Did coerced labour build your car?

Chinese factories tied to Xinjiang forced labour feed supply chains for practically every major carmaker – and tariffs won’t stop that

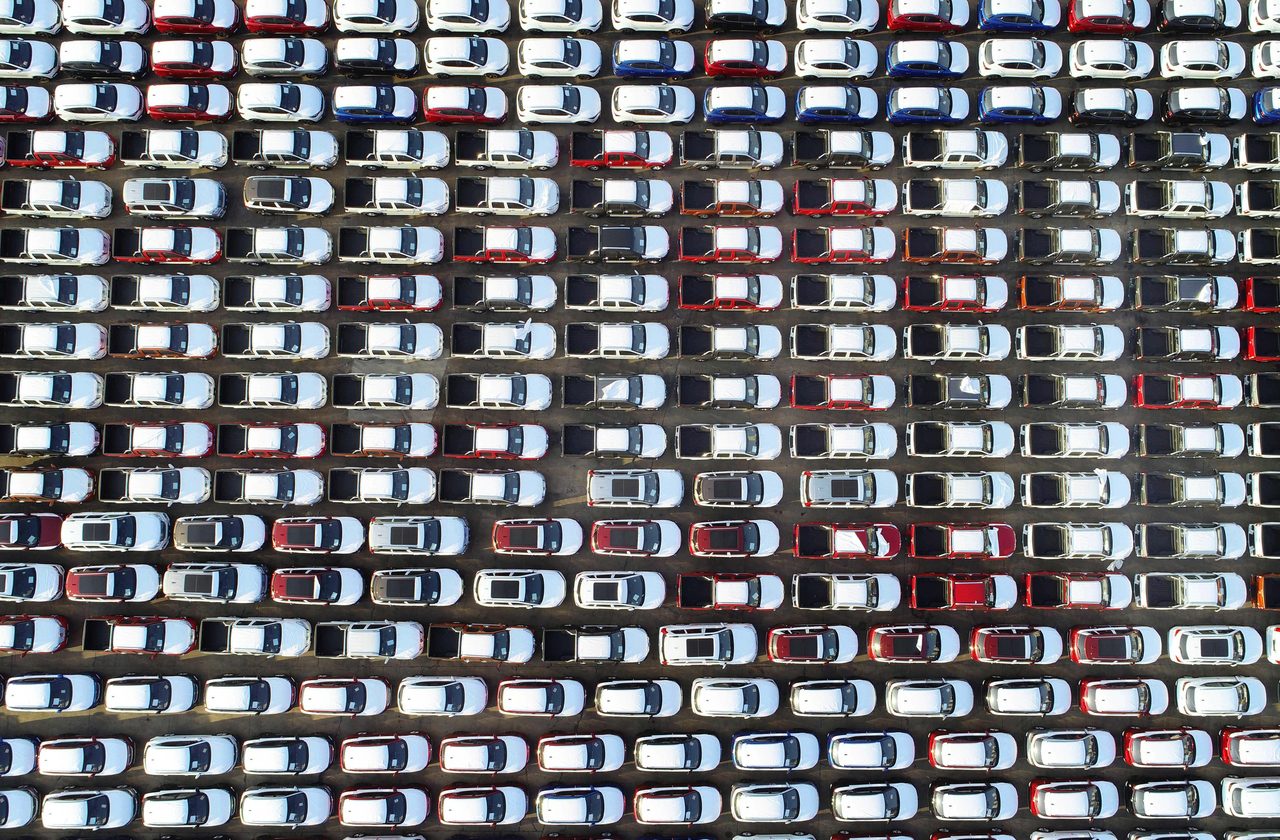

Nothing epitomises Chinese dominance over global industry more than its car sector.

Outside Wuhan – yes, that Wuhan – in Hubei, central China, a 500 km2 industrial zone christened ‘Car Valley’ can pump out a million vehicles a year.

Wuhan is a key node in China’s tech and electric car revolution and a testing ground for driverless fleets of suspended skytrains, buses and taxis. Parts manufactured in Hubei are linked to everything from one of Europe’s favourite electric vehicles to London’s black cabs. Thousands of cars ship out of factories every day.

But at the other end of the production line, workers are shipped in – thousands of Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Kyrgyz every year – from Xinjiang, the western region at the centre of a long-running human rights crisis.

Moved as part of a labour transfer scheme that experts call forced labour, these ethnic minorities are coercively recruited by the Chinese state to travel thousands of miles and fill the manufacturing jobs that recent Chinese graduates have spurned. An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has found more than 100 brands whose products have been made, in part or whole, by workers moved under this system.

At least 30 major car manufacturers are potentially implicated – including heavyweights in electric vehicles like Tesla and BYD. Even supply chains for quintessentially European brands are tainted. From touchscreens to engines, car parts made by coerced workers in Hubei, Shandong and other manufacturing hubs across China have ended up in some of the world’s most famous car brands: Mercedes, BMW, Volvo and Citroen.

Cars have been a focus of President Trump’s new tariffs

regime, which has escalated the trade war he kicked off with China

during his first administration in 2018. But across the globe, carmakers

have come to depend on Chinese manufacturing chains, many riddled with

forced labour. Tariffs may add to the costs of cars, but seem unlikely

to protect China’s most vulnerable workers.

Next day delivery

Trump’s tariffs on cars and car parts have inadvertently laid bare how international the modern car assembly line is, with individual parts crossing borders half a dozen times before a car is finally built. Hyundais, for example, are ostensibly South Korean. However, like most of the South Korean car industry, Hyundai’s assembly plants depend on Chinese supplier factories, mostly in Shandong.

The factories produce wiring harnesses, huge bundles of wires that connect everything in a car together, from headlights to the engine. As cars become increasingly smart, electric and interconnected, wiring harnesses are getting heavier, larger and more complex. Fully extended, a single harness would stretch over several kilometers.

Threading this mass of wires into a cohesive system ready to implant into a car chassis is fiddly, time-consuming and labour intensive. Videos from factory floors show Uyghurs standing at assembly boards, routing, bundling and securing cables, like fiendishly complex hand-weaving.

Relying on just-in-time shipping to South Korea, the factories are such a critical bottleneck that, when Covid-19 shut down Shandong’s wiring harness workshops, Hyundai’s Korean car plants fell silent too.

“We are the most critical wiring harness supplier for Hyundai and Kia in South Korea,” a director at one of the companies using Uyghur workers told Chinese media during the pandemic. “If Korean customers do not receive our products on the same day, the entire automobile industry production line will be disconnected and stopped.”

Hyundai, which owns Kia, said it had “found no record of employment of ethnic minorities” from Xinjiang at the supplier companies TBIJ identified. It said it requires suppliers to meet “strict human rights requirements” that it regularly monitors.

But South Korea is far from the only manufacturing hub dependent on Chinese factories for parts.

Since the start of Trump’s trade war, both Chinese overseas investment in rival global manufacturing hubs and exports to them have ballooned. China’s shipments to Vietnam rose by 18% to record levels in 2024, seeing the country overtake Japan as China’s third largest export destination. Exports to Mexico more than doubled in the six years to 2023, when the country surpassed China as the biggest exporter of goods to the US.

China’s largest LED chipmaker, Sanan Optoelectronics, has two factories in Fujian and Hubei that take Xinjiang workers transferred by the government. The company makes car lighting for premium brands like Rolls Royce, according to its website. A new partnership in Chongqing manufactures chips for Tesla.

But trade records show Sanan also ships optical chips to Samsung in Vietnam for use in high-end display panels. The company has a long partnership with Samsung to produce parts for its tablet, laptop and car displays. Samsung said it conducted “rigorous due diligence” and supply chain audits, and that a recent inspection had “found no evidence of forced labour related to Samsung products” at the supplier companies TBIJ identified.

TBIJ found parts for cars, electronics, home appliances and footwear flowing across borders to production hubs in countries like Egypt and Indonesia, which then ship goods to the EU and the US. In some cases, the overseas factories are owned by the same Chinese interests – an arrangement that Marco Rubio, the US Secretary of State, has described as a “country-hopping” loophole to avoid US tariffs.

China’s drive to the top

Since the start of the 2010s, China has funnelled more than $200bn into carmakers, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Spending rose dramatically in 2018 and has stayed high.

Car Valley has been a vital centre for the rise of China’s automotive industry, especially for electric vehicles. Despite its location deep within central China, Car Valley’s international exports have grown steadily in the past five years — reaching more than 100,000 vehicles last year, according to state media.

Cars travel east via river to China’s bustling seaports, and westwards overland by the China-Europe railway. Trade by rail has been buoyed by the Red Sea shipping crisis. A car can roll off the production line in Hubei and arrive at the border of Europe in about two weeks, faster and cheaper than most sea and air freight.

A China-Europe freight train loaded with finished cars for export

Tang Yi/Xinhua/Alamy

A China-Europe freight train loaded with finished cars for export

Tang Yi/Xinhua/Alamy

Car Valley hosts scores of projects with global companies and welcomed some of China’s earliest joint ventures with foreign car brands in the 1990s. Foreign companies looking to do business in China often need to do so through partnerships — joint ventures — with local companies. One of the Wuhan car factories tied to the Xinjiang labour transfer scheme is a Sino-Finnish interest.

It’s an arrangement, research shows, that helps the government exercise control over foreign investments.

But Car Valley also “welcomed” at least 1,500 Xinjiang transfer workers in 2022, according to state media reports. The following year, the provincial government said it “helped” more than 4,000 people from Xinjiang into work at 65 Hubei companies.

More followed in 2024. In February that year, Abdulrahman* posted a clip to Douyin, Chinese TikTok, showing himself among a group of ethnic minority workers travelling by train through Xinjiang. All of them were wearing red hats bearing the logo of Xinjiang Zhengcheng Minli Modern Enterprise Services, a labour dispatcher owned by the Xinjiang government.

Twelve days later, Abdulrahman uploaded a selfie showing himself in the smart white and red overalls of Great Wall Motors, a leading Chinese carmaker. At least a dozen other Xinjiang ethnic minorities posted from Great Wall Motors in 2024.

Labour dispatchers like Zhengcheng Minli get cash rewards for each worker sent out – as do the party officials going door-to-door to pressure villagers into transfers. At the other end, the factories are also rewarded if they take more than 30 ethnic minority workers for a year or more. TBIJ found an annual report detailing thousands of dollars in “Xinjiang employment assistance” subsidies for one company.

Zhengcheng Minli’s TikTok feed confirms it has sent workers to more than a dozen factories in Car Valley and further afield.

One of them is Jinrui Technology. The factory specialises in engine parts and is a key supplier for Geely, a Chinese carmaker that serves as a good example of how broad China’s command of the auto industry has spread. After a series of deals, Geely now owns Lotus and Volvo, as well as the electric vehicle (EV) brands Smart, Polestar and Lynk & Co. Once run from Norfolk, Lotus cars sold in the UK are now built at a plant in Car Valley. Geely also owns the British company that builds all of London’s EV black cabs.

A Geely-owned car factory in Shanghai

Lou Linwei/Alamy Stock Photo

A Geely-owned car factory in Shanghai

Lou Linwei/Alamy Stock Photo

Engine parts made at Jinrui have been shipped to a Geely factory in Skövde, Sweden, that helps build Volvos, Nissans and Renaults. Chinese state media says the factory has also supplied BMW, General Motors, and the EVs of Jaguar Land Rover and BYD.

TBIJ found videos from Uyghur workers at Jinrui posted in 2024. Zhengcheng Minli’s own feed includes one of their recruiters interviewing Uyghurs deployed to Jinrui. “It’s not long since I started work, I haven’t gotten a salary yet,” one man says. “It should be no less than 6,000 yuan.”

Geely said it prohibits the use of forced labour by its suppliers.

An electric revolution

The most prominent player in Car Valley is Dongfeng Motors. Founded in the late 1960s by order of Chairman Mao, the state-owned carmaker now builds Europe’s cheapest EV model — Renault’s Dacia Spring — in Hubei. It also produces its luxury EV brand Voyah, available in Europe, in the valley.

Dongfeng, which sold its 60 millionth car last year, is at the centre of Beijing’s plan to turn Car Valley into a hub for electric vehicles. The “Made in China 2025” plan, issued a decade ago, called for a massive expansion of industrial capacity, particularly in three strategic, high-value export sectors: EVs, lithium batteries and solar panels.

Late last year, a local consortium led by Dongfeng celebrated the development of China’s first high-end automotive microchip – helping close a technology gap worsened by restrictions imposed by the US and its allies on Chinese access to advanced semiconductors.

TBIJ’s investigation found evidence of Xinjiang labour transfers to at least six of Dongfeng’s supplier factories in Hubei. Some Dongfeng EVs are shipped all the way from Hubei to Sweden on the China-Europe railway.

However, China’s EV juggernaut is BYD. Relatively unheard of overseas until recently, the brand has wrested dominance of the global EV market from Tesla and is on a major expansion drive. The maiden voyage of its 7,000-car carrier in January 2024 took thousands of vehicles from China to the Netherlands and Germany. BYD has been endorsed by Leonardo DiCaprio and the footballer Ollie Watkins and nabbed slots on primetime British television to promote its brand.

Evidence gathered during the investigation indicates that at least nine factories tied to BYD – in Hubei, Guangdong, Jiangsu and Tianjin – are also participating in the Xinjiang labour transfer programme.

“If I say that I’m exhausted I’m breaking taboo, if I say I'm not exhausted, I'm lying,” intones a Uyghur proverb slapped over a video posted December 2023. Yakub*, the man who posted it, films himself walking in a factory compound in the Wuhan zone, mumbling along to the words. His cap bears the logo of Xincheng Auto Parts, a Jiangsu parts maker that set up shop in Wuhan and has supplied BYD, Tesla, Toyota, Chery and Kia as well as joint ventures owned by GM, Volkswagen, Honda and Nissan.

Since late 2022, when the company started recruiting on Xinjiang government social media, several Uyghurs working at Xincheng have posted videos online. “I cry for the withering of the rose, I cry for the filling-up of the heart” goes a song attached to a video posted by Yakub as he walks through the workshop.

BYD has long supplied parts for London’s red buses

Terry Blackman/Alamy Stock Photo

BYD has long supplied parts for London’s red buses

Terry Blackman/Alamy Stock Photo

While its cars are only just rolling onto roads in the UK, Londoners are already intimately familiar with BYD’s vehicles — the company has long supplied the engine systems and chassis for the city’s iconic red buses. Stagecoach, First Bus and National Express are also customers.

Chinese state media suggests Xinjiang workers were sent directly to BYD’s electric bus factory in Guangzhou, Guangdong province.

Transport for London said none of the factories highlighted by TBIJ were on a list of suppliers that BYD had “voluntarily shared” with it. First Bus said that its standards prohibit “forced, compulsory or trafficked labour” and that it was in touch with BYD to investigate. Stagecoach said it had similar policies and standards and emphasised it required all suppliers, including BYD, to follow them. National Express declined to comment.

International dominance

The breakneck ascent of China’s car brands internationally has only become truly apparent in the last few years.

Amid a collapsing property market, Chinese consumers have pared back spending, prompting fears of stagflation. The government responded with stimulus packages that incentivised trading in old vehicles for new EVs. “Consumption is an important engine of economic growth," said Liu Ziqing, top official in the Wuhan zone in 2023.

But expanding international exports remains China’s go-to strategy.

In late 2019, the state-owned SAIC Motor was the first to ship electric cars — the re-launched, formerly British MG marque — to Western Europe. The first Polestars, a Geely/Volvo collaboration, arrived the year after. Car exports almost quintupled in the following years to 2023, according to data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers. That same year, China claimed the mantle of the world’s top car exporter, and it now builds about double the number of vehicles it sells domestically, according to The Wall Street Journal.

And it’s not just Chinese brands now selling Chinese cars. With overproduction, rising competition and a vicious price war in the Chinese market, foreign car brands with factories in the region have switched from serving local consumers to shipping worldwide. Tesla started shipping cars to the EU from China in 2020.

Western car brands are ailing within China; Chinese consumers want Chinese cars. Now, BMW, Volkswagen, Honda, Ford, Renault and Volvo all build in China and export to Europe. Foreign auto brands accounted for a third of the cars exported from the country to Europe last year, according to the industry analyst Matthias Schmidt. But their Chinese rivals are also penetrating deeper and deeper into European and North American markets.

The UK is the largest European market for Chinese cars, say analysts. One in ten cars imported is now from China. Mike Hawes, chief executive of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, has said that the Chinese market share for EVs is even higher: accounting for China-built cars, like Teslas, roughly one third of all EVs on UK roads are Chinese.

The UK government has signalled that it won’t levy tariffs on China’s EVs — as the US and EU are doing – a decision that was warmly welcomed by BYD. That means Britain has become “a safe haven market for Chinese manufacturers”, said Schmidt. The government’s energy strategy includes significant commitments on pushing EVs, which it sees as “a crucial step towards achieving the UK’s net zero target”. In early 2025, BYD urged EU lawmakers to “copy the UK”.

Last month, the chancellor Rachel Reeves said she would be happy to ride in a Chinese-made EV. But concerns over forced labour were highlighted later that month when the government said that legislation creating a new state-owned energy company would specify a slavery-free supply chain for its solar panels, largely due to concerns over Xinjiang.

“The UK is increasingly a major dumping ground for products made with forced labor,” said Chloe Cranston at Anti-Slavery International, the world's oldest international human rights organisation. Seen a decade ago as at the forefront of legislation to tackle modern slavery, the UK’s approach is now widely seen as obsolete.

“We need new laws which hold companies accountable for failing to take meaningful steps, and which ban the import of products made with forced labour,” Cranston added.

Tesla, Toyota, Renault, Honda, BYD, SAIC, Dongfeng Motors, Great Wall Motors, Chery, Sanan Optoelectronics and Xincheng Auto Parts did not respond to several requests for comment.

Volkswagen, BMW (which owns Rolls Royce), Nissan, General Motors, Ford, Jaguar-Land Rover and Mercedes-Benz said that they regularly inspect for human rights issues in their supply chains and take steps to investigate whenever concerns are brought to their attention. BMW and Mercedes-Benz noted that they were investigating at least one supplier in response to TBIJ’s investigation. Volkswagen said it was investigating the allegations but could not comment further.

Reporter: Daniel Murphy

Desk editor: Frankie Goodway

Editor: Franz Wild

Fact checker: Ero Partsakoulaki

Production editor: Frankie Goodway

Illustrations: Marta Kochanek. Some images courtesy of Xinjiang Police Files.

This investigation was supported by the Pulitzer Center and the Fund for Investigative Journalism. TBIJ has a number of funders, a full list of which can be found here. None of our funders have any influence over editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject: