‘We won’t compromise’: Villagers rail against DRC’s fossil fuel auctions

Jean Bolengu Ekunja drove his spear into the ground. “We won’t compromise,” he told the crowd gathered in Baringa, a village deep in the Congo Basin rainforest. “If oil activity is what they are going to do here, they will have to kill me first, as the chief. Then they will have to slaughter all the population!”

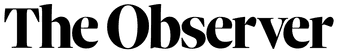

The Democratic Republic of Congo is auctioning rights to explore for oil and gas in large swathes of rainforest and other protected areas across the country. Baringa is one of scores of communities affected. The process has sparked fierce yet familiar debate about environment and development and set the stage for a legal fight over community rights, with many local people opposing extraction.

DRC’s hydrocarbons minister, Didier Budimbu, has said the country needs to extract its oil and gas “so that our children can eat and we can develop our economy”. It is the latest attempt to exploit fossil fuel resources in one of the world’s poorest countries, where almost two-thirds of the population survive on less than $2.15 a day, the international poverty line.

Many previous attempts to exploit DRC’s fossil fuel reserves have ended in failure, beset with scandal and scuppered by officials cancelling contracts.

This time around, the DRC has promised the auction will be transparent, impartial and competitive. But TBIJ revealed a process plagued with apparent preferential treatment and backroom deals.

Community opposition

Some of the oil blocks up for auction lie within the Congo Basin rainforest, which is peppered with small farming and fishing communities. DRC law requires the government to get the opinion of local people before any project or activity that may have an impact on the environment. However, the people here say they have not been asked about the auction.

Life in Baringa relies on the Maringa river

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Life in Baringa relies on the Maringa river

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

A few hours upstream from Baringa and several kilometres further into the forest is Lisoko, a farming community. With no phone network or radio coverage, the community has little access to news about the oil block auction. Nadine Bolumbu, the chief of this and six neighbouring villages, said no one apart from Greenpeace had told them about the auction. She said the villagers’ position was clear: “We owe our survival to the forest. We refuse oil exploitation in our group.” Budimbu and the Ministry of Hydrocarbons declined to comment.

The people in Lisoko gather cassava leaves and fat yellow caterpillars from the swampy forest surrounding the village, where African teak trees loom out of the water, some reaching up to 50 metres high. This tangle of trees serves as a hunting ground for wild boar, antelopes and other bushmeat, and villagers catch fish in its pools and streams. Bamboo and thick branches provide structures for their one-storey homes, many built from earth packed and cooked into bricks.

Greenpeace workers and journalists meet with villagers in Baringa to discuss the imminent threat of industrial oil exploitation

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Greenpeace workers and journalists meet with villagers in Baringa to discuss the imminent threat of industrial oil exploitation

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

The lack of infrastructure raises questions over how realistic oil exploration is. After a flight from Kinshasa, Lisoko is a two-day trip by motorboat up the River Congo and its tributaries before heading into the forest. There are few roads here, just narrow tracks for motorbikes to whip along, their drivers ducking to avoid low branches and fallen trees. Goods are transported via the river, from live goats on makeshift rafts, to barges piled high with timber.

Exporting oil from this area would involve building hundreds of miles of pipeline through dense rainforest. Similar licences acquired from the government in the past have remained unused for years due to the huge investment they require.

Vincent Rouget, a director at the consultancy Control Risks, said the current government may have intended to raise funds from the auction before the upcoming election, slated for December. Instead it has become an election issue, with the leading opposition candidate Moïse Katumbi stating that he would scrap plans to explore for oil in the Congo Basin if he wins.

The worst place in the world to drill for oil

That opposition stretches beyond the DRC. Last year, the US climate envoy John Kerry asked the government to withdraw some of the oil blocks to protect the tropical rainforest – the last in the world with enough trees to absorb more carbon than it emits. International and Congolese environmental organisations have called for the government to scrap the auction altogether.

Jean Bolengu Ekunja addresses villagers in Baringa, DRC

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Jean Bolengu Ekunja addresses villagers in Baringa, DRC

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

At least 13 of the blocks overlap with protected areas, according to Greenpeace Africa. That includes the world’s largest tropical peatlands, near Lisoko, which fan out from tributaries of the River Congo in the north-west. It has been described by experts as the worst place in the world to drill for oil, because peatlands lock-in partially decayed plant matter that, if disturbed, could release vast amounts of carbon, dramatically adding to global heating.

It is also an area rich in wildlife such as bonobos, crocodiles and forest elephants. Amid the trilling of crickets, kingfishers and hornbills, the government's promise to ensure that any oil exploration is done responsibly rings hollow. Even the highly diplomatic chief of the nearby bonobo reserve, who refused to answer questions on the auction, conceded: “You cannot do oil exploration without consequences.”

Sitting under a palm-roofed shelter out of the punishing midday sun, Albert Ifaso Bonguli, one of Lisoko’s village elders, asked: “After this exploitation, what will be left here? They’ll abandon the land with the craters, there will be water pollution, all the animals will flee.” He was unconvinced that oil would bring jobs to these communities, which desperately need funds to send their children to school and pay for medical care.

The locations of the 30 oil and gas blocks being auctioned off by the DRC

The Observer; Laura Kurtzberg

The locations of the 30 oil and gas blocks being auctioned off by the DRC

The Observer; Laura Kurtzberg

Few people here end up in secondary education, where final exams cost more than $70 – a huge sum for people whose main source of income is from the surplus bushmeat, vegetables and fish they can sell in local markets. “The villagers don't know anything about this kind of work,” Ifaso said. “The income from the oil will not benefit the Congo, only the investors who are financing the exploitation.”

The people here have already seen the arrival of the logging business, but there is little evidence that it has alleviated poverty. Joe Eisen, executive director of Rainforest Foundation UK (RFUK), said: “The promised trickle-down benefits of industries, such as commercial logging, in the form of secure employment, tax revenues, infrastructure and development rarely materialise in rural areas, with the benefits mostly captured by corrupt officials and political elites.”

RFUK has been helping communities secure legal rights to remain in the forests as their protectors. If done in the right way, Eisen said, “this currently offers the best and most equitable way to protect forests in a way that supports local development in rural areas”.

Farmers from Baringa in the forest

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Farmers from Baringa in the forest

Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Research has shown this often results in better conservation of the forest and costs less than creating dedicated protected areas. Back in Lisoko, Bolumbu says: “We protect our forests ourselves. If you want to help us, bring humanitarian aid by promoting jobs for young people, but do not touch the forest.”

Protecting Indigenous rights

Further into the forest, but still inside the boundaries of blocks parcelled up for investment, is the Balumbe community – an Indigenous people who have long been discriminated against. They have an even stronger claim against the government’s drive to sell off rights to explore for oil.

Last year, under pressure from campaigners, Felix Tshisekedi’s government introduced a new law to tackle discrimination and abuses against Indigenous people such as the Balumbe. This requires the government to obtain the free, prior and informed consent for activities that could displace them from their land – a weightier obligation than the requirement to consult the population, which echoes international standards. Thomas Fessy of Human Rights Watch said: “Now that it’s been adopted, let’s make sure that it is fully implemented and that it brings change into the lives of Indigenous communities.” He said the auction of the oil blocks could be an important test case.

The law came into force in February and no attempt has yet been made to gain the Indigenous communities’ consent for the oil auction. Observers say that could significantly disrupt the auction.

Augustin Mpoyi, a leading environmental lawyer in DRC, said if Indigenous people opposed oil exploitation, the government may choose to seize the land. “The state may feel that the revenues that oil can generate are significant and could be put to public use, and it may halt the objection. But it's going to take time. It’s going to delay oil exploitation even more.”

The government has so far struggled to attract bidders for the oil blocks and some major companies, such as TotalEnergies, have said they will not take part. Finding funding and insurance for projects to extract oil in the rainforest may also prove difficult. Many financial institutions have committed to ensuring that any projects they support have the free, prior and informed consent of affected communities. According to Greenpeace, Generali, Hannover Re, Talanx and Zurich have ruled out providing cover for oil and gas blocks in the DRC. Hannover Re said this was due to “expectations and exclusions” relating to environment, social and governance issues.

The lack of consent from the communities that TBIJ visited was evident. They may not have been consulted, but many have heard rumours of the auction. Seeing a group of outsiders speeding through the village on motorbikes and assuming they were there to take the oil, local people shouted “Thieves!”, “We refuse!” and “Get out of here!”

Back in Baringa, Ekunja said his village has not been consulted on the auctions. But they had discussed them – and their answer was clear. “Non! N-O-N!” he shouted, drawing cheers from the crowd.

Header picture: Children wash laundry in the Maringa river. Credit: Junior D Kannah/Greenpeace

Reporter: Josephine Moulds

Environment editor: Robert Soutar

Impact producer: Grace Murray

Deputy editor: Chrissie Giles

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Grace Murray

This reporting is funded by the Sunrise Project. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output. This story was produced with the support of the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network.

-

Subject:

-

Area: