The ghosts that haunt post-war Iraq

The quiet click of a computer keyboard and the occasional cough from one of the onlookers who sit staring at two large television screens are the only sounds. The stark walls and basic plastic chairs provide little comfort for the people gathered. At each side of the screens sit two young men facing each other. But they look straight ahead at their computers, from which they control the slideshow.

Beside them pictures are projected on the screens towards the half dozen people who focus on the mutilated bodies that flash past. It’s set up like this so the operators don’t have to look at the same startled and tortured faces every day. Occasionally, one will turn and stare mesmerized for several minutes, before seemingly catching themselves and turning away to look at anything but the grisly images of anonymous corpses that fill the screens.

It’s mid-morning and the temperature outside is already climbing into the 40s. Everyone here has spent up to two hours edging through the traffic snarls created by the endless network of military roadblocks and security bottlenecks. Once inside the cool hospital corridors they have shuffled down a long narrow hall to a double door above which hangs a small sign in Arabic – “Missing Room”.

Inside the small room air-conditioners struggle to cool the hot air but do little to break the heated tensions that hang, uneasily around the room. These people have come in search of relatives, not yet officially dead, but ‘missing’. They have come here to stare death in its face, in the hope it will bring an answer.

The Missing Room

The Missing Room in the central Baghdad hospital provides a screen-show of thousands of unidentified bodies. Many of them were mutilated before being dumped in the streets of Iraq during the occupation. In the worst days of the upsurge in sectarian violence between 2005 and 2007, the morgue would add dozens of pictures a day to this macabre show. Today perhaps one or two new pictures are added each week.

Two women sit motionless on a bench, their faces a taunt mix of concentration and horror, their eyes fixed unmoving straight ahead. They are focused on the small screen just a few feet away.

‘It’s him, it’s him,’ cries one, pointing at the screen. The attendant freezes the image on body number 10,006 so they can take a closer look. But then she’s not so sure. Her husband had lighter skin and she can’t really make out the man’s face, hideously mangled and bloodied from what looks like a bullet to the head.

‘No,’ she sighs, ‘it’s not him. Please continue.’

Athraa Mohammed and her sister Haifa resume their concentrated stares at the ghastly parade of corpses – each murdered man, tortured woman, muddied corpse and dead child staring out from the screen with looks of surprise, horror or even the occasional expression of odd peace. Many are too ripped apart or decomposed to tell who they might have been.

The two sisters are looking for Athraa’s husband, Khuthayer Abbass, a lawyer who went missing in 2006 when he was taken from a Baghdad cafe by a group of armed men, leaving his wife and two young children.

Athraa’s 13-year-old son Yasser and her 10-year-old daughter Bessam have developed critical eye problems they are told need surgery. The problems could lead to permanent eye damage or even loss of their sight. But the special treatment they need is not available in the chaos of post-war Iraq. For this they need to travel to Jordan, Lebanon or even Syria.

In video: The story of Iraq’s missing

But there is a problem. The Interior Ministry will not issue passports for the children without their father’s signature – or an official death certificate. But without a body, there is no such certificate. So the sisters come here every few weeks to look through the catalogue of bodies to see if they can find him.

‘What can we do, God have Mercy on his soul, but we still have to raise the children,’ says Haifa.

Untold grief

A few feet away huddled under a black chadour is 65-year-old Umm Ahmad. Her son, Ahmaad, went missing in late 2007. She is sitting statue-still with her younger son, Eiyad Sa’id.

‘We looked for him. We searched everywhere,’ Eiyad says. ‘But we have found nothing. We don’t know if he is in prison or even in which prison. We checked everywhere but we can’t find him. We’ve been told that he was taken by the Americans. We have asked in many police stations and no one can tell us where he is.’

For the past three and a half years they have been visiting the Missing Room. They come frequently and scrutinize the images, looking, hoping, praying that one day the face of Ahmaad will stare out at them from the screens.

Abu Essebe, Chief gravedigger, Najaf cemetary

Like many Iraqi women of her age, you get the sense Umm has led a hard, dedicated and sheltered life behind the walls of her compound and the protection of her men. But now her watery eyes stare at the slideshow of horror. It’s as if she is watching the history of occupation of Iraq – told through each individual unsolved murder. She holds a handkerchief to her mouth but must keep watching in case she misses her lost son’s face. She has viewed every photo, stared at every twisted horror. She has had moments of hope. But her dead son’s face has never appeared.

‘I have diabetes and blood pressure. But we were told that they had new pictures. I have seen them all but I thought maybe there was something new. I have tried everything, gone to wherever people suggest and to every single fortune-teller I hear of!’ She starts crying then motions towards the screens still showing picture after picture of the murdered.

‘All in the hands of God…all these young men…,’ she says, crying into the handkerchief that now covers her eyes.

Majhoul: ‘unknown’

The pictures flick past. Each one is identified by a number and the words majhoul, ‘unknown’.

Dr. Munjid Al-Rezali is the Director General of the Medical Legal Institute, which controls the Missing Room tells me the actual number of the photos on the database is confidential but that: ‘Those who went missing [in Baghdad] during the sectarian violence between 2005 and 2007 were about 30,000 – 40,000. The corpses of many of those have been brought to the institute here. I wouldn’t call them missing but rather unidentified.’

I stand at the back of the room. It feels awkward, like I am intruding on something that should only be witnessed by the closest of relatives. I try not to stare at the pictures but once you look it is somehow hard to look away. I become transfixed.

It’s the expressions. Each one is different. Each one seems frozen at the exact moment they are trying to say something. Number 9,065 is a woman looking up at the sky with an expression of sublime calm that seems odd to me because at that moment she was obviously murdered.

Number 12,568 is a man with half a face whose remaining eye peers accusingly straight into the camera; number 13,004, a child with the look of shocked surprise, his hair standing on end as if from a blast, then another man who seems to look slightly off camera in angry defiance. Many are just mangled wrecks that once were faces. Most photos were taken in haste. Few show any signs of respect. Some are naked, or just partly clothed. In one there is a 7Up can next to the body.

My gaze is suddenly broken by a loud boom. The walls and windows shake violently, a strong puff of wind blows through the curtains. The crackle of small arms fire can be heard a few blocks away. For a moment everyone in the room freezes, looking up and out of the windows, seemingly waiting for the next blast. It doesn’t come.

The attendants resume the slideshow. The onlookers return to the screen, as if nothing has happened, undaunted by the reality of the chaos outside.

This is what life in Iraq has become – a life defined by death. A life were people are immune not only to the daily bombs that still endanger their streets, but also to the horrors of the images of the thousands of unidentified bodies held on the database kept in this room.

Iraq Missing Campaign

The coffee cups, rows of files and carefully framed pictures of film posters and awards are a long way from the brutality of the Missing Room. Yet this small, neat office in central Leeds houses the only organisation in the world actively campaigning for help for the millions of Iraqis searching for their lost relatives.

It is run by 31-year old Isabelle Stead. She is sitting at a rectangular desk covered in documents, budgets and photographs spread out in front of her oversized Apple computer.

‘Not knowing the fate of a missing loved one has been classified as a form of torture by international humanitarian laws. Millions of lives in Iraq have been torn apart by this suffering. The identification and commemoration of those who have fallen as a result of war and genocide has been proven through history to be a crucial element of post-conflict reconciliation.’

Last year Stead produced an award-winning film ‘Sons of Babylon’, about an Iraqi woman’s search for her son who went missing under Saddam. In the middle of making the film, in September 2009, the film’s director, Mohamed Al-Darandji took a call from his sister, Zainab, in Baghdad. Her husband, Hassan, had traveled north on a business trip. He had not returned. They have not heard from him since.

The family has no idea if it was Al-Qaeda or Iraqi soldiers on an operation in the area at the time. But it doesn’t really matter who took him – they just want to know what happened, a longing made all the more raw as within days of her husband going missing, Mohamed’s sister discovered she was pregnant with their sixth child.

‘My sister is very strong in front of her children but as soon as her children are not around her she collapses. It’s too much for her to handle. There is no one to look after the families of the missing. There is no government or institution or organisation to deal with it. The people don’t know where to go, they don’t know where to face,’ says Mohamed.

It’s not just about the mourning process. Stead points out that most of the missing are young men between 25 and 45. This has huge social implications for a society focused on male authority, where it is rare for a woman to be a breadwinner, where all paperwork is in a man’s name and where a woman’s status is based on her marital position.

The scale of the missing

The numbers of people missing in Iraq is astounding. Under the West’s occupation estimates suggest well over 100,000 people went missing, many during the violent insurgency and sectarian killings between Sunni and Shia Iraqis that paralysed the country between 2005 and 2007.

But Iraq has history. Under Saddam Hussein hundreds of thousands, if not millions of young men ‘disappeared’. It was one of the justifications used by Tony Blair for his occupation of Iraq, after USAID announced in 2004 that 270 mass graves had been discovered, containing over 400,000 bodies. That number has now reached 360, each one containing thousands of unidentified skeletons.

Some estimates suggest there could be as many as 4 million people who have gone missing over the past three decades, and that up to 40 percent of the population have a missing relative or know someone who has. What is clear is that Iraq has the most ‘disappeared’ persons in the world.

Nothing ever happens quickly in Iraq. Stead explains her frustrated weeks trying to get figures for her film. It took weeks of telephone calls just to get to the right person only to be told that they did not have the answer. But even international organisations proved just as in the dark.

‘One of the motivating factors for developing the Iraq’s Missing Campaign was the realisation that no fully verified figures concerning the country’s missing people existed.’

Stead shows me some of the material she has collected – documents, photographs, countless letters to Iraqi and international organisations trying to get answers on the number of the missing, and trying to get someone, somewhere to do something. One main focus of her campaign is to get some action from the UN, the UK and US governments. Most of her appeals have led to nothing. ‘It’s as if they are all just washing their hands of it when Iraq needs help to solve something we have created,’ she says.

Our troops finally left the country in entirety in May. And America is scheduled to withdraw all its troops by the end of the year. Operations are being handed over to the Iraqi authorities. But until Iraq can bury its many dead, it is hard for the country to move on. This need was recognised in Bosnia by the international community. After the conflict the International Commission on Missing Persons (ICMP), was established, with major White House support under Bill Clinton, to assist in uncovering mass hidden graves and identify missing people.

Through DNA technology and forensic science, the ICMP has developed a database of 88,610 relatives of 29,073 missing people. The ICMP has now assisted in resolving approximately 20,000 cases and has made more than 12,000 DNA-led identifications.

In Iraq sectarian and political differences between the various factions making up government is one of the main barriers to any real progress. Put simply – if they are Kurd of Sunni they will have a different view on whether to investigate Kurd disappearances, if someone was in the former Ba’athist they resist investigating disappearances under Saddam, if they are Shia or Sunni they don’t want to investigate militia killings during the height of the sectarian killings.

The Iraqi Government has taken one small step in the right direction. Those with missing people can now go to the army headquarters in the area where they think their relative went missing and register.

It’s a start, but there is still so much more that the government and perhaps more importantly the international community could do. It takes three weeks for me to track down the Iraq representative for the ICMP, although he does eventually send me as much information as he can. He says they are starting to train some Iraqis in DNA testing and the basics of body identification.

It has taken them months to get the Iraqi government close to signing an agreement, which could significantly boost the ICMP’s training and help for the missing by centralising the process. But even then much of this work is focused on the mass graves from Saddam’s rule and seems to avoid the politically sensitive deaths that occurred under the coalition occupation after 2003.

‘People can never be at peace. They can never grieve until they have a body. And if somebody can’t grieve there is an on-going issue with anger. Everyone is unsettled. The nation is unsettled and if we want to rebuild the nation, we have to first clean the wound,’ says Stead looking at a handwritten letter.

In video: Deputy Editor Rachel Oldroyd explains why the Bureau has followed this story

Among her documents are a growing number of such letters and emails all from people desperately asking if she might have any information about their missing relative – or even worse – if she can help find them.

‘Today I have to reply to an email from a woman asking if I can find her brother. She’s desperate, but I have to tell her that we are not that type of an organisation. We are the closest thing to it, but that’s how ridiculous it is, that filmmakers are taking the shoes of what the international community should be doing. I wish I knew more. I wish I had more resources. I can’t give this woman an answer.’

Even in the Baghdad morgue, where the photographic database is the only major project helping the country find its dead, the process is painstakingly slow. People come day after day, month after month, but the majority do not find the resolution they seek.

Perhaps the bodies are too decomposed, or too tortured to make the identification. Perhaps they were just never found.

Sectarian violence

During the occupation, the 93 miles from Baghdad to Najaf were notoriously treacherous. Kidnappings and killings were a daily occurrence on the dual carriageway road. Even today, the way from the capital to the main city in the South is still hazardous. We travel in escort, in two American sedans that have been fitted with low-key bullet-proof sides. The main security vehicle travels in front. I am in the back car with a translator. In front, our main bodyguard has a handgun under his shirt and an AK-47 automatic rifle on the floor under a blanket. They call this ‘low profile’, more suited now officially the Iraqi military is in charge of security. Before setting off we have been through a series of strict security protocols and we each carry our mobile phones in our hand ready to key in and send the four-digit code that will alert our main security contact in Baghdad if we find ourselves in any danger.

We leave before dawn to avoid the intense heat that bakes the desert through which the road passes. The war is over, but the burnt-out carcasses of car bombs and even the odd tank that still litter the edges of this main artery make it hard to believe this war-torn country is at peace. Some areas of Baghdad and roads just north of the capital are still ‘high kidnap risk’ zones, uncontrolled by police or army.

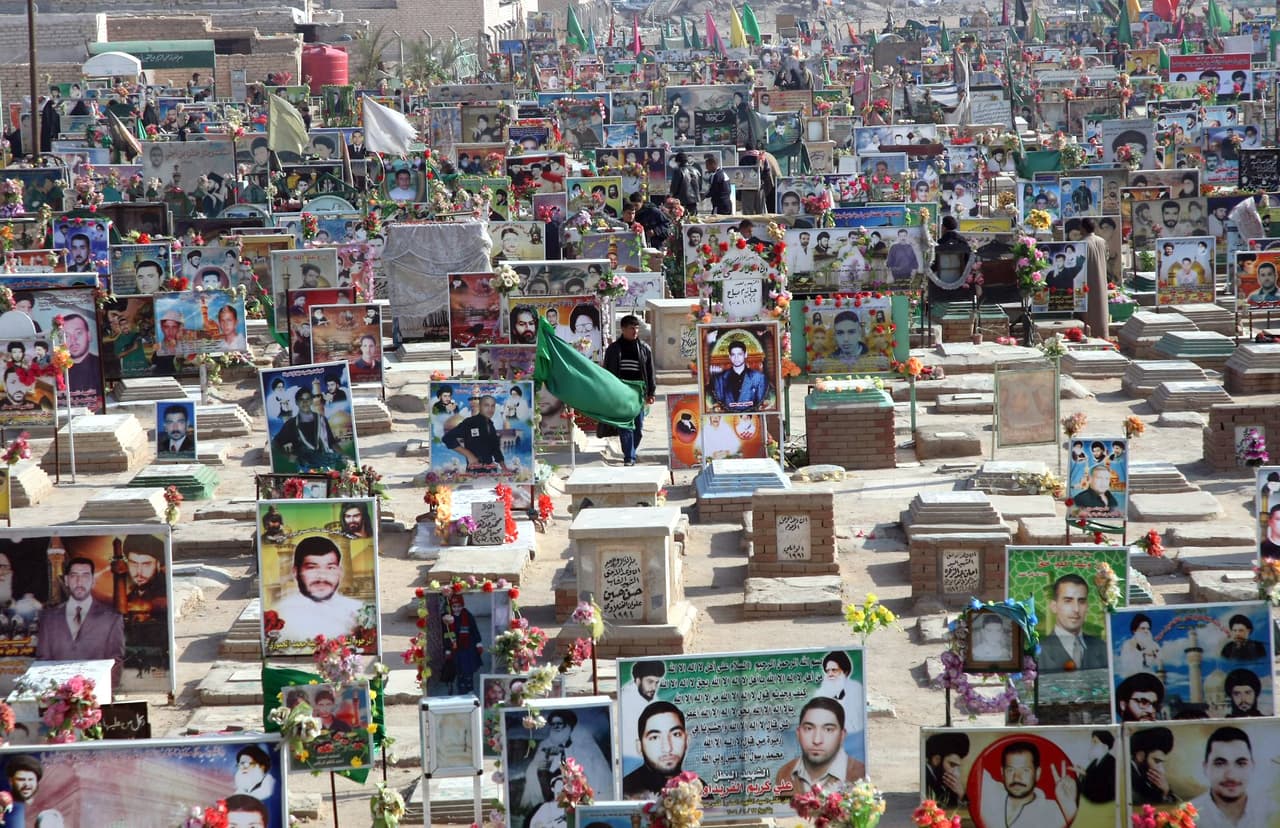

Najaf is the spiritual capital of Shiite Islam. For more than a millennium, the deceased have been taken to its cemetery, the Valley of Peace, to be buried by the golden-domed tomb of Imam Ali, the revered Shiite saint. We arrive at about 11am, as the sun starts to heat up the sandy yellow earth.

Tomb after tomb, gravestone after gravestone packed in, some on top of each other, stretch as far as the eye can see. This is the city of the dead, the biggest cemetery in the world, with an estimated 5m Shiite muslims laid to rest.

During the occupation the Valley of Peace received thousands of the unidentified corpses, each buried in a corner of this sprawling citadel, Sunni and Shia placed together, unknown.

I am taken inside by Haji Bayan Shaker Abu Essebe, the chief gravedigger, whose family has been in charge of the cemetery for hundreds of years.

There are all types of graves here, some ornate mausoleums and others small brick structures, all appear well tended and much loved. But on the edges of the sprawl, Haji Bayan has led me to an area littered with small concrete plaques.

‘These are what we call the unknown,’ he says, pointing to the rows of slabs, each inscribed with the elegant calligraphy of Arabic denoting a number and a date. There are several thousand in this area alone, with many more in other parts of the cemetery.

‘A truck would come from the morgue in Baghdad,’ he tells me. ‘Sometimes it would bring fifty bodies sometimes it would bring 70, it depended on the incidents that happened. At times there were between 150 and 200 bodies a month. At the worse times, on one day there were two hundred, sometimes above 200.’

Most of these ‘unknown’ bodies have a number. The number is recorded against a photograph, all held on the database in the Missing Room in Baghdad.

Mohammed Abdeljebbar, 36, was lucky. He recognised his brother in the photos held in Baghdad. His brother’s face was disfigured. A bullet, or possibly a shell had blown part of it up. But Mohammed knew it was his brother instantly.

‘I shouted ‘This is my brother. This is my brother.’

Mohammed was given a number and sent to the morgue, where the body was still being held. ‘They brought a body and said ‘This is Motezz.’ but I said: No, it’s not him. I saw the photo and he doesn’t look like him.’ Then they brought another body and said ‘This is Motezz.’ and again I said it wasn’t him. Even my father and uncle who were with me asked: ‘Are you sure you saw his photo?’ But when they brought the third body, I recognized Motezz. My brother.’

Most of the people who find a lost one are directed here to Najaf. Only Haji Bayan can take you then to the place where the body rests. In a red leather book he keeps a hand-drawn map, on which each grave is marked, with a careful note of its number.

Haji Bayan gestures at the stones. ‘The people they come to the one with the same number, they come and open the grave. Some of the bodies were buried with clothes, so the family can recognise him, from his clothes. If the body had any ‘Mustamsek’ (document), they put it next to him too.

‘They open the grave and look at the body. They see the details inside, if he belongs to them, they re-bury him, or dig another tomb, or build a memorial. If it turns out that it’s not their son, the body is returned to the same place.’

‘It’s very hard, it’s very hard. Some people come here and start wailing. Some lose consciousness. Some don’t know what to do with themselves. You know my friend, children are dear…children are very dear…’

Haji Bayan’s face reflects some of the pain he has witnessed from the families who have come and found their lost relative. But for many in Iraq this is but a hoped-for dream. Mohammed Abdeljebbar is considered one of the lucky ones. He has been able to end his search, to bury his brother, to mourn and move on. But many are still searching.

‘I am afraid it will be one of the issues that makes Iraq still not a safe place. The brother of my sister’s husband, the one that went missing is very angry. He would like to take revenge. But he doesn’t know who the enemy is. So he can direct his anger against everyone – against American, against the Iraqi army, against al-Qaeda, the sunni, against everything, says film director Mohamed

Six months after returning from Iraq I met Isabelle and Mohamed. I felt the need to know whether any of the people I had met in the Missing Room had found their lost loved-ones. I wanted to know whether they had been able to take their number to Najaf and retrieve the remains of the son, the brother, or the husband who had left them so many years before. Over a month we were able to track down some of the people we had spoken to. But none of them had found the body. They were all still searching, all still living a suspended life, waiting for the day when they could move on

This piece is published in the Mail on Sunday: One British woman and the agonising search for the missing millions in Iraq