‘I saw a big balloon of dust. Then I heard a bang’ – an eyewitness speaks

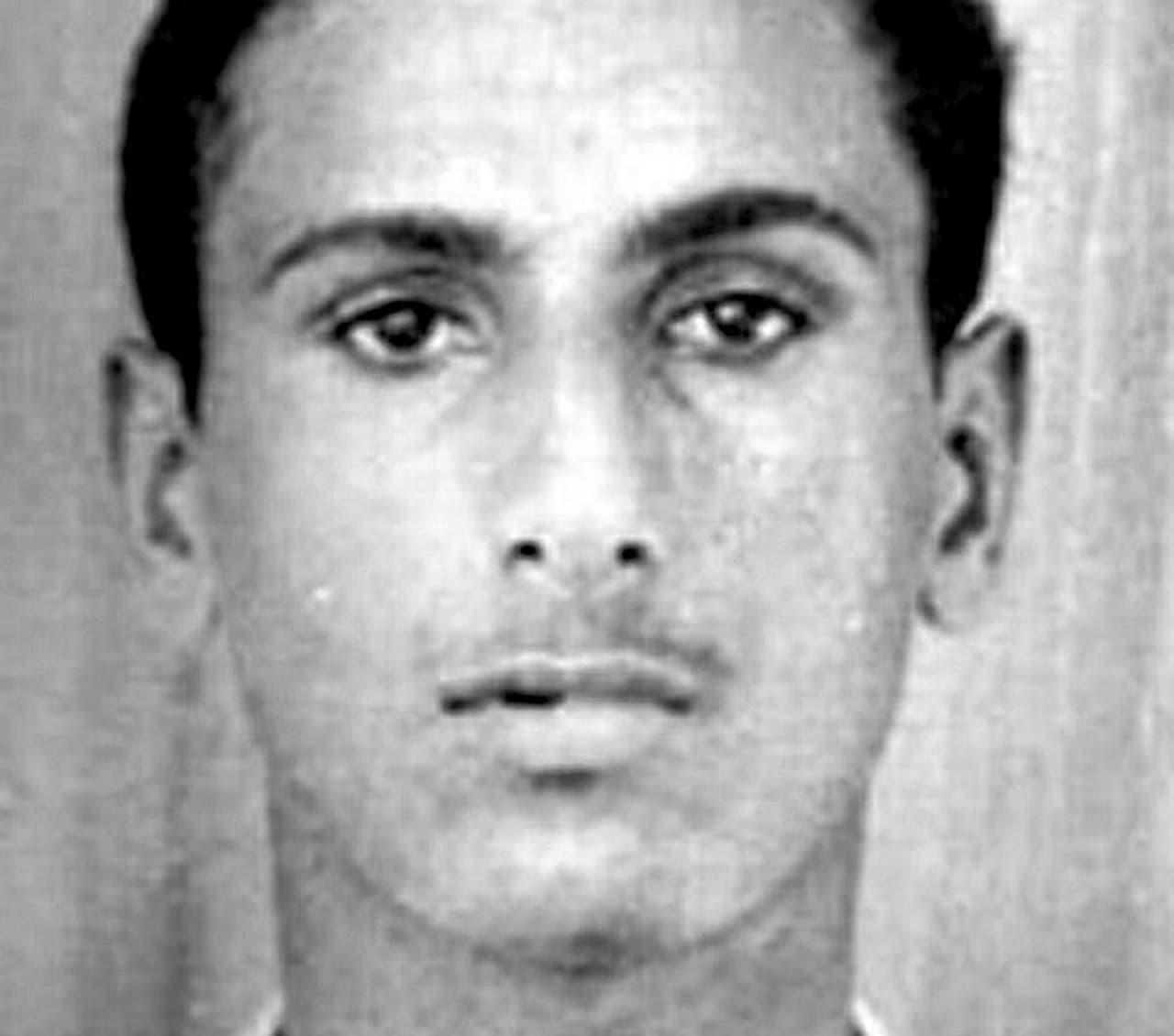

Usama al Kini – or Asmaray Khan – the terrorist whose death Noor believes he witnessed (Photo: FBI)

This story originally appeared on Naming the Dead, the Bureau’s project identifying those killed in CIA drone strikes in Pakistan

Four years after seeing the drone strike, the scene remains vivid to Noor.*

‘It was midday, maybe 2 or 3pm… I was behind my house at the top of the hill. The valley was clear to me,’ he told me, when we met during a research trip to Pakistan in late 2013.

‘I saw a big balloon of dust. Then I heard a bang,’ he said.

As he watched, a drone hovering far overhead fired a missile at a car travelling in the valley below, on the road from Shwekai to Narai, in South Waziristan, an area in Pakistan’s tribal regions bordering the Afghan border.

When the dust cleared, Noor could see that a missile had hit the front end of the vehicle – but its occupants had survived – and were making their escape. ‘I could see they couldn’t walk properly. It looked like they were injured,’ he explained.

But they were not safe for long. ‘Another drone attack occurred. In this strike, the three people were completely finished. Their bodies were pieces of bodies,’ Noor said.

Noor was the first to reach the wreckage of the car, but other locals soon joined him, curious about the attack. ‘It was near our homes, so first of all local people came and collected the bodies,’ he said.

Someone recognised the vehicle as belonging to a feared Arab commander known locally by the name of Asmaray Khan. Before long, a large group of militants – estimated by Noor to number up to 60 – came to collect the body parts of the dead men.

‘These three were militants, it’s clear,’ he said.

Related story – Government report identifies 20 people killed in Pakistan in 2009 drone strike

I have no doubt that Noor was sincere about what he described. He was extremely nervous as he told his story, his hands clasped tightly together as he told us in a low, urgent voice about the strike and about the harm the militant groups have done to his community. He was sweating despite the air-conditioning.

We gathered a number of eyewitness accounts that afternoon, and Noor’s testimony was among the most convincing and detailed. We have been unable to identify the drone strikes to which several of the other accounts refer.

Noor’s testimony is not perfect either. He described the events as taking place ‘about two years ago’ – and we could not find a strike matching that description in the winter of 2011.

Nor did we have the name of the commander he named, Asmaray Khan, in our database, and I could find no mention of him online.

But then I told a Pashtun friend about the story. She instantly recognised the name Asmaray Khan as a senior militant – Asmaray means ‘the Beast’, she explained. He was well-known far beyond the tribal regions. But this was a nickname. His real name was something else, although she couldn’t quite remember what it was.

An intelligence source was able to answer this question instantly. Asmaray Khan was the local nickname for Usama al Kini, he said.

Unlike Asmaray Khan, Usama al Kini did appear in our database. He was a Kenyan-born man who, according to reports and the US government, was a senior member of al Qaeda with a $5m bounty on his head offered by the FBI.

Read Usama al Kini’s case study

But he was reportedly killed in the final drone strike of George Bush’s presidency, which hit an abandoned girls’ school in Madin, South Waziristan, on January 1 2009. According toWashington Post reporter Joby Warrick, CIA director Michael Hayden personally intervened to demand that operators used a huge bunker-busting bomb instead of the usual Hellfire missiles, to ensure that al Kini was killed.

His ‘lieutenant’, a Kenyan named Sheikh Ahmed Salim Swedan, also died in the strike, Warrick and the New York Times reported.

Related story – Only one in five of those killed in CIA drone strikes in Pakistan have been named

This was several years before the date Noor described – and while this is perhaps understandable, it was also on a completely different target from the one Noor described. He also described seeing two missiles, not a massive bomb.

There was no way Noor’s description matched the event that many other sources say killed al Kini.

But his description does closely match an attack of the previous day, in which a drone attacked a vehicle driving in the area Noor described. A document compiled by the local tribal authorities describes how three ‘non-locals’ were killed in a strike on a ‘Peju [Peugeot] Motorcar’. News reports described the dead as ‘known Taliban militants’, although military officials said they were from Turkmenistan.

The attack is in the right time of year, and at the right time of day – both details that we believe are more likely to be accurate than recollections of the date, which are often hazy to people, particularly several years after.

It hit the right kind of target – a vehicle. At least three men did indeed die, just as Noor described. And al Kini – or Asmaray Khan – was high enough status to possibly warrant a very large contingent of men to come and collect his remains.

Did al Kini narrowly survive an attack the day before his death? Was the vehicle Noor saw targeted because it belonged to this senior target? Or did local gossip confuse the two strikes?

We don’t know – and the case indicates some of the huge potential problems in gathering eyewitness testimony. Even when it is from a credible and convincing witness, and can be cross-checked and verified with other reports of events, it may still have significant errors or misconceptions – in this case, as profound as life or death.

* Name has been changed to protect the eyewitness’ identity.