European doctors running low on drugs needed to treat Covid-19 patients

Hospitals across Europe could run out of the drugs needed to treat critically ill Covid-19 patients within a week, the European Commission has warned in a letter obtained exclusively by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism.

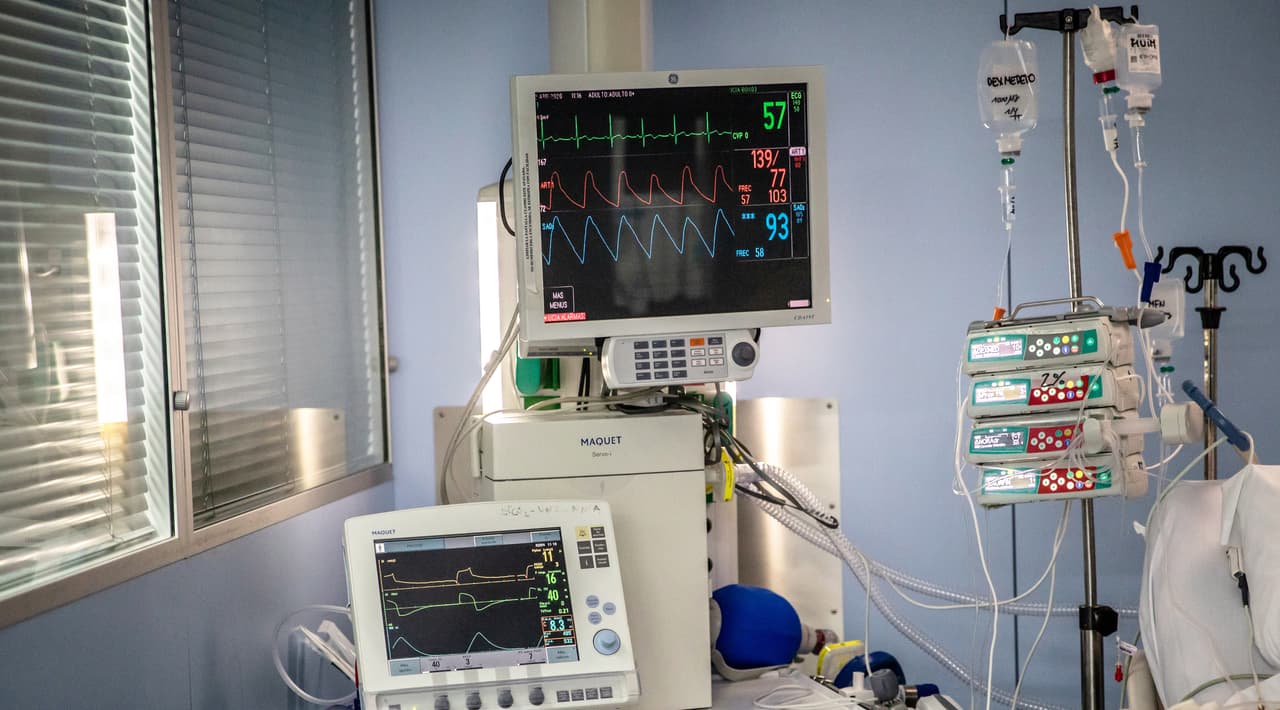

Patients who are severely ill with coronavirus require critical care. When put on a ventilator they can need up to 50 different medicines, including those for intubation and sedation, as well cardiac, respiratory and antimicrobial drugs. The most critically ill patients can stay on a ventilator in intensive care for several weeks. It presents a two-fold challenge for hospitals, with a higher number of patients needing ventilators for longer, meaning more medication is required.

The surge in demand for drugs means that stocks in many hospitals are running low, and pharmacists are increasingly unable to replenish supplies. This is forcing hospital staff to use unfamiliar drugs or alternatives, some of which could lead to heavier sedation. There are fears that this could mean more people suffer poor outcomes, including ICU delirium, a life-threatening condition where patients suffer delusions and hallucinations, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Stella Kyriakides, the EU’s commissioner for health and food safety, wrote to pharmaceutical companies at the beginning of April asking them to increase production of the medicines needed to care for patients with the virus, the Bureau can reveal in the first of a series of stories highlighting the fragility of the world’s drug supply chain.

She wrote: “The Commission will continue to closely engage with you on finding optimal solutions for the challenges at hand. We count on you to discourage unethical commercial behaviour.”

The letter, obtained by the Bureau, shows that there are already shortages of drugs including sedatives, painkillers, muscle relaxants, antibiotics, antivirals and antimalarials needed to treat patients with Covid-19 in Spain, France, Sweden, Portugal, Luxembourg, Norway, Slovakia, Ireland, Austria, Czechia and Malta.

Shortages are anticipated in Italy, Belgium, Germany, Croatia, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Liechtenstein, Finland, Greece, Cyprus and Estonia.

Last week, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, the Intensive Care Society, the Association of Anaesthetists and the Royal College of Anaesthetists released new guidance for frontline staff in the UK on how to manage the rising demand for critical-care medications during the pandemic. It includes advice on how to conserve drugs by administering them differently or switching to alternative products.

Greg Barton, chair of the UK Clinical Pharmacy Association’s critical care group, warned that the pandemic will throw anaesthetic practice “back 20 years” because low nursing numbers mean patients will require heavier sedation in intensive care. He warned that the medications used for deep sedation – midazolam and morphine — are linked with PTSD and delirium, a condition that can lead to cognitive impairment and early death.

“In normal days, we would try to have the patient as alert and awake as possible,” Barton told pharmacists in a webinar about critical care practice. Oversedating patients means that they stay in intensive care and on ventilators for longer, and are more likely to suffer pneumonia as a result, alongside other poor outcomes.

A lack of drugs has become a “limiting factor” in the care of Covid-19 patients, on top of ventilator and personal protective equipment shortages, the European University Hospital Alliance said in a letter sent to national governments at the end of March.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.

“It is extremely worrying that overworked and often less experienced nurses and doctors-in-training, drafted in to fill the gaps, have to use products and dosages that they are not used to,” the Alliance said.

Several countries have banned the export of critical-care medicines to conserve them for domestic use. The Alliance has called on countries to keep drug supply chains moving so that medicines can reach the patients that need them. A co-ordinated European response would be necessary if studies showed that drugs such as antimalarials or antivirals are effective against Covid-19, it said.

While “green lanes” – priority channels for the transport of essential goods such as medicines – have been introduced at border crossings throughout Europe, some manufacturers report that they are operating in fits and starts. Transportation issues are also still a problem for drug makers.

In her letter, Kyriakides reiterated that there is an “imminent risk of shortages of critical hospital medicines used to treat Covid-19 patients”. She asked the pharmaceutical industry to increase production of the necessary drugs with “extreme urgency”.

The list of medicines in short supply was compiled from information provided by the industry to the European Medicines Agency. The agency is working on a broader list of essential drug shortages beyond those used to treat Covid-19 patients.

Above: The letter from Stella Kyriakides to the pharmaceutical industry. If you are a journalist reporting on coronavirus and you want to see the full list of drug shortages by country, you can email the Bureau's Global Health Editor at [email protected]

Header image: A ventilator being used by a Covid-19 patient in Barcelona, Spain. Credit: Getty Images

Our reporting on coronavirus is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with us