Olympus whistleblower tells all

‘If you’re the nail that sticks out, you get hammered down,’ says a Japanese proverb (Image via NipponNews)

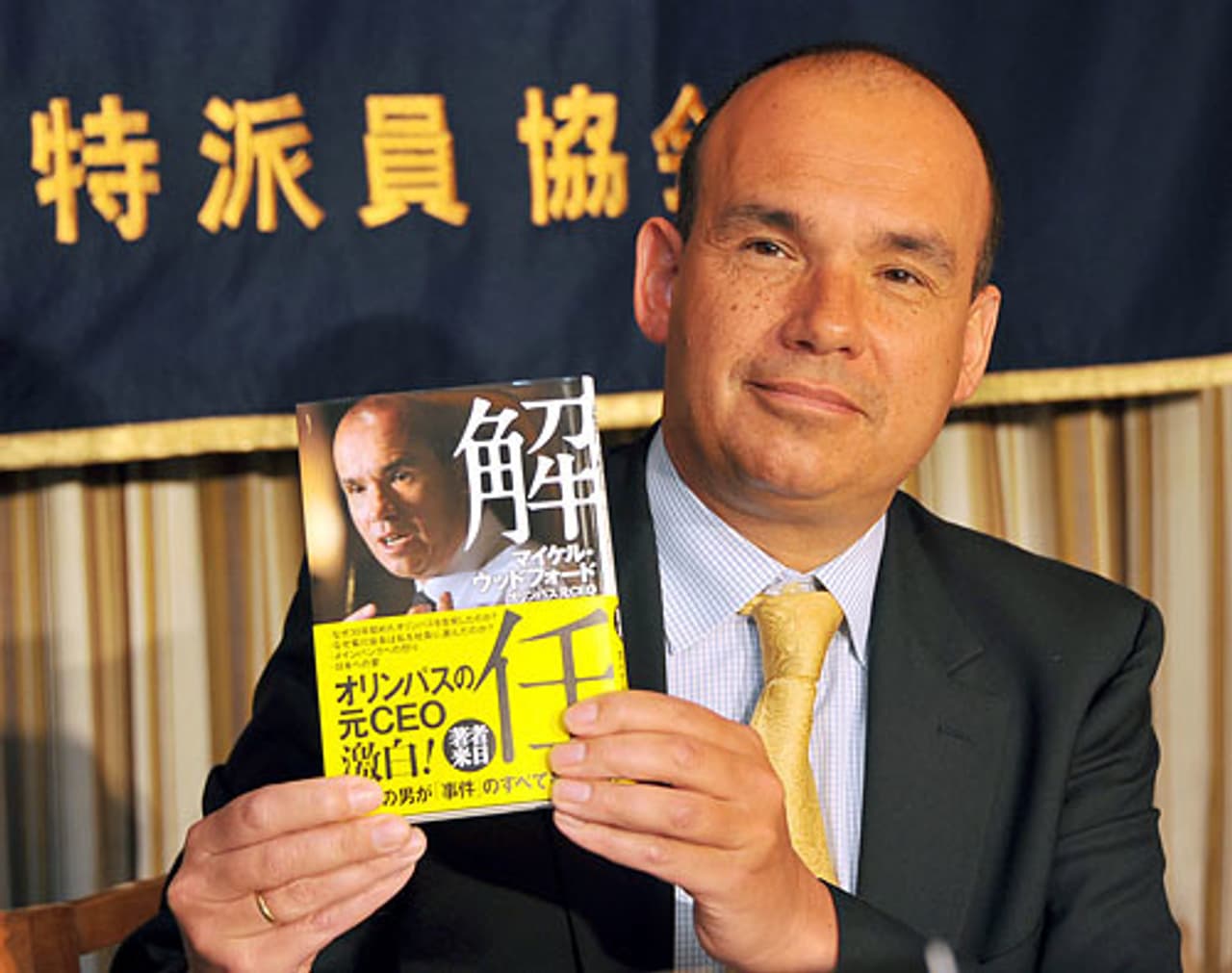

Michael Woodford, the former British CEO who in 2011 exposed massive internal fraud within the Japanese corporate giant that employed him, didn’t see himself as a whistleblower. In many ways, he still doesn’t.

When he was appointed president of Olympus, in early 2011, he was expecting long working days and a steady stream of sumptuous sushi platters. Instead, Woodford found a cover-up of multi-billion-dollar company fraud with possible links to Japan’s feared mafia, the Yakuza. His courageous actions in denouncing the fraud catapulted him to corporate and popular stardom and have given rise to a book, Exposure: Inside the Olympus Scandal. Hollywood is also on the horizon.

‘I was never sure that the term whistleblower quite described what I was,’ Woodford writes in the book, which was launched this week with a dynamic public lecture at the London School of Economics (LSE).

‘Rotten core’

Olympus, a global company of 40,000 employees, specialising in medical technology and cameras, had been home to Liverpool-born Woodford for most of his 30-year working life. After coming across allegations of billion-dollar fraud in an article in Japanese magazine Facta in July 2011, Woodford wanted to act – but was told it was not his problem. ‘You’re too busy,’ his chairman told him dismissively.

‘I was starting to realise that the road to becoming a whistleblower was a lonely one and sets you apart. You become an island.’

Michael Woodford

Related article: Olympus payout misses chance to establish whistleblower precedent

For many weeks, Woodford failed to elicit any response from his Japanese colleagues as to why Olympus had sunk nearly £2 billion into the purchase of three unprofitable and unrelated companies, including one that produced shiitake mushroom-based face cream.

Tensions grew between Woodford and his colleagues and tempers flared in the usually placid Japanese corporate environment. Despite early signs of support for his calls for an independent investigation into the fraud, Woodford was stripped of his Olympus positions in October 2011 and sent packing – just two weeks after having been promoted to CEO.

‘I was starting to realise that the road to becoming a whistleblower was a lonely one and sets you apart,’ he writes in Exposure. ‘You become an island.’

Being the whistleblower

Buoyed by the kindness of strangers and a troupe of friends and family who stuck by his side, Woodford rode out the storm that broke after his exposure. It helped that international media, politicians and celebrities knew Woodford and liked him, running with his explosive story from the start. But it wasn’t always easy – midnight phone calls from journalists and the constant fear of losing an index finger to vengeful Japanese mafia would sometimes keep Woodford and his wife awake at night.

Woodford avoids framing his story as pitting Japanese against non-Japanese. Although enemies accused him of racism and anti-Japanese sentiment. ‘[I]t’s about the reformers versus the non-reformers,’ he writes.

Woodford wanted to act but was told it was not his problem. ‘You’re too busy,’ his CEO told him dismissively

He sees the Olympus scandal as indicative of a much wider malaise within Japan’s corporate and social structures. In the context of Japan’s declining economic and political power, Woodford writes of ‘a company and a country in trouble’. He is not alone in this opinion; in July 2012 the NGO Transparency International published a report on corporate transparency measures, which found Japanese companies ‘to perform particularly poorly’.