‘A disaster waiting to happen’: how USAID’s $10bn health project unravelled

Government-funded supply chain scheme has been riddled with failings, inefficiencies, indictments and fraud allegations

Within its first two years of operation, the largest ever project funded by the US Agency for International Development (USAID) was in crisis.

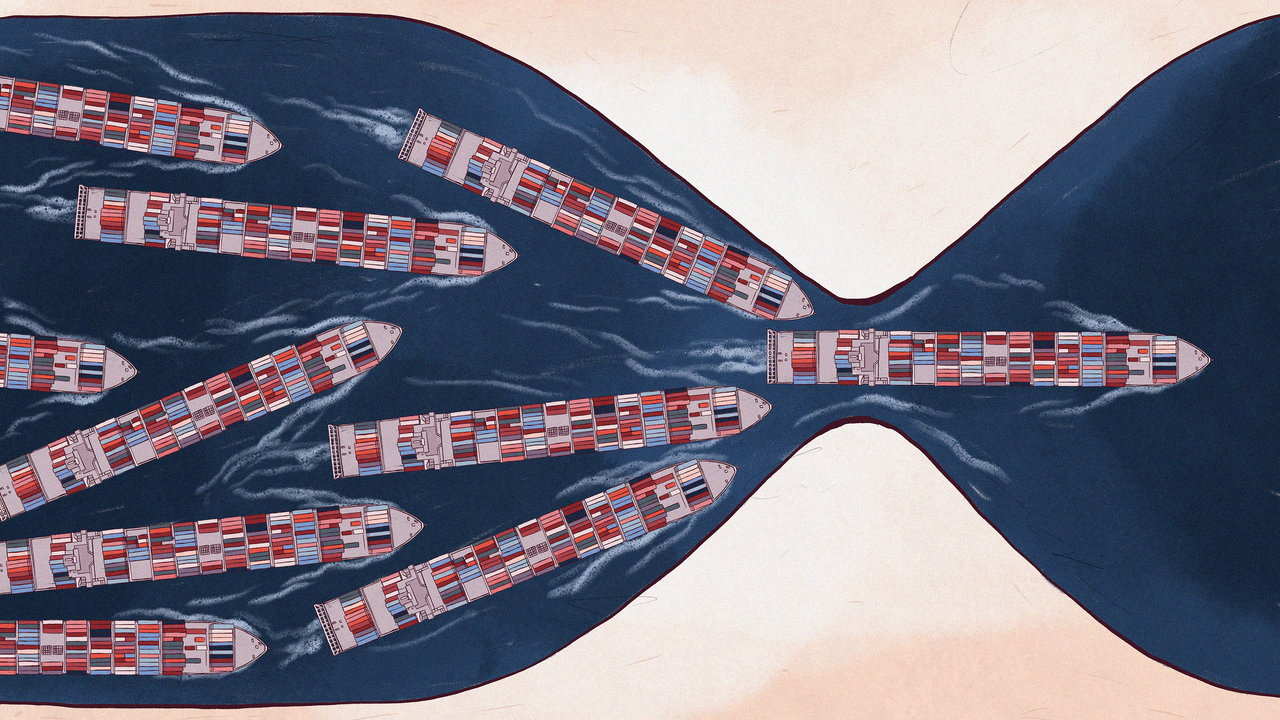

The $9.5bn initiative was led by US contractor Chemonics International. Its aim was to transform global health supply chains – the sprawling system of procurement and transport that delivers life-saving products including HIV/Aids drugs, mosquito nets and contraceptives to millions around the globe.

The supply chain served as the backbone for the US government’s most celebrated global health programmes, including the HIV/Aids initiative credited with saving 25 million lives. But this project aimed to go one step further, by improving supply chains to the point that they could be managed by the countries themselves.

If successful, said one USAID official, the agency would never have to fund another scheme like it again.

By the spring of 2017, it was clear the project was failing. During its worst quarter, only 7% of its shipments arrived at their destinations on time and in full. Project leaders scrambled as multiple countries ran short of essential health products and faced stock-outs.

Reports by Devex at the time contributed to increased scrutiny on the project, including a bipartisan investigation by the US Congress that prompted an investigation by USAID’s own watchdog. Both found significant mistakes and mismanagement by USAID and its contractor.

But over time, the project looked to be improving. Today, Chemonics says that challenges have been overcome and USAID says the project has strengthened countries’ supply chains.

Yet this public narrative of recovery is called into doubt by a new investigation by Devex and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), which raises major questions about the project’s performance. Interviews with former project staff and senior agency officials, along with analysis of the project’s data, have revealed:

New details of how serious the problems were during the early years of the project, and the level of concern among high-ranking US government officials.

Allegations by a former insider that Chemonics and USAID made the project’s performance look better by adopting easy targets and writing off bad results. In some cases, it has taken almost two years to deliver key health commodities.

Dozens of arrests and indictments in relation to illegal activity around the project, with USAID’s Office of Inspector General now investigating allegations of fraud in Nigeria.

Concerns that the project is failing to build lasting supply chains. An evaluation in Nepal found that the project was “unlikely to have any transformative or sustainable effect”.

Chemonics is a huge consulting firm that has been awarded some of the US government’s largest aid contracts and works in more than 100 countries.

A spokesperson for Chemonics told Devex and TBIJ: “We are extremely proud of our role helping to build a stronger and more resilient global health supply chain that provides access to lifesaving medication and commodities for those most in need.” They added that since Chemonics took over in 2016, the project has “procured over $5bn in drugs, diagnostics, and health commodities worldwide as of the end of March 2023, all while saving US taxpayers more than $647m on health commodities”. (USAID gave a lower value on both – “almost $4.5bn” and $586m respectively.)

But interviews with those closely involved, as well as the rare instances of external scrutiny, suggest serious problems persist. Chemonics has received multiple extensions to continue implementing the project – until at least November 2024. And after eight years and billions of dollars, there is little independent evidence that USAID, Chemonics and its partners have actually strengthened a global supply chain that millions rely on for life-saving medical supplies.

A project USAID once touted as potentially the last of its kind has failed to live up to expectations. Because of that, a new version, NextGen, will entail a “comprehensive redesign” that will include more contractors. The new project will be valued higher still, at up to $17bn. And Chemonics could be in the running to win more funding.

‘People were going to die’

Shortly after beginning as USAID’s chief of staff in May 2017, Bill Steiger began to hear alarming rumours. Colleagues warned him that vital stocks of HIV test kits and Aids drugs, supplied as part of one of the government’s flagship international health programmes, were starting to dwindle. Others said orders of mosquito nets were severely delayed, threatening to undermine malaria prevention.

The godson of George Bush Sr and an official in the administration of his son, Steiger had earned the reputation of a straight-talker. In the chaotic early months of Trump’s presidency, he was the first political appointee to begin examining USAID’s global health programmes.

Steiger said he soon discovered that the company managing USAID’s global health supply chain was losing control.

This was a disaster, Steiger thought to himself. Unlike any other USAID contract, this one was “too big to fail” – and the stakes could hardly have been higher. “People were going to die if this thing actually failed,” he told Devex and TBIJ.

The project marked a recent overhaul in USAID’s approach to delivering health supplies around the world. Multiple supply-chain projects would be consolidated into a single overarching one. And to implement it, they had nearly $10bn – the sort of money typically reserved for government defence contracts.

An agency official told potential bidders for the contract in 2013 that this new, sustainable approach could be transformative. If it was done properly, he said, the agency might never have to fund another project like this again.

In April 2015, Chemonics won the bid and instantly became USAID’s largest contractor. (In 2021, the company managed more than five times as much USAID money as its closest competitor.) But despite having worked on a range of USAID-funded projects, its most significant experience in health supply chains was limited to one project in a single country. This quickly became apparent when project staff found themselves working seven days a week to get up to speed. Orders were being tracked with spreadsheets and Post-It notes stuck to the walls of its Washington DC office.

In April 2017, USAID staff responsible for overseeing the contract sent a memo to Chemonics executives outlining seven major problems with the project, including late deliveries “in the majority of countries”, “a serious lack of communication” between the headquarters and field offices, and the project “not operating as one cohesive entity”.

Inside USAID’s headquarters, senior staff began surveying their options.

In summer 2017, Steiger gathered agency officials to discuss how USAID could compel Chemonics to improve – and was shocked to find that USAID had structured the contract in a way that left them with very little leverage.

There was no option for an offramp to take work away from Chemonics, Steiger said, nor any financial means by which USAID could penalise – or reward – the consortium according to performance. With all the health commodities bundled into one huge contract, there was also little the agency could do about particularly beleaguered parts of the supply chain.

Steiger remembers calling Chemonics’ then-CEO Susanna Mudge to tell her the project’s performance was going to be “an enormous problem for us, and an enormous problem for Chemonics if Chemonics didn’t fix it”.

Chemonics had already replaced key members of the project’s initial leadership team – though the April 2017 memo from USAID noted that restructuring efforts had “resulted in some disruption without significant improvements”.

A former Chemonics employee who spoke anonymously to avoid career repercussions described the project’s leadership as “utterly incompetent”.

In July 2017, USAID froze salary increases and promotions for the project’s headquarters staff until performance improved. Steiger then got himself appointed as the agency’s acting chief risk officer and had the supply chain contract listed as a corporate risk. It was the first time a single contract had been given that designation, he said.

The part of the contract that handled HIV supplies was a particular concern. The State Department’s then-global Aids coordinator, Deborah Birx, told Devex and TBIJ that she was forced to solve problems for a contractor that should have been performing “on day one”.

“I can’t tell you how many calls [there were] – two and three and four times a week – from countries saying that they’re close to stock-out,” she said. “Yes, we prevented them. But at what cost and what distraction?”

In a scramble to get vital treatments to patients, the project began switching from ocean shipments to air freight, which is faster but much pricier. Birx described this as “non-sustainable”.

In one instance, Chemonics allegedly sent goods to Liberia on a charter plane without securing the necessary approval from USAID. This created major tensions with the agency, according to the same former employee.

Another former employee put it simply: “I think the biggest problem was, well, Chemonics not knowing supply chain.” Chemonics did not provide comment on the project’s early struggles.

The numbers game

Many of the project’s early struggles seemed to come from the failure of the people ordering shipments to grasp the reality of what they were overseeing.

“We had procurement analysts who were just making it up,” one former employee said. “We had trash data, and then we had people who didn’t understand how humanitarian aid cargo actually worked […] It was a disaster waiting to happen.”

Chemonics leaders have repeatedly blamed the project’s previous contract-holders for not sharing crucial data with them – which the former contractors have repeatedly denied.

People who worked on the project at the time described intense pressure to provide better results as well as warnings that they should expect heavy scrutiny, including from Congress.

In April to June 2017, straight after the project’s worst quarterly performance, Chemonics reported to USAID that it had reached a “turning point”. The project’s on-time, in-full rate had increased from 7% to 23% and Chemonics executives told USAID they would exceed 60% on-time delivery in December.

“We have the client’s confidence that we can meet this target, and doing so will be an important step in earning back their trust,” James Butcher, then the executive vice president at Chemonics, wrote in a September 2017 email to staff.

Yet the improved numbers still contained major failings. HIV-related shipments, for instance, saw overall improvement during this time. But these figures were skewed by improvement related to a few items, such as male circumcision kits and lab equipment. In the same period, only three of 113 shipments of adult HIV drugs were delivered on time and in full.

The improved numbers also reflected changes in the way USAID and Chemonics were reporting on the project’s performance.

Interviews with multiple sources, as well as data analysed by Devex and TBIJ, paint a picture of a consortium so focused on how its performance appeared that it lost sight of the performance itself.

“It was clear that Chemonics was working towards specific indicators rather than outcomes and impact,” said Birx, the former Aids coordinator.

A USAID shipment arrives in Orang, Nepal

US Marines Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

A USAID shipment arrives in Orang, Nepal

US Marines Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

After realising that the project’s procurement staff were agreeing to delivery dates with little to no basis in reality, Chemonics began changing the “lead times” used to estimate how long shipments take to get into a given country.

While accurate lead times are crucial for planning, Chemonics and its partners lengthened these windows to give them a better chance of delivering shipments ahead of schedule, according to a former employee. An audit by USAID’s inspector general cited similar concerns.

In the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the lead time was kept at 180 days despite the fact that the project – even at its worst – was already capable of delivering supplies much quicker than that, the source alleged.

“We didn’t challenge ourselves,” they said. “We just kept these numbers, which we knew we could hit going forward.”

The agency’s inspector general raised concerns about lead times in a 2021 report. It quoted an email sent by USAID Mission staff in DRC which said that “the ‘agreed’ delivery date was set by Chemonics based on extremely conservative formulas – without input from the Mission, much less agreement”. It noted that there was “no choice but to approve the ‘agreed’ delivery date if they wanted to receive the deliveries”.

A USAID spokesperson said the agency regularly reviews the project’s lead times and that it believes they are “appropriately used by the project to provide realistic expectations to its customers”. Chemonics did not respond to specific questions about its data.

In effect, these extended lead times meant that deliveries that may have once been marked down as late were now considered on time. And between April 2017 and December 2018, the project’s on-time, in-full delivery rate increased from its all-time low of just 7% to the 80% benchmark.

Remarkably, though, the time it was actually taking to procure and deliver orders – known as “cycle time” – had in fact slowed over this period, from 174 days to 239.

And it has continued to slow down since. At the end of the 2022 financial year, the project’s average cycle time was 263 days, according to analysis by Devex and TBIJ. In one instance, it took nearly two years to deliver reproductive health supplies to DRC.

“Longer cycle times generally reflect a less responsive supply chain,” said the agency’s watchdog, the USAID Office of Inspector General (OIG), in the 2021 report.

Those concerns had already been borne out at a time of acute urgency. An evaluation of USAID’s response to the 2015 Zika virus outbreak found that it took two years for the project to buy and deliver insect repellants and condoms to assist in the outbreak response.

The evaluation, published in February 2019, stated that this was actually a full year faster than the project’s typical procurement cycle for these items, but still inadequate in the face of an urgent public health crisis. (USAID and Chemonics did not comment on the findings.)

Looking for a reason

The longer lead times had helped address the problem of late deliveries. But in doing so, they also created the opposite problem: too many early deliveries.

So, to deal with this, Chemonics began using early delivery “reason codes” in November 2017, with the approval of USAID. These allow the contractor (with USAID’s sign-off) to record shipments delivered ahead of schedule as “on time”, as long as it was deemed to be outside of the project’s control.

While project staff say these codes were used in previous projects and help to better identify bottlenecks, they also make the headline performance figures – the same numbers that had caught the attention of Congress and senior agency officials – appear better than they actually are.

Between November 2017 and January 2019, the new early delivery reason code was applied to 26% of items with an agreed delivery date, with nearly all recorded as being on time.

But with health supplies, an early delivery is not necessarily a successful one: it can create storage issues and increase the risk of products expiring before they are used.

The use of reason codes “does not require Chemonics to set ambitious agreed delivery dates that may better meet customer expectations”, wrote the USAID inspector in a 2021 audit.

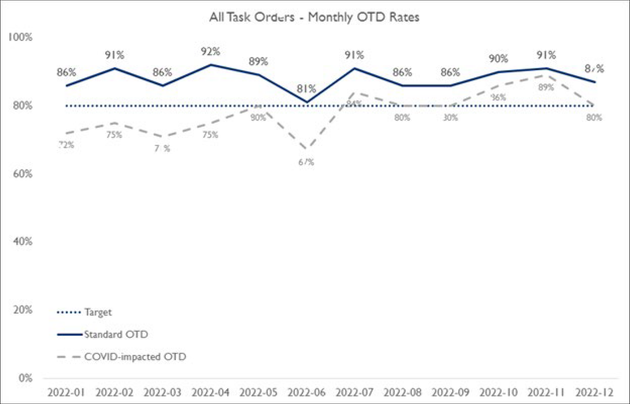

This use ramped up even further when USAID allowed the project to reclassify any deliveries it deemed to have been affected by Covid-19. In one instance, the use of Covid reason codes pushed performance levels of 42% up to 93%.

The codes were still being implemented as late as the final quarter of 2022, when deliveries of maternal and child health products were marked up from 44% to 89% because of supposed Covid delays.

Birx said she appreciated “how difficult things were for everybody” during the first year of the pandemic but could not understand why Chemonics was still using Covid to explain away late deliveries two years later.

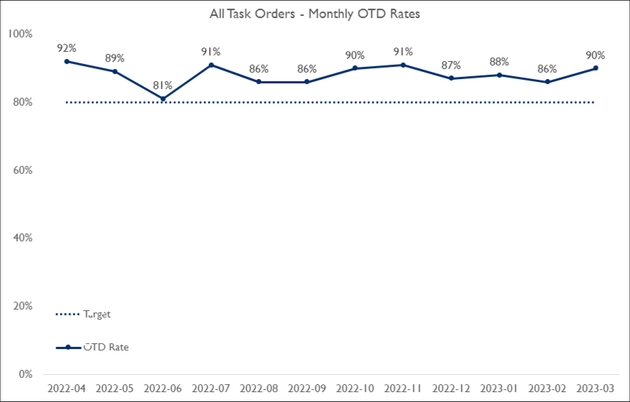

In their most recent quarterly report, Chemonics and its partners state that they have stopped using Covid-impacted performance metrics because the effects of the pandemic have subsided. And unlike in previous reports, the graph showing its performance does not include the figures before the Covid reason codes were applied, so the project appears never to have dipped below its 80% performance benchmark.

The project’s Q1/2023 report shows successful delivery rates before and after the application of Covid reason codes, which kept official delivery rates above the benchmark

The project’s Q1/2023 report shows successful delivery rates before and after the application of Covid reason codes, which kept official delivery rates above the benchmark

The equivalent graph from the report from Q2, with no Covid-impacted figures, makes it seem as though the project has never dipped below 80%

The equivalent graph from the report from Q2, with no Covid-impacted figures, makes it seem as though the project has never dipped below 80%

Chemonics did not answer questions about reason codes but a spokesperson said: “We have successfully managed the [project], including during the pandemic.” They added that the company has a “steadfast commitment to compliance and a firm belief in transparency”.

A spokesperson for USAID said the agency’s staff review, analyse and verify the project’s quarterly performance data. “The reviews of [the project]’s performance are thorough and comprehensive across technical areas, health programs, and countries,” they said. They added the agency is “confident” that reason codes are being used appropriately.

But according to the USAID inspector general, the project’s self-reported metrics have muddied the waters. Its 2021 audit reported that the changing use of lead times and reason codes meant the agency “cannot determine the extent to which its reported results reflect actual improvements in performance”.

Tech troubles

Beyond delivering health supplies, the project was also meant to help countries develop better supply chain systems themselves. A key tactic was to help them adopt more sophisticated data management systems.

One of Chemonics’ partners on this project was tech giant IBM, and USAID’s decision to award the contract to this consortium was partly because of the impressive data hub that was proposed. But the consortium had not built that system when the project began. And more than a year in, the supply chain was still running on rudimentary manual spreadsheets.

A former project employee believes Chemonics oversold what it had already developed, but this was “standard” for proposals. “You always kind of paint the best-case scenario in your proposals,” they said, adding that much of the delay was due to USAID’s over-involvement in designing the new system.

As Chemonics began to export its software to other countries and train people to use it, more issues arose.

In Nepal, logistics software was beset by bugs to such an extent that government officials did not want to use it, said a former senior Chemonics employee under the condition of anonymity. The company allegedly denied requests from the in-country team to bring in external experts to review and fix the software.

In fact, USAID mission staff in Nepal were so concerned about the project that they requested a third-party assessment, Devex and TBIJ learned.

The report, published in June 2020, found that software problems had continued: it was not “user-friendly” and there had been “insufficient buy-in” from government.

IBM told TBIJ and Devex that it was proud of the work it had done on the project and it “continuously look[s] for opportunities to enhance the global supply chain”.

Prashant Yadav from the Center for Global Development said that rather than “checking the boxes” of private sector partnership with global companies such as IBM, USAID should instead “find people who are agile and nimble, who have good tech” and adequate compliance. But he felt there is little incentive for Chemonics to do this, “because there’s no performance evaluation that is rigorous and stringent on which you can have contractual penalties”.

He said the fact that USAID still cannot reliably determine what quantity of a certain medicine is sitting in a warehouse should be a sign that “we’ve got to change dramatically”.

“After 17 years of spending money on it – not getting there? This is a serious failure.”

System failure

In addition to its tech concerns, the mid-term evaluation from Nepal put forward a damning indictment of the project as a whole. The evaluators found it was “unlikely to have any transformative or sustainable effect on the ‘supply chain’ in Nepal”.

When evaluators arrived in Nepal in 2019, the project had been running for almost three years. Yet they found that clinics and pharmacies were actually running out of some supplies – including oral and injectable contraceptives – more frequently than they had been before.

“I wanted to help my native country, where I was born and lived for 30 to 40 years […] but when I got there the first thing I found was a mess,” a former Chemonics employee said. “I wish I could say some good things about the project […] I’m very disappointed that nothing much has happened [in Nepal]. I think it was just a waste of USAID’s money.”

Asked for evidence that the project has strengthened supply chains in the countries where it operates, USAID described a “technical independence metric” that the project uses to monitor whether specific supply chain functions have moved to a local institution.

“Of the 28 countries that have reported on this metric, over two thirds have achieved technical independence in at least one supply chain function since the metric was established in 2016,” a USAID spokesperson wrote.

Given that the project works on strengthening health systems in 40 countries, this would suggest that roughly half have not achieved technical independence on a single metric.

“I think we need to ask ourselves what progress has been made at the country level now after 15 years of driving this through a parallel system,” said Birx.

When assessing Chemonics’ proposal to lead the global project, USAID looked to a previous programme the company had led in Kenya, which had also involved moving supply-chain responsibility from a contractor to a national institution. In 2019, Chemonics’ now-CEO James Butcher described the project as “a model of leaving behind a sustainable solution”.

Yet in 2021, USAID reversed its decision to channel health supplies through the national body left responsible — Kenya Medical Supplies Authority (Kemsa) — following reports it had misused millions of dollars intended for the purchase of COVID-19 supplies. The institution was in such bad shape that the US decided to void its agreement with KEMSA and return the contract for supply chain management to Chemonics. In 2022, the watchdog of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria — which funds programs alongside USAID in multiple countries — found procurement and supply chain management systems in Kenya to be “ineffective,” with “stock-outs or low stocks of health commodities at all levels.”

USAID used this project to assess Chemonics’ supply chain experience ahead of its decision to award the global contract. But when USAID’s inspector general re-examined this decision, they made a startling realisation: that the agency had incorrectly transcribed Chemonics’ performance ratings. All of the four criteria used to evaluate the company’s performance had recorded the performance as better than it actually was.

The audit said that USAID officials “could only speculate on possible reasons for the errors, saying that they had misread the spreadsheet that contained the past performance information”.

Corruption allegations

For a multibillion-dollar venture with life-or-death stakes, the supply chain project has been subject to very few publicly available independent appraisals. Most performance data is self-reported by Chemonics, and USAID has commissioned only one independent evaluation of the project as a whole.

Special agent Jonathan Schofield of the OIG warned of the dangers of this in 2017. Relying too heavily on the project’s own financial protocols, he wrote in a memo to USAID staff, “may expose the program to possible fraud and abuse”.

Schofield’s fears appear to have come true. At least 41 people have been arrested, and a further 39 indicted, in relation to illegal activity around the project since it began in 2016.

None of these people worked for USAID or Chemonics, though in another case Chemonics staff were linked to major corruption allegations. In March 2021, the Global Fund’s OIG alleged that it had uncovered a multimillion-dollar fraud committed by a Chemonics subcontractor, the Nigerian haulage company Zenith Carex. (In Nigeria, as in many countries, Chemonics works with other grant agencies, such as the Global Fund, on supply chain projects.)

Just months before being alerted to the possible fraud, a senior Chemonics employee in Nigeria had written a letter of recommendation for Zenith. It said the company had been “performing superbly” on the project, distributing supplies to warehouses and facilities. Yet at the time Zenith had allegedly been inflating invoices for its work, defrauding grant programmes of $3m.

“Chemonics’s controls were poorly implemented by negligent staff who missed key red flags when reviewing Zenith’s invoices,” the Global Fund’s report said. “Inadequate financial monitoring in the local office and US-based headquarters, combined with potential collusion between Chemonics and Zenith staff, allowed the fraud to remain undetected.”

It found that an unnamed senior project director allegedly implicated in the collusion, who signed off on all distribution invoices, was “living substantially beyond their Chemonics salary”.

In a conversation with Zenith managing director Adelana Olamilekan and his lawyer, Devex and TBIJ were told that all allegations of fraud against the company were false and that all pricing and invoices were signed off by Chemonics. Olamilekan said his company has essentially been blacklisted from working with aid groups and that Chemonics has faced no punishment.

In 2022, a year after the Global Fund’s OIG uncovered the alleged fraud scheme, it conducted an audit of the Fund’s grants in Nigeria. “Chemonics’s internal controls are inadequate,” the report states. “Information technology systems do not generate accurate and reliable supply chain data and information.” It noted that the lack of oversight poses a risk that supplies could expire or be lost or stolen.

Chemonics did not respond to specific questions about its work in Nigeria. A spokesperson for USAID said the “alleged fraud in Nigeria is the subject of an ongoing USAID Office of Inspector General investigation”. They added: “USAID is deeply committed to the responsible stewardship of taxpayer dollars and ensures fair resolution for any confirmed waste, fraud, or abuse.”

USAID supplies are loaded on to an aircraft in the Philippine Sea

Planetpix/Alamy Live News

USAID supplies are loaded on to an aircraft in the Philippine Sea

Planetpix/Alamy Live News

Next generation

Ten years after suggesting that a near-$10bn supply chain project could be so effective that USAID would not need to fund another one, the agency is preparing to announce a new set of contracts – this time valued at roughly $17bn.

In the meantime, the timeline and budget for Chemonics’ current project have only increased. Due to lengthy, unexplained delays in awarding the new funding, USAID has granted multiple extensions to continue with the project.

“They are optimising for an approach […] that is grounded in control by USAID and its US-based contractors,” said Olusoji Adeyi, who has led the World Bank’s health portfolio and also worked at the Global Fund. “I think this is a terrible case of escalation-of-commitment bias: you already committed to something, and almost regardless of the failings of that enterprise, you double down on it. That’s what they’re doing.”

The project does have its defenders. Iain Barton, a global health supply chain expert who has worked on US government-supported projects, said Africa’s pharmaceutical supply chains are “fundamentally different and absolutely improved” thanks to US support. “That’s not a narrative that’s popular with many people because it’s easier to be negative about the work that’s been done,” he said. “I think they’ve done a bloody good job.”

Before leaving USAID, Steiger, the former chief of staff, was heavily involved in designing the next version of the project, NextGen. “It was a full redesign from the beginning, from almost a blank sheet of paper,” he said.

Under the new arrangement, contracts for different parts of the supply chain will be broken up between partners. But some onlookers believe Chemonics is certain to be given a role of some sort. “The company has always acted from the beginning that this is their award and that they’re not going to lose it,” said Steiger.

In 2021, Chemonics created a subsidiary company, Connexi, to expand its supply chain business outside of global health. Several senior employees moved over to Connexi, which Chemonics has now hired as a subcontractor on the current project. One former employee said Chemonics had probably done this to build up Connexi’s past performance qualifications so it can be more competitive in future funding opportunities.

Birx, the former Aids coordinator, believes the problem is accountability. “I think sometimes that people forget who their mission is and who their client is,” she said. “Their client is not their implementing partner. Their client is the people we serve.”

Illustrations: Michelle Kondrich for TBIJ

Reporters: Ben Stockton, Michael Igoe and Misbah Khan

Additional reporting: Samuel Horti

Impact producer: Paul Eccles

Global health editor: Fiona Walker

Deputy editor: Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Jasper Jackson

This article is part of our Global Health project, which has a number of funders including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: