‘Stifling, suffocating, unliveable’: Life in an overheating home

How the climate crisis is affecting people in the UK right now

Today, world leaders will meet in an exhibition centre in Dubai to continue discussions about the world’s climate future. Three months ago, local residents gathered at a community centre in Peckham, south-east London, to talk about how climate change is affecting them at home right now.

They were all part of the Hot Homes project, a collaboration between south London residents, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) and the University of Glasgow’s Urban Big Data Centre.

From early August to mid-September this year, 40 homes in the London Borough of Southwark – one of the hottest places in the UK – were fitted with temperature sensors.

The numbers they returned were stark. Every home in the study rose to at least 25C, the maximum safe indoor temperature for London as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). Some did so for over a fortnight. Ten homes recorded temperatures over 30C.

And much of this was during a spell that prompted headlines such as “Where has the UK summer gone?”

The figures tallied with the experiences described by the people living in these homes. One person said their home was “like a sauna you can’t walk out of”, another that it was “stifling, suffocating … unliveable”. Two people went to A&E following the heat. Others couldn’t afford to keep their fans running. Participants said they felt “scared”, “anxious” and “trapped”.

This is just a small snapshot of homes in one area. But it highlights what experts feel is a nationwide problem affecting millions of people across the UK – and one that won’t go away. At the community meeting, the message from one participant was clear: “It’s not just about planning and adapting to the future climate … It’s already a problem.”

Homeowners, private renters, council tenants and their partners, families, housemates and pets all took part in the Hot Homes project. These are their stories.

‘My body doesn’t have any chance to repair’

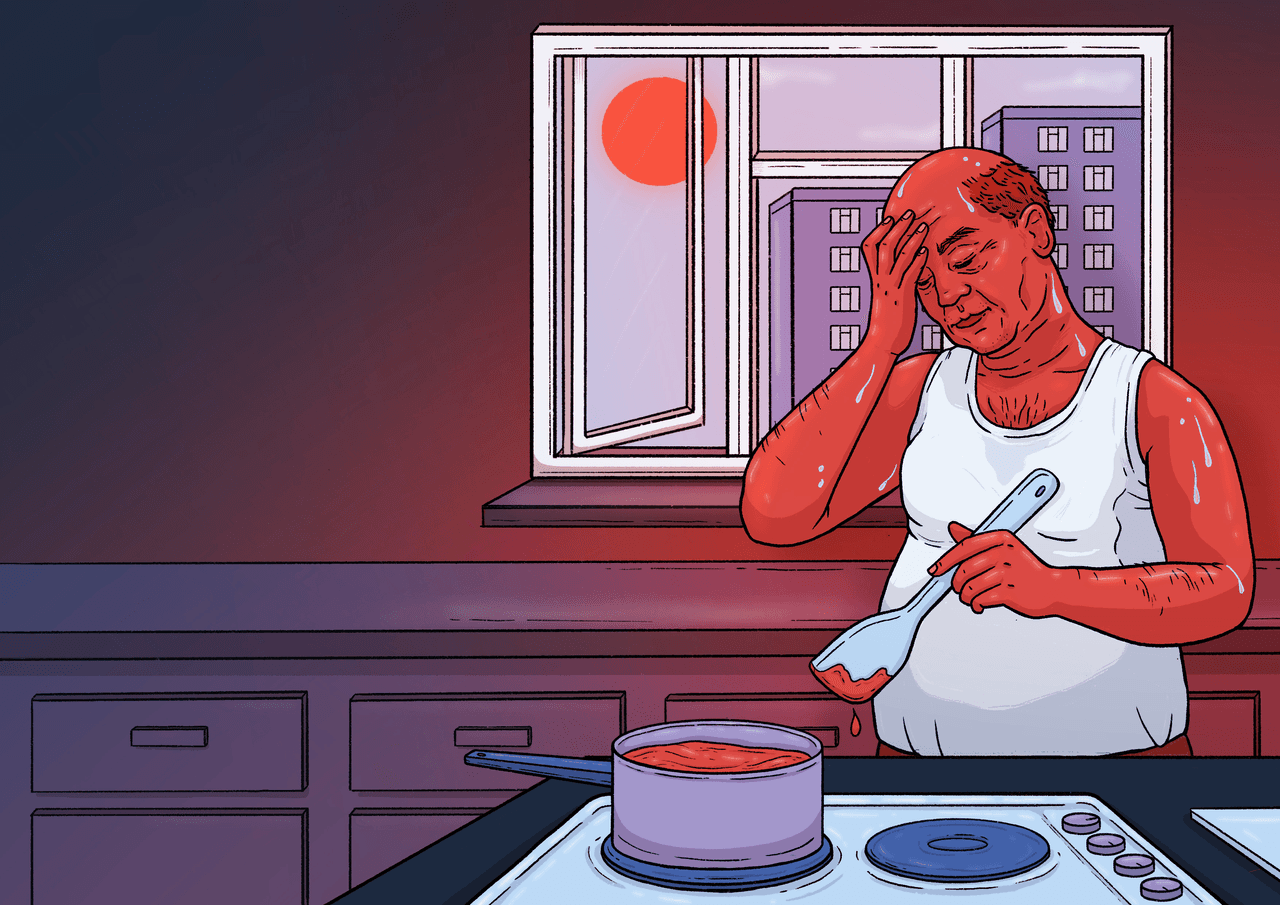

“I can be grumpy when it’s hot,” says Lee Redpath. “It’s horrendous sometimes.” Lee’s tone is self-deprecating, but he has good reason to feel prickly. The heat is bad for his health. And his home is bad for heat.

Lee, 38, lives in a seventh-floor newbuild flat he bought with his partner three years ago. “We were over the moon,” he says. Their plush, Scandi-inspired home came equipped with various features that they were told would control the temperature, including “the Rolls-Royce of windows”. But their flat hasn’t delivered on its premium promise.

In the summer, sunlight beams directly through Lee’s floor-to-ceiling windows all day long. “It’s just ‘on blast’ the whole time,” he says. He says that even with air-conditioning units running for hours, they struggle to get the temperature below 26C.

Lee says the heat in his home makes it impossible to sleep

Alex Sturrock

Lee says the heat in his home makes it impossible to sleep

Alex Sturrock

He lives on the seventh floor of a newbuild block

He lives on the seventh floor of a newbuild block

All this is especially onerous for Lee, who has a condition that affects his immune system. “And I’m going through an experimental treatment so I’m not on my usual medication. So my immune system is a bit battered to say the least.” In the heat, he says, “my body doesn’t have any chance to repair”.

In early August, Lee says, the impact of the heat on his ability to rest left him so run down that he got a chest infection. He says his chest felt like it was on fire. He was prescribed antibiotics, which Lee says usually see off a chest infection pretty swiftly. Yet this one dragged on for longer than a fortnight.

“[The heat] makes it worse,” he says. “It makes it impossible just to cool down or be comfortable enough to sleep. The heat aggravates my cough when I have a chest infection. So it’s just like a bit of a double whammy.”

Lee was one of five people from the 40 households taking part in the project who sought medical attention. Two went to A&E. Even in the cooler periods, temperatures took their toll: in the week Lee got sick, two thirds of participants said the heat at home was affecting their physical or mental health.

Urszula Kosiorek lives with her 11-year-old son in a flat she rents from a housing association. In the summer, she says, the heat triggers her son’s asthma attacks and aggravates Urszula’s fibromyalgia, a long-term condition that causes pain all over her body. She describes pain and fatigue that affect her ability to walk. “I cannot breathe,” she says.

Various health conditions can make people more vulnerable to the effects of heat, including heart issues, lung conditions and diabetes, and older people are more likely to be affected. In the warmest week of the summer, one third of respondents to our surveys said the heat at home was making an existing condition harder to manage. One participant who was recovering from a stroke saw his home reach 29C, which he said exacerbated his fatigue and memory issues.

Lee sighs as he ponders the impact his home has on his health. It’s a worry that looms the whole year round.

“I’m not getting any younger and I don’t need any excuse to speed towards the end of my life,” he says, slightly tongue-in-cheek. Then: “It just makes you feel very mortal.”

Nowhere to go

“I love my home,” says Danielle Gregory, who lives in a red-brick council-owned terrace. Inside, it’s neat and tidy, and full of colour. “It’s where I raise my family. It is my safety, my sanctuary.”

But in the summer months it transforms. “The house becomes your enemy,” says the 37-year-old project manager.

Danielle’s home rose above 25C (the WHO’s recommended maximum indoors temperature for London) on most days during the monitoring period, peaking at 29C. “It is so frightening,” she says. “You just don’t feel safe any more.”

She worries for her three daughters; her youngest has autism and finds the heat particularly hard.

Last summer Danielle decided she just had to get her children out of her home. “The heat was so extreme,” she remembers.

Urszula and her 11-year-old son in the flat she rents from a housing association

Alex Sturrock

Urszula and her 11-year-old son in the flat she rents from a housing association

Alex Sturrock

She says it’s ‘absolutely ridiculous’ that she had to evict herself from her home in the summer because of the heat

Alex Sturrock

She says it’s ‘absolutely ridiculous’ that she had to evict herself from her home in the summer because of the heat

Alex Sturrock

But working out where to go wasn’t easy. Other than public libraries, some of which Danielle says aren’t air-conditioned, the only place Southwark Council’s website recommends for sheltering from heat is the council building.

Danielle says she felt panicked as she weighed up the various factors: which places were open, whether they had aircon, how busy they would be and how they’d get there. In the end, they headed for a cinema, and she remembers the relief of the AC as they walked in. The foyer was full of homeworkers on their laptops, she says.

They did the same this summer, although Danielle thinks it’s a “crazy” measure to resort to. Nor does it come for free. People should have access to free public spaces away from the heat, she says, but there aren’t many.

Whereas some respondents to surveys said they could access public or private spaces, more than a quarter told TBIJ they had nowhere to go to keep cool when it’s hot. “It’s horrible, I want to escape but I can’t,” said one study participant.

And while Danielle can take her daughters out to air-conditioned places during the day, it’s the evenings, she says, that can be some of the hottest times.

“Just going upstairs, you immediately start sweating,” she says. “The air is thick.” She says she gets lightheaded from being up there. “It feels like there’s no escape.”

This summer, with the bedrooms too hot, Danielle and her family slept downstairs at times. “At first it was kind of fun,” she says. “‘We’re gonna camp out in the living room!’ But the novelty soon wears off.”

Her family has lived in the house for six years, but it’s only the last two that they’ve needed to sleep downstairs. She worries about what this means for the future. “It’s really down to the government to do something,” Danielle says. “Because people will die.”

“I’m a council tenant, so unfortunately I’m at the mercy of the local authority. I don’t really get to choose to move … I’m trapped.”

Lack of sleep

Until recently, Aaron George lived in what they describe as “a big concrete box built like a greenhouse” – a flatshare on the 18th floor of a tower block on the Wyndham Estate in Southwark. They’ve just moved, partly because of how hot it got during the summer. “It’s that bad,” they say.

Temperatures in the flat peaked just short of 30C this year. “It’s really, really unbearable,” they say. “Hard to put it into words really.” At night, Aaron says, the bedrooms were the warmest part of the house.

Aaron wasn’t alone in feeling the worst effects of the heat at night – some homes were as much as 8-10C degrees hotter than the outdoor temperature at night. And more than half the participants said their bedroom was the hottest room in their home.

“You’re lying in bed, you can’t get to sleep, you feel sticky, you feel absolutely disgusting,” says Aaron.

Colin Espie, professor of sleep medicine at the University of Oxford, says: “Sleep, a bit like oxygen or water or food, isn’t a ‘nice to have’, it's a ‘need to have’. It’s a fundamental requirement.

“[It] has a lot to do with the regulation of our physical, mental, and emotional functions,” he says.

For Aaron, the buildup of sleepless nights had a domino effect on their life: exercise and diet suffered. They felt unable to go out and meet friends. Their mental health took a hit. Their coping strategies crumbled.

Aaron on the Wyndham Estate, where they lived

Alex Sturrock

Aaron on the Wyndham Estate, where they lived

Alex Sturrock

They describe the tower block as ‘a big concrete box built like a greenhouse’

Alex Sturrock

They describe the tower block as ‘a big concrete box built like a greenhouse’

Alex Sturrock

At work, they couldn’t focus. “Is someone else going to notice?” they remember thinking. Their manager sat them down and voiced concern that they seemed distracted in meetings. “And then you start spiralling,” says Aaron. “‘Am I going to get fired? I’m not doing well enough.’”

The cycle continued: as stress and anxiety intensified, sleep became even harder. Aaron would find themself catching up on work at three in the morning.

Sleep disruption was an issue for nearly all respondents to our surveys, even on cooler days. Like Aaron, some connected declines in mental health with the lack of rest. Research shows that lack of sleep can affect mood, memory, stress and cognitive function, and also exacerbate mental health issues.

As one participant put it, “Everything feels out of control when you can’t even rest at home.”

Building for heat?

“Stifling, suffocating, uncomfortable and at times unliveable” is how Vikas Aggarwal described his home this summer. He lives with his partner in a flat above a busy main road with “constant traffic” outside.

The 36-year-old’s home, which he owns, was one of the hottest in our study. Temperatures peaked at nearly 31C and rose above the 25C threshold on four out of every five days.

Vikas, who suffers nosebleeds because of the heat, cites various design features that he thinks make his home too hot.

“There’s no airflow through the flat,” he says. Two thirds of our survey respondents said they couldn’t get a through breeze in their home – and an even greater proportion said ventilation issues contributed to the heat.

Vikas was also one of 80% of respondents who said that their home had no shade. “I don’t want to be outside but also it’s so hot indoors,” he says. “It feels like I’m living in a tiny hot box.”

“We have pretty large windows, which creates a greenhouse effect in our lounge,” he says. He also said that air pollution meant that he had to keep windows closed.

A 2022 report commissioned by the Climate Change Committee said that millions of homes in the UK face overheating challenges. Vikas’s home was one of the homes we looked at that was, on average, more than 8C warmer than outside temperatures at night.

Insulation, which can be effective for retaining warmth in winter, was said by more than half the respondents to be creating an issue in the summer by trapping heat inside.

“It feels like the heat is magnified into the property,” says Lianna Henry, who lives with her daughter in a flat she rents from the local authority. She adds that while she notices nighttime temperatures outside her flat drop, “inside is still furnace-like”.

Lianna says that in summer, no matter how hot it gets outside, it’s always hotter in her flat. “It’s wholly depressing, quite frankly,” she says.

Anna Mavrogianni, a professor of sustainable, healthy and equitable built environment at UCL said TBIJ’s findings corroborate trends from past research.

“Unless we prepare our homes for ongoing and future climate change, excess heat exposure will have a range of negative impacts on human comfort, productivity, wellbeing and health, with the most vulnerable in society disproportionately affected,” she said.

She described the 2022 introduction of a new building regulation in England, which set standards for overheating in new residential buildings, as “a really important starting point”.

“I believe that incorporating overheating mitigation in building regulations combined with integration of cooling strategies in any energy retrofit mechanisms is a crucial step.”

Councillor James McAsh, cabinet member for the climate emergency, clean air and streets, says Southwark’s adaptation strategy “includes plans to build resilience to overheating, by cooling buildings, providing respite from heat and preparing for extreme temperatures ...

“[But] achieving our targets requires the government to step up,” he said.

Keeping cool

Rianne Stratford’s methods of keeping cool in her flat range from the straightforward – a cold shower – to the more creative: putting chunks of ice into a metal bowl in front of the fan.

“There’s a list of things we cycle through to see which one works,” says Rianne, one of many participants for whom keeping cool was often an act of ingenuity. From ice packs between bed sheets to wearing wet clothes, various elaborate solutions were sought by the people we spoke to.

As were many simpler ones. But for some people, even opening a window to create a through breeze isn’t as straightforward as it sounds. Small children or the fear of a break-in discounted it for some; pollution, noisy traffic and smoking neighbours did for others.

For Artemis Hollamby-Ogungbesan, respite comes in the form of “a big free-standing air-cooling unit on wheels that I use when I can. I call it Harold because it’s basically part of the family at this point!”

In the hottest week of this summer, our surveys show that nearly half of our cohort said they were unsuccessful in their attempts to cool their homes. And the consequences can be far-reaching. In Rianne’s case, they’re personal as well. Her partner is autistic and overheating has triggered meltdowns. “His mental health has tanked,” she said.

Despite her ingenuity, Rianne’s best efforts to cool down wouldn’t always make a difference. “It can sometimes feel a bit hopeless,” she says.

For many of our participants, climate change is no longer a concern for the future. As one told us: “It’s something I am actually worried about right now.”

Reporters: Paul Eccles, Hajar Meddah, Rachel Hamada and Dahaba Ali Hussen

Project editor and community lead: Rachel Hamada

Bureau Local editor: Gareth Davies

Deputy editors: Chrissie Giles and Katie Mark

Editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Alex Hess

Data lead: Charles Boutaud

Fact checker: Emily Goddard

Illustrations: Nadia Akingbule for TBIJ

Photography: Alex Sturrock for TBIJ

The Hot Homes project is funded by the Google News Initiative, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Impact on Urban Health and Necessity, and is being carried out in partnership with the Urban Big Data Centre at the University of Glasgow.

-

Subject:

-

Area: