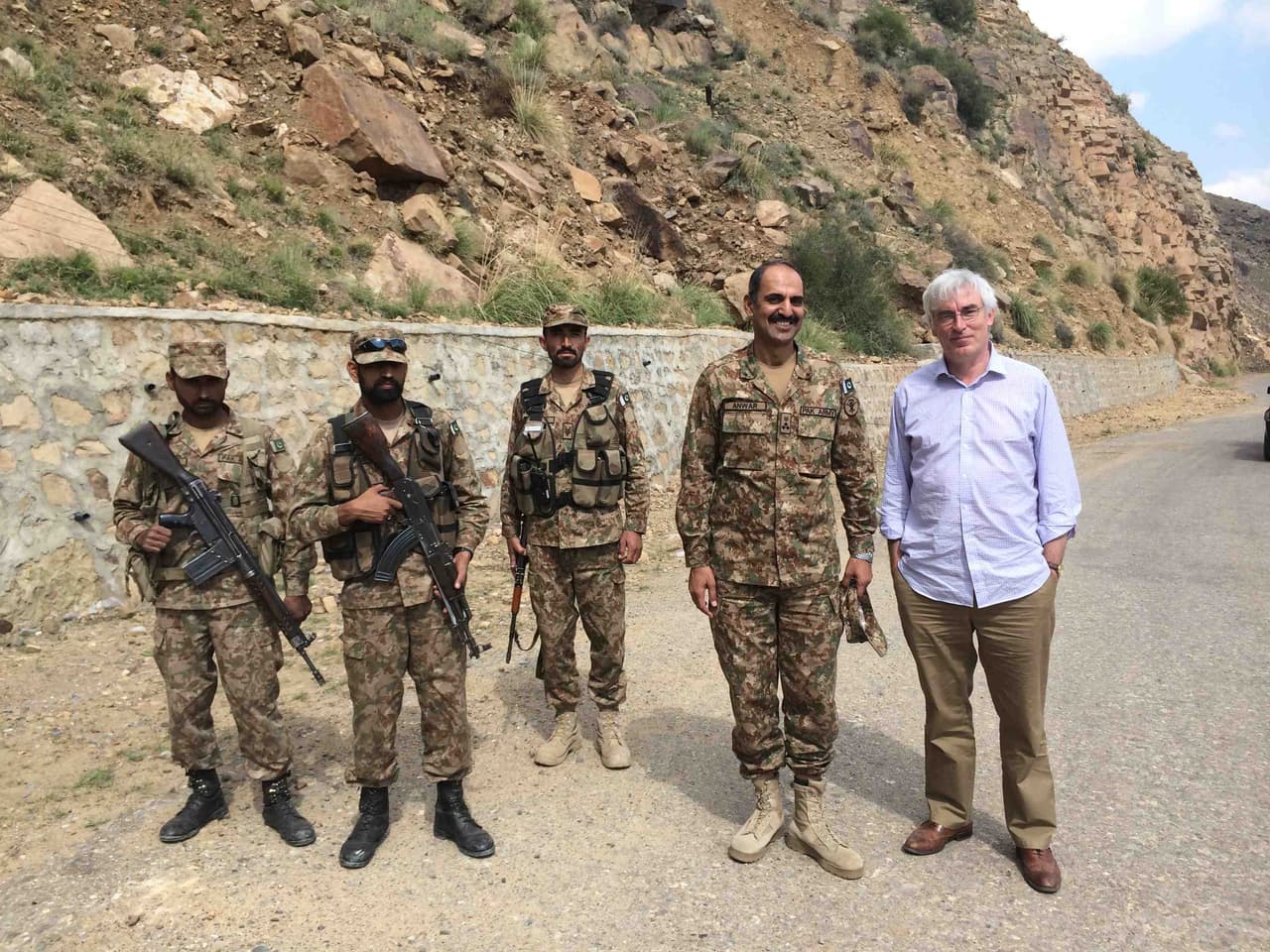

Owen Bennett Jones in South Waziristan with his military escorts. (Image: Owen Bennett Jones)

US-operated drones have been attacking the tribal areas of Pakistan since 2004. As recorded by the Bureau there have been 383 reported strikes, with 332 under President Obama. The tribal regions, an area about the size of Belgium, have largely been out of reach to journalists, particularly foreign journalists, not only because of the drone strikes, but because the area has been particularly insecure and dangerous.

While this is still true of North Waziristan, communities are starting to return to the neighbouring agency of South Waziristan, which has now largely been cleared of militants by the Pakistan military.

Owen Bennett Jones went to see how successful this has been. He reports from South Waziristan on the border with Afghanistan where he was travelling with Pakistan military

Since 9/11 the residents of the remote terrain of South Waziristan have had to cope with Taliban rule, the presence of foreign fighters from al Qaeda, a massive Pakistan army offensive and a relentless campaign of US drone strikes. The disruption to normal life could hardly have been greater and in 2009 the entire population was told to move out of the area whilst the Pakistan army fought the Taliban.

The area was emptied. Virtually the entire 450,000 residents found temporary homes elsewhere – some with relatives in other areas of Pakistan, many in temporary camps. Now, as the army has gained control of the agency, about half the original population has returned home.

Those who have stayed away include many of the wealthier South Waziristan residents who moved to Pakistan’s big cities. Many of these families – which traditionally provide the tribal elders or Maliks – are considering making the move permanent. This combined with the Taliban practice of murdering Maliks who oppose them, means that many tribal communities now lack their traditional leaders.

The violence in the tribal areas has also had other, more surprising consequences. South Waziri women in particular have been discovering the lifestyles enjoyed by other Pakistanis. Back at home South Waziristan women are strictly controlled by their husbands, fathers and brothers and spend most of their lives hidden behind high walls and closed doors. Since moving to other parts of the country they have seen women enjoying very different lifestyles: driving cars and holding down jobs.

The men of South Waziristan consequently face previously unimaginable demands. For example, having experienced the joys of disposable nappies for the first time, some South Waziri women have told their male relatives that they expect them to be provided on a permanent basis.

Radio waves

And there are other signs of creeping Western influence. Since 2008 radical Islamist clerics in northwest Pakistan have been broadcasting on channels described locally as Radio Mullah. The preachers use mobile transmitters placed on vans or even motorbikes. By the time the authorities have worked out where a Radio Mullah signal is coming from, the transmitter has been moved to a new location.

The state is now competing with Radio Mullah. In South Waziristan, FM 96 offers a mix of relationship advice, western rock and liberal religious programming.

‘Mullah Radio had stations giving messages of jihad and terrorism so we give much better content,’ said FM 96 Director Mohammed Aqib. ‘Young people want to listen to music, have fun and to know when the iPhone 5 is coming out. We give them that. And we give the correct interpretation of religion too.’

These are small changes. For those that have returned life is tough. Today the main town in South Waziristan, Wana, is still struggling to get back to normality after the army’s 2009 anti-Taliban offensive. The market place has plenty of rickety wooden stalls but only a desultory offering of vegetables and other basic commodities. There is not a woman in sight as the local men do the family shopping with elaborate, starched turbans perched high above their heads.

The army is also still very much in sight. Across South Waziristan there are more than 50,000 security personnel for just 250,000 residents.

Foreigners are not allowed into South Waziristan without official permission. And even with this permission, for foreigners to move without heavy protection would be to risk being kidnapped or worse. The Pakistan army provided me and another journalist with a helicopter and several truck-loads of heavily armed men as we moved around the area.

Wana is home to a heavily fortified Pakistan army base and a British era cantonment that houses the Frontier Corps. In an attempt to show that Wana is increasingly secure, the Pakistani General in charge of South Waziristan, Nadeem Raza, recently went on a walkabout chatting to some of the traders. When we asked to visit the market we were driven through but not allowed out of the vehicles.

This has always been a difficult area to live in. Outside of the dusty towns South Waziristan consists of desolate, mountainous, arid land. Some of the steep-sided remote valleys have virtually nothing growing and no one living in them. The houses that do exist have high mud walls and gun towers with built-in slits and holes so that the householder can defend his family from attack. Locals say that the gun towers are considered so important that most people construct them before they build their bedrooms.

Counting the dead

The army says violence in South Waziristan is declining. According to military figures, 53 soldiers and 73 Taliban were killed there in 2013 compared to 146 soldiers and 209 Taliban in 2009. So far this year 4 soldiers have been killed although many more have lost limbs because of improvised explosive devices (IEDs). There were 43 IED attacks in 2013 and there have been 17 so far this year.

The military acknowledge that there are still Taliban elements in South Waziristan. Most slip in from the neighbouring tribal agency of North Waziristan where an estimated 25,000 militants control large amounts of territory. There has, so far, been no army offensive in North Waziristan.

Bands of Taliban fighters sometimes occupy abandoned villages in South Waziristan using them as bases from which they mount attacks on security personnel. Anticipating a possible army offensive in North Waziristan, the militants are also trying to secure safe havens in the South. It leaves the residents of Wana caught between the Taliban asking for sanctuaries and the army insisting that all such requests should be denied. ‘So far, though contacts were made, the Taliban were simiply refused by the people of South Waziristan,’ says General Nadeem Raza.

Senior government officials in Islamabad say that an army campaign to clear the militants from North Waziristan would only take a couple of weeks but warn that the consequences would be grave. ‘The backlash would be felt in bomb attacks in all our big cities,’ said one cabinet minister. ‘The intelligence agencies can’t cope.’

At the start of 2014 the US agreed to stop drone strikes in Pakistan partly because the government in Islamabad asked for a pause during its dialogue with the Taliban. The killing of the Taliban leader Hakimullah Mehsud in a November 2013 drone strike led to an earlier round of talks being called off.

The lack of drone strikes is a significant change for South Waziristan. Between 2004 and 2014 there were 383 drone strikes in Pakistan as a whole. Eighty-eight of them were in South Waziristan where they killed as many as 936 people of whom up to 155 were reported to be civilians.

Speaking off the record senior Pakistani military officers fighting the Taliban in South Waziristan and other parts of north west Pakistan say the lack of drone strikes is helping them. They say that even if the drones sometimes killed senior Taliban leaders, the fact that the US is no longer using them has taken away one the jihadis’ main arguments: that the infidel US imperialists are killing Muslim civilians.

It’s a view shared by opposition politician Imran Khan. ‘The Taliban’s main issue is the drone attacks,’ he says. ‘Once the Americans go the frenzy of fanaticism in the tribal areas will start subsiding.’

In the past the Pakistan military has supported the drone programme. Up until 2011 armed US drones were launched from an airfield inside Pakistan. Deteriorating relations between Islamabad and Washington led to the US being denied access to the base. But drone strikes continued, operating instead from Afghanistan, but to growing internal opposition. In South Waziristan strikes through the last two years have been few. Eleven of the 77 drone strikes in the tribal areas since January 2012, have hit South Waziristan, killing at least 44 people, but none of them reportedly civilians. The last strike to hit the area was more than a year ago on April 17 last year.

As the peace talks got under way the strikes stopped altogether across the entire tribal areas – there has not been a reported attack since December 25, 2013.

Back in the tightly controlled Pakistan military bases the talk is now of a full blown military campaign in North Waziristan. The soldiers say they will defeat the ‘Pakistan’ Taliban but they know that any offensive will be bloody and involve significant loss of life for both side.