Learning from Pakistan and the politics of revenge

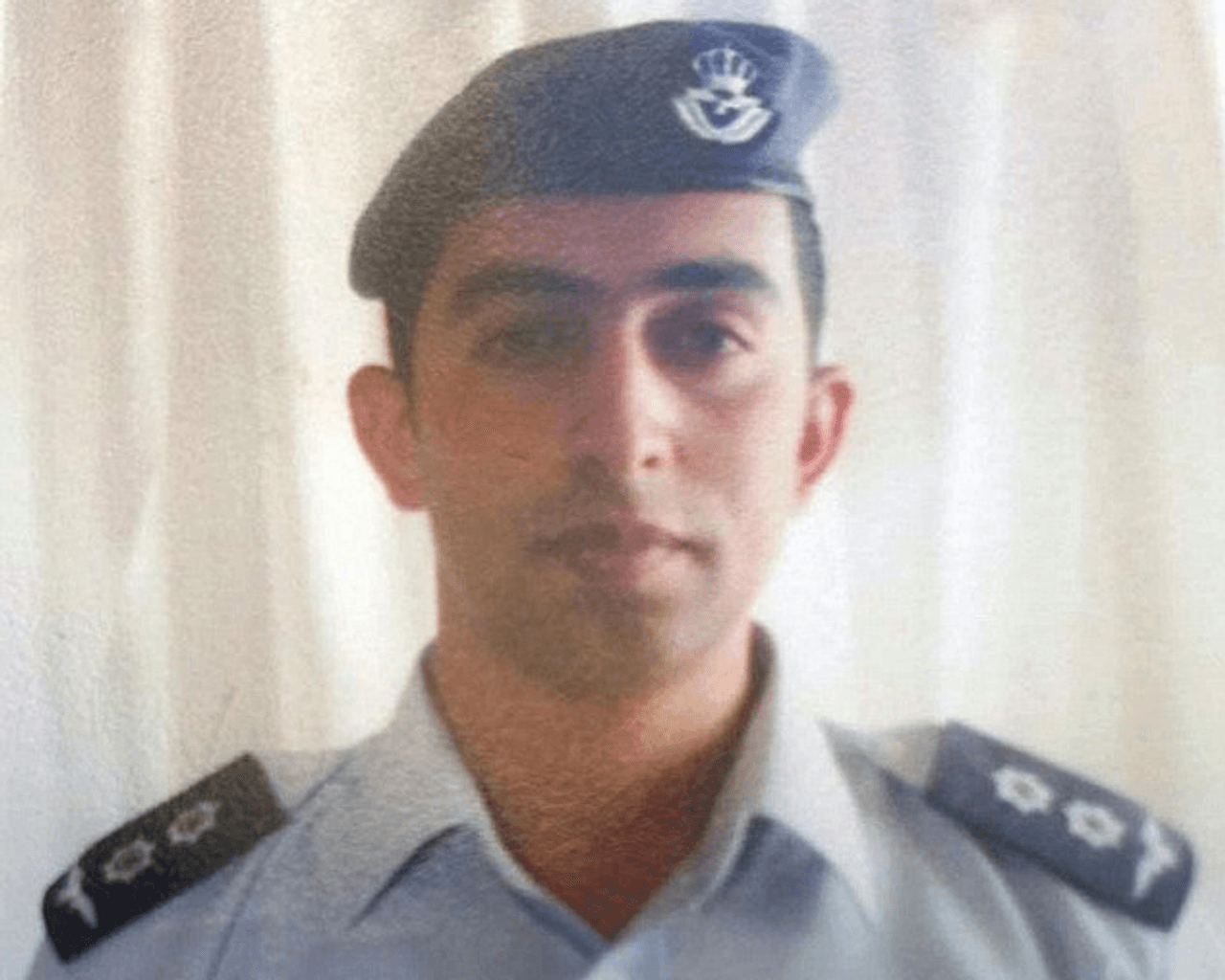

Jordanian pilot Lieutenant Moaz al-Kasasbeh

Jordan’s revenge was swift. Within 24 hours of the release of the video showing pilot Moaz al-Kasasbeh being burned alive, Amman executed failed suicide bomber Sajida al-Rishawi and convicted al-Qaeda operative Ziyad Karboli.

Islamic State had earlier suggested that al-Rishawi could be part of a prisoner exchange.

After the executions came Jordanian air strikes on Islamic State targets in Syria. Having dropped their bombs some of the planes flew over the home village of the murdered pilot. As they did so Jordan’s King Abdullah was there, offering his condolences to the pilot’s father.

The Jordanian actions echoed a similar cycle of violence in Pakistan after December’s Peshawar school massacre in which over 130 children were shot dead.

When the Pakistan Taliban admitted responsibility for that attack it said it was an act of retaliation for the army’s military campaigns in the tribal areas. Many of the children at the military-run school were from army families.

A Taliban spokesman at the time said: “We selected the army school for the attack because the government is targeting our families and females. We want them to feel the pain.”

Within a week the Pakistan army had responded in kind. It hanged an initial group of six militants selected because they had been convicted of attacks on the military. Five had been part of various plots to assassinate General Musharraf and one had taken part on the 2009 assault on the army headquarters in Rawalpindi.

The revenge culture is not new. Taliban and Al Qaeda statements have repeatedly claimed that their attacks were avenging drone strikes. In Yemen, for example, al Qaeda linked websites said the deadly 2013 attack on Defence Ministry facilities in Sanaa was a response to drone strikes.

Similarly, the Pakistan Taliban said it would avenge the November 2013 drone strike that killed the organisation’s leader Hakimullah Mehsud. “Every drop of Hakimullah’s blood will turn into a suicide bomber,” said Azam Tariq, a Pakistani Taliban spokesman. “America and their friends shouldn’t be happy because we will take revenge for our martyr’s blood.”

In both Pakistan and Jordan relatives of the jihadis’ latest victims wanted their governments to respond by taking retaliatory action .

Safi al-Kasasbeh, the Jordanian pilot’s father, demanded that the blood of his son and of the Jordanian nation “must be avenged”. Officials were quick to endorse his view. While the government promised there would be an “earth-shattering” response, an armed forces spokesman vowed “revenge will be as huge as the loss of the Jordanians”.

It was the same story in Pakistan. When he announced three days of national mourning after the school massacre, the Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif said: “We will take revenge for each and every drop of our children’s blood that was spilled today.”

The result in both countries was that the judicial system was manipulated by government and military officials to assuage public anger. And that undermined any sense that the courts function as a reliable system for dispassionately implementing the rule of law.

Given that both Pakistan and Jordan have the death penalty, the rapidly organised hangings beg the question why the prisoners had previously been exempted from punishment. Both countries have a record of cutting deals with militants in the hope that doing so will help prevent attacks at home.

While state-sanctioned revenge hangings relieve public opinion in the short term, there is good reason to think that in the longer term Islamic State’s brutality will anyway prove counter productive.

In the days after the capture of Moaz al-Kasasbeh many Jordanians expressed scepticism about their country participating in air strikes over Syria. The release of the video showing the pilot being burned alive in a cage changed all that. Now Jordanians are more united in their unequivocal opposition to Islamic State.

The same thing happened in Pakistan. The murders of the schoolchildren in Peshawar helped persuade many Pakistanis that the Pakistan Taliban are not the Islamically pure holy warriors they claim to be.

Violent jihadis face a dilemma. To remain relevant, they need to use extreme force. Their social media campaigns have to be fed with a constant stream of ever more violent images. If they want to secure international coverage each atrocity has to be more shocking than the last.

But as the threshold for violence rises, the brutality eventually becomes so gross that it puts people off.

Al Qaeda had the same problem during the American occupation of Iraq. Its affiliate in the country, under the leadership of Abu Musab Al Zarqawi, became so violent that it became unpopular.

Faced with Islamic State’s brutality governments have a choice. They can respond in anger, exacting immediate revenge. Or they can wait as the violent jihadis’ bloodlust undermines their own cause.

Follow our drones team Owen Bennett-Jones, Abigail Fielding-Smith and Jack Serle on Twitter.

Sign up for monthly updates from the Bureau’s Covert War project, subscribe to our podcast Drone News, and follow Drone Reads on Twitter to see what our team is reading.