Scourge of superbugs killing Malawi’s babies

In a baking hot room in the corner of Chatinka nursery, the specialist baby ward in Blantyre’s Queen Elizabeth hospital, the Bureau found Lilian Matchaya expressing milk. Her daughter, Abigail, was lying nearby under a UV light, laid inside a wooden cot to keep her at the right temperature. Her head was wrapped in a bandage and she had a plastic feeding tube in her nose. Lilian inserted a syringe of breast milk into the tube. It travelled slowly down the translucent pipe. Around them were the sounds of infants crying, machines beeping and nurses pushing trolleys around the ward.

Abigail was born prematurely at seven months old. She weighed 1.8kg, little more than a bag of flour. She needed an injection to help her breathe. A day after birth there was blood in her stool. Nurses found her unresponsive.

Babies, especially those born prematurely, are vulnerable to infection as their immune systems haven’t developed properly. Doctors suspected Abigail had sepsis, a serious and potentially fatal condition in which bacteria enter the bloodstream. In response, the body’s immune system goes into overdrive and the organs begin to shut down.

Doctors gave Abigail two antibiotics, penicillin and gentamicin, a combination meant to kill a wide range of bacteria. The drugs didn’t seem to work so she was given others, ceftriaxone and metronidazole. But still there was no improvement. Her medical notes, which her mother allowed us to read, said she became floppy and passed out again.

Lab results taken earlier came back and revealed she was infected with a superbug called Klebsiella. It was resistant to most of the drugs she had been given; they weren’t working to kill her infection. Like so many other babies in Malawi, she had been given ineffective drugs for days because of antibiotic resistance. She remained desperately ill.

Now her doctors faced a problem. The antibiotics they needed in order to treat her resistant Klebsiella infection are expensive and not part of Malawi’s standard drug regimen. They are not always available in the hospital. Fortunately, this time the pharmacy had one of the drugs they needed: amikacin. However, it has severe side effects. It can only be given for short periods as it can trigger deafness, kidney and nerve damage.

Abigail was administered amikacin. Her family then faced a waiting game to see if she will survive. “The first thing I do when I wake up daily is to pray for my baby to get well. Then I check on her with the hope that she will be okay,” said Lilian, a soft-voiced housewife who lives with her husband, a teacher, and three sons in Nancholi, an area on the outskirts of Blantyre. As we left, she promised to text us an update on Abigail’s condition.

Battling sepsis in Malawi

An epidemic of infections across Malawi is causing sepsis. It is one of the leading causes of death among newborns, killing nearly a fifth of neonates in 2016. In the UK sepsis is responsible for less than 2% of infant deaths. The figures in Malawi are thought to be highly underestimated, as most healthcare facilities do not have the tests to diagnose it.

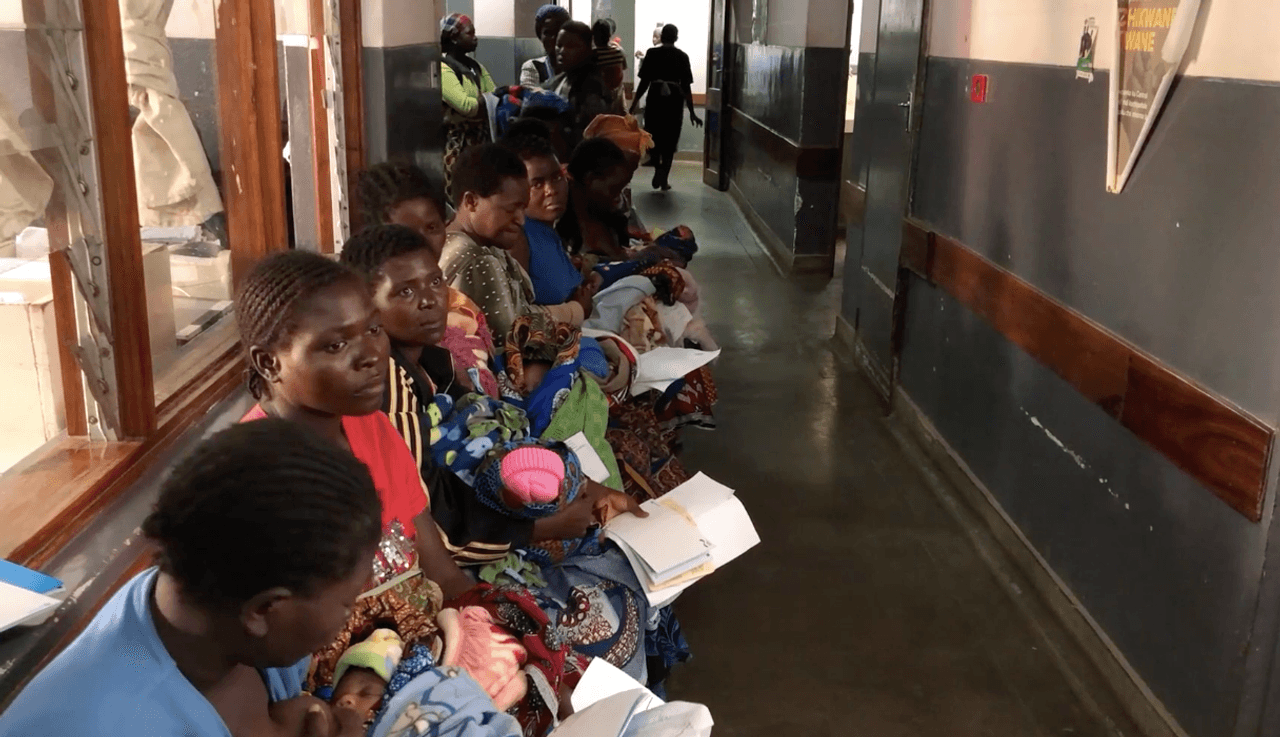

Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world. Its GDP per capita is $300 (the UK’s is more than $40,000) and is growing more slowly than other comparable African countries. In the cities you can find rich Malawians and expatriates who live comfortably, hiring maids, nannies, guards and gardeners. But the majority of Malawians are poor: more than 70% of its 18 million people survive on less than $1.90 a day, the international benchmark of poverty. In light of the economic situation, the healthcare budget is small. The World Health Organisation says that just $93 (£70) is spent per head on healthcare compared to $3,377 (£2,557) in the UK. The health system is vastly overstretched, with some NGOs declaring it to be in crisis. There is a shortage of doctors - only around 600 across the whole country - as well as other healthcare staff. In the UK one nurse would be assigned to care for every sick, newborn baby. In Malawi there can be as many as 23 babies per nurse or midwife.

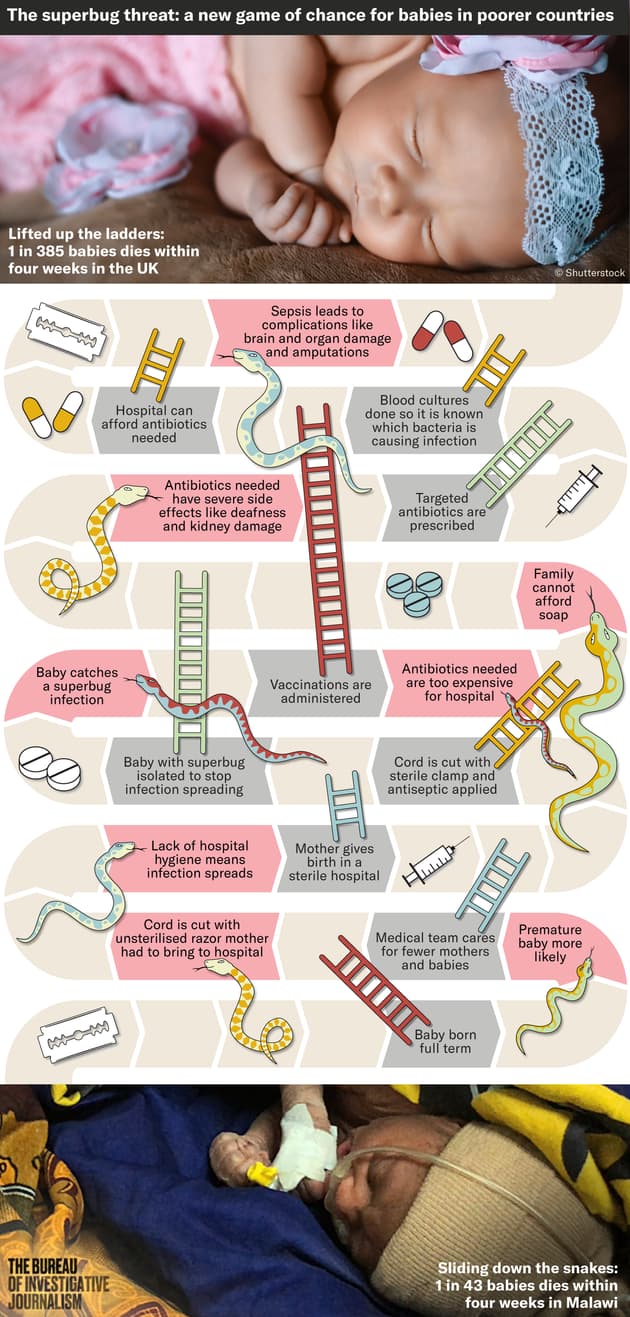

Malawi has a high rate of newborns dying (one in 43, compared to one in 385 in the UK) before they are a month old. A combination of factors, all related to poverty, mean the percentage of babies dying of sepsis has barely fallen since 2000, despite improvements in the healthcare system.

Malnutrition and a high number of diseases like HIV and malaria mean that mothers and babies’ immune systems are weaker and they catch infections that a Westerner’s body might easily quash. The majority of Malawians don’t have running water so cleaning is difficult and soap expensive. Many lack education on the importance of washing hands or how to hygienically change their baby’s nappy, prepare food, bathe or wash clothes and dishes. Not everyone can afford to go to the doctor when they become ill. Travelling there would be too expensive, there would be no one to care for the children, or it would mean time off work and no pay.

More than half of healthcare facilities are also failing to meet World Health Organisation standards on water and sanitation facilities, according to Unicef. Even Queen Elizabeth hospital, Malawi’s biggest, does not have running water in every room. During our visit we watched a doctor turn on a tap. No water came out and the tap fell off in his hand.

We visited three hospitals and two health care centres and they all reported “stockouts”, periods when supplies like soap, chlorine, bleach and sterile gloves – all important for infection prevention - run out. A three-month spike in sepsis rates from October 2017 occurred at the same time as a shortage of chlorhexidine, an antiseptic put on a baby’s cord after it has been cut to prevent infection, Wezi Kalumbu, an advisor on children for the health NGO, ONSE, told us.

Poor hygiene means there is a constant cycle of infection in Malawi, and a constant need for antibiotics, whose use fuels resistance. So experts say a new problem has emerged: the failure of drugs given to treat infections.

Controlling infection

Later, we drove down a sandy, potholed track near the border of Mozambique to Nayuchi health centre. Tamandua Chirwa, who runs the rural hospital, recalled how delighted she was the day running water was installed. Before that, it was difficult to recruit staff as there was no toilet. Buckets of water had to be carried from the nearby village’s borehole for hand washing or cleaning the hospital. Pregnant women would avoid coming to the centre because conditions were unhygienic and they believed it was safer to give birth at home. If they got an infection, even a severe one like sepsis, they would avoid coming in for fear of being reprimanded by doctors for not seeking healthcare sooner.

WaterAid installed a borehole and solar panelled water in March 2017. The rooms could now be cleaned properly. “It was very encouraging when we had water” Ms Chirwa said. “We had more women delivering at the hospital. They knew after delivery we will have safe water to clean ourselves up.”

In the same district is Nyambi healthcare centre, which has no running water. Green vats which once held rainwater from the roof now lie broken around the centre. There are five toilets but all but one have broken, meaning roughly 300 people - pregnant women, families and staff - share it.

Women are asked to bring candles or torches in case there is no power. They are also told to bring their own razor blades to cut the cord (one lies rusting on a sink next to metal kidney dishes) as well as a plastic sheet on which to give birth, called a macintosh in Malawi. Most health centres and hospitals we visit ask women to bring these supplies with them.

As we walked around, the lights went out. Electricity blackouts are common in Malawi, with midwives warning of babies dying in incubators as a result. At Nyambi the blackouts mean they cannot always sterilise equipment like forceps to use during labour. There is no incinerator for placentas.

We met two pregnant women, Ruth White and Jenifa Lyson, 23 and 24, in the cobweb-ridden waiting room, which had an non-working sink full of dried corn, and a rusty wheelchair in a corner. “This place is very unhygienic and it stinks a lot,” Jenifa said.

Ruth and Jenifa stayed here so they could be near the health centre in case their waters broke. They slept on the same black plastic sheet on which they would later give birth, risking catching an infection or passing one to their baby. Conditions were “embarrassing” said Sphiwe Kachimangha, infection prevention control lead for Machinga district. “We are in financial crisis so it is difficult to tackle all the problems at once.”

Simple measures like washing hands could prevent many infections. But for people in poverty, soap is a luxury. Buying enough for handwashing, cleaning plates and clothes costs around 3,000 kwacha (£3.30) a month said Bertha Gesinao, 19, who we met in Khambo village in the rural Chikwawa district. She and her husband, who works on a sugar cane plantation, earn 9,200 kwacha (£9.60) between them a month. “I can’t spend all my earnings on buying soap as I’m also relying on the same to buy food and other basic needs,” she told the Bureau.

Midwives also voice concerns about cultural practices around cutting the umbilical cord. Sometimes animal dung or the juice of a pumpkin flower is rubbed on the wound, which could cause infections which lead to sepsis. However, many said these practices are dying out due to education campaigns.

A patchwork of NGOs are building boreholes to give rural communities access to water. It is not in all of these organisations’ remits to check the water is safe. Save Kumwenda, senior lecturer in environmental health in the University of Malawi Polytechnic said surveys were done in Mulanje and Chikwawa districts and around 20% of the boreholes there were contaminated with fecal matter. Even in Blantyre there are areas, such as Ndirande, one of the largest slums in southern Africa, where people drink unsafe water out of shallow wells. “We are sitting on a ticking bomb,” he said, of the threat of unclean water.

Infographic design by Steven Bernard, for TBIJ

Infographic design by Steven Bernard, for TBIJ

An unhygienic environment will lead to infection and more antibiotic use, which leads to antimicrobial resistance, said Dr Nicholas Feasey, an infectious diseases researcher and microbiologist at the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Centre, the research institution next door to Queen Elizabeth hospital.

Dr Feasey and his team have tracked the rise of antibiotic resistance at the hospital as part of a major study, the only one of its scale across sub-Saharan Africa, where data on resistance remains scarce.

They analysed bacteria causing bloodstream infections in adults and children from 1998 to 2016. The good news, he reported, is that bloodstream infections fell from 2005 onwards, which overlapped with improvements in HIV and malaria care in Malawi and a fertiliser subsidy which helped people grow more food, reducing malnutrition.

But there is bad news too. More than half of infections are now resistant to the antibiotics that would be given in the first case in Malawi - penicillin, ampicillin and chloramphenicol - as well as co-trimoxazole – a combination known as “bactrim”, taken daily by people with HIV to prevent infections.

The study revealed soaring resistance to the two classes of antibiotics regularly stocked in Malawian hospitals, penicillins and cephalosporins, among bacteria commonly causing sepsis. In Klebsiella, the bacteria that infected Abigail, resistance rose from 12% in 2003 to more than 90% in 2016. In E.coli, resistance rose from 1% to 30% in the same time period.

“So the good news story about bloodstream infections falling is tempered by the rise of locally untreatable bacteria,” Dr Feasey said. He added: “Because in other contexts where there is a broad range of antibiotics available these infections are difficult to treat but far from impossible, but here they are effectively untreatable.”

The data is from Blantyre, and little is known about resistance patterns in other districts as no other facility has blood culture facilities, which require costly laboratory equipment and trained staff. In district hospitals it is simply known that the baby has an infection or “fever”. If they die of sepsis it is not known which bacteria caused it. If ceftriaxone, the last line antibiotic available, doesn’t work then the baby has to be referred to Queen Elizabeth hospital. “Of course you feel helpless, but I understand that we cannot afford blood cultures in every district hospital,” Dr Linda Kayange, senior medical officer at Machinga District Hospital, told us.

There are acknowledged problems at Chatinkha nursery but many babies don’t even make it there. They die at home, to families too poor to seek healthcare; in healthcare centres or district hospital without the resources to save them; or in transit en route from a district hospital to Queen Elizabeth, from the severity of their condition or because the journey can take hours. As we travelled from Blantyre to the outlying districts, mothers told us heart-breaking stories of how their babies died - of conditions and complications that could be easily treated elsewhere, but here often prove fatal (see infographic below).

Limbe market, on the outskirts of Blantyre, is a bustling place. You can barely move for the crowds of people as they walk through stalls selling colourful clothes, dried fish, chicken feet, puffed crisps and sacks of maize. At the top is a forked road locals call ‘the one that God bent’ which is home to a row of pharmacies and drug stores. We went into four to try to buy antibiotics without a prescription, which is illegal in Malawi. We had no trouble picking up a range of drugs, including injectable ceftriaxone, the ‘last line’ drug available in most Malawian hospitals. (We searched Limbe and Blantyre open-air markets for antibiotics too after hearing tales that bactrim is openly sold here, but only found painkillers for sale.)

Ibrahim Chikowe, a medicinal chemist at the University of Malawi, said that the problem with easy access to antibiotics is that people tend to take antibiotics but abandon them when they start feeling well, which leads to resistance which spreads from one person to another. “Soon you may find the population might not be cured by a particular antibiotic or class of antibiotic, and this might lead to disaster,” he said.

Cattle block the road in the rural Chikwawa district

Cattle block the road in the rural Chikwawa district

We crossed over the vast Shire river, the sun reflecting off the water, to visit the rural Khambo village in Masache, Chikwawa district. Goats grazed on the sides of the road and traffic was blocked from time to time by herds of cattle. Elizabeth Love, who lives in a straw-roofed house with a dirt floor, told us her 18-month-old daughter Rebecca had diarrhoea. She shows us two bactrim tablets she bought from a passing salesman. They expired in 2016 and are only a small part of the usual course of antibiotics that one should finish. A nearby group of village women told us salesman pass through occasionally and they would buy however many tablets they can afford.

Hospitals in crisis

Back at Queen Elizabeth hospital, Dr Kondwani Kawaza, the neonatologist at Chatinkha nursery, looked out over the ward. He told us that 20-40% of infections they are able to diagnose are now resistant to antibiotics, a figure which has risen in recent years. “Those four patients grew Klebsiella in this ward alone, in a single week. Where in the past we would say it would be for the whole month. So it’s becoming a bigger and bigger problem,” he said. He believes if they were able to properly diagnose sepsis at the hospital they would find it was the leading cause of death.

Resistance is making the care of babies with sepsis more difficult. Every day that a baby with sepsis is given the wrong antibiotic, their risk of death increases by around 50%. Even if the baby doesn’t die, sepsis can cause disabling medical complications like brain damage, meningitis and impairment to vital organs like the kidneys and the liver. Some babies may end up with life-long medical problems, whilst others may develop behavioural problems. Some of the babies infected with resistant Klebsiella have damaged guts and it is not known what the long term effects of this will be. “The biggest concern is we are treating babies and some are surviving but they are surviving with big problems that other people will have to deal with,” Dr Kawaza told the Bureau.

The hospital is lucky to be one of a handful in Malawi which has access to blood culture facilities. But by the time it takes for blood culture results to come back to confirm the infant has a superbug infection, it is often too late. “Whenever we are sure its Klebsiella, we are already 24-48 hours late,” he said. “If they don’t die today, they will die tomorrow. If they don’t die tomorrow they will die in two weeks time. If they survive, they will be weak for weeks to come. I’m already fearing that this baby in front of me will already die because we didn’t start the treatment yesterday.”

There are hospital-wide discussions about whether amikacin, and another expensive antibiotic, meropenem, can be made more widely available. But many are concerned its widespread use would drive resistance, a situation multiple medics called a disaster, as then there would be even fewer antibiotic options left.

Abigail died when she was just a month old, after contracting resistant Klebsiella. If resistance continues to rise, more babies will die, said Dr Kawaza. “Some people think that antibiotic resistance is a hypothetical threat, a non-existent threat, something that only academics talk about”, he said, adding: “But for us we do see it every day, we do see babies change suddenly from a robustly active baby to a profoundly sick baby.”

Dr Nicholas Feasey, the microbiologist researching antimicrobial resistance at the hospital, hopes his research will provide the evidence needed for changes in guidelines. More people will die from lack of access to antibiotics than from antibiotic resistance in Malawi, but it is still a problem which deserves attention and which requires solutions, he says. He connects antibiotic resistance to individual poverty, as well as to what he calls “the poverty of systems”.

But most of all he mourns the human cost of global superbugs.

“At any time you walk through the hospital though there's a high chance that a funeral procession will go by and there is just a deep sense of frustration at the waste of human life.”

Fixing and translating by Josephine Chinele. This article was published in partnership with the Times Group Malawi.

Header picture, of Lilian Matchaya and her gravely ill daughter, Abigail.

All pictures in the article by Madlen Davies, for the Bureau. Please contact us for re-use.