Was Gaddafi ‘cyber spying’ on opponents in the UK?

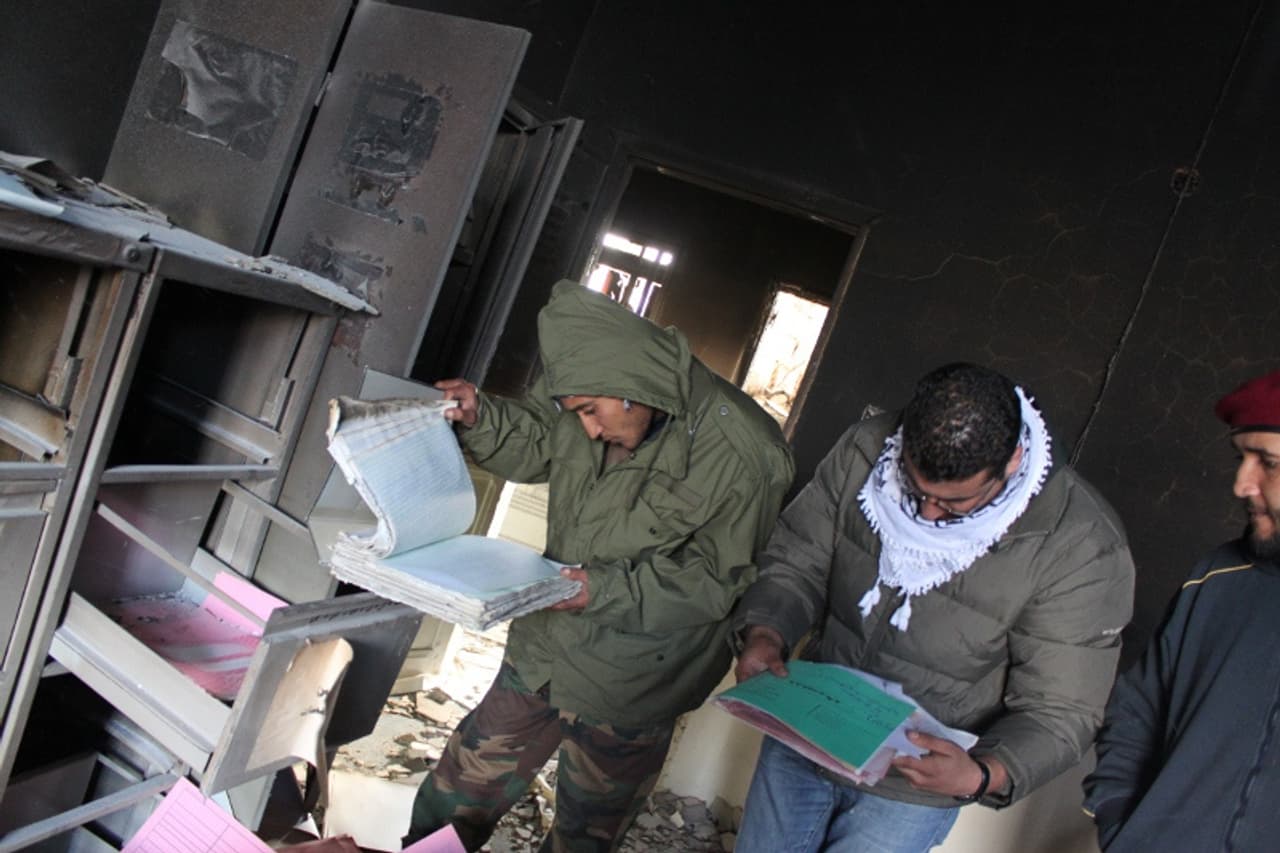

Libyans examine files in the security headquarters, Tripoli, February 20. Image: Al Jazeera

The operating manual for a spying system built for Colonel Gaddafi may have contained the email addresses of a British lawyer and the new Libyan ambassador to the UK, suggesting that the oppressive regime’s ability to electronically spy on opponents may have extended to Britain.

Amesys, a French company, sold its ‘Eagle’ online surveillance system to the Libyan government in 2007.

The technology is marketed for monitoring terrorists and serious criminals, but it appears the Gaddafi regime may have used it to keep tabs on political opponents, including those overseas. There is no evidence that anyone was harmed as a result of the Amesys system. But a Libya-based individual who is identified in a draft of the manual was summoned in 2009 to explain his emails by Gaddafi’s feared spying chief, Moussa Koussa. It is not known, however, whether this was directly connected or not.

The Libyan surveillance centres were discovered in August by the Wall Street Journal, but this is the first time it has been suggested the technology may have been used outside Libya.

“I have never had anything to do with Libyan internal or foreign affairs… it’s always going to be a surprise to find out you’re on the receiving end of a foreign government’s spying.

Jeffrey Smele, Simons Muirhead & Burton

Following the Bureau’s revelations that Gaddafi may have spied on individuals in London, Daniel Kawczynski MP, Conservative leader of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Libya, has said he intends to write to the prime minister on the matter. Mr Kawczynski will urge David Cameron to ask President Sarkozy why a French company sold such technologies to a repressive regime.

The draft Eagle operating manual, obtained by French website Owni and seen by the Bureau, is dated March 2009 and contains screengrabs appearing to show the system in action. Emails and other identifiers have been redacted, but these redactions were easily reversed.

When contacted by the Bureau, Amesys said: ‘The Libyan authorities were the only ones in a position to operate the equipment. Amesys therefore, has never compiled any list for the Libyan authorities. The manual you are referring to, contains screengrab[s] exclusively provided by the customer, including page 52. Amesys does not operate any listening centre anywhere in the world.’

Targets for surveillance

One screengrab features the email addresses of many individuals based in Britain.

The 40 addresses and phone numbers in the image, some of which are aliases for the same person, include those of members of Libya Forum, a network of dissidents based in London, Washington and Helsinki. It appears that this is only half of the list.

The name at the top, ‘Annakoa’, has been identified as Mahmud Nacua, the new Libyan government’s ambassador to London. When the draft manual was compiled, he was a prominent dissident, living in London and writing for several Arabic newspapers and magazines.

Mr Nacua told the Bureau he first learned that he may have been under surveillance earlier this year. ‘I’m not surprised – in the past I had a website, and Gaddafi’s intelligence hacked it and destroyed it. This was five or six years ago. The main purpose for [monitoring emails] was to know what I was up to, what I was writing.’

Mr Nacua told the Bureau he first learned that he may have been under surveillance earlier this year. ‘I’m not surprised – in the past I had a website, and Gaddafi’s intelligence hacked it and destroyed it. This was five or six years ago. The main purpose for [monitoring emails] was to know what I was up to, what I was writing.’

He added: ‘When you use this revolution of technology to serve people, to improve their lives, to protect them from criminals, that’s good. But when it goes to the other side, to be used in a bad way, I think everyone would condemn that use of technology.’

In an indication of how far Gaddafi’s overseas surveillance network may have spread, the list also names a London-based lawyer, Jeffrey Smele of media lawyers Simons Muirhead & Burton. Smele’s only obvious connection to Libya is that he once helped defend a defamation case against Ashur Shamis, editor of the Akhbar Libya website, who is also on the list.

It is not clear whether the apparent list of targets was assembled using Eagle, or whether human intelligence or other surveillance were used. However, Smele’s inclusion, given his tangential connections with Libya, suggests that at least some of the addresses may have been harvested from the email accounts of other targets.

Smele told the Bureau: ‘I expect that sort of thing from the Gaddafi regime, but I was surprised that someone with only my peripheral involvement in one libel case regarding a UK-based Libyan blogger could end up on what appears to be a weapon system – because if it’s a surveillance system, that’s effectively what it is.

‘I have never had anything to do with Libyan internal or foreign affairs…it’s always going to be a surprise to find out you’re potentially on the receiving end of a foreign government’s spying,’ he added.

The Bureau contacted five other individuals on the list.

Dr Younis Fannush, a Libyan writer, lived in exile for 20 years, returning to Benghazi in 1997. He wrote for Ashur Shamis’s website Akhbar Libya under several pseudonyms, and was in contact with other members of the Libya Forum.

Dr Younis Fannush, a Libyan writer, lived in exile for 20 years, returning to Benghazi in 1997. He wrote for Ashur Shamis’s website Akhbar Libya under several pseudonyms, and was in contact with other members of the Libya Forum.

The objective of this development programme is to be able to trigger phones of selected persons and be able to listen to their discussions using their GSM phone as a microphone and without their awareness.

Amesys proposal to Gaddafi regime.

In 2009, he was summoned to Tripoli, to the office of Moussa Koussa, then Gaddafi’s chief of external intelligence.

‘I went to that meeting thinking I would never come back: I was expecting to go from his office to jail, or worse, because I knew I had been acting against [Koussa] and Gaddafi,’ Fannush said.

At the meeting, Koussa produced print-outs of Fannush’s email conversations with Ashur Shamis and other members of the Libya Forum.

‘He knew everything about my connections with my colleagues in London, and all the names I was writing under,’ he said.

‘He didn’t show me the police face of the regime: he was very kind and very gentle with me. He told me, what you’re saying is natural; Libya is your country. You have a right to write things, and if you need anything, I’m ready. I thanked him and said I got the message,’ Fannush continued.

Fannush interpreted the meeting as a warning: ‘It was a message that they knew everything, and a message to stop [writing for dissident outlets]. So I did.’

There is no clear evidence linking Amesys’ technology to Koussa accessing Fannush’s emails. However, Fannush’s email address is in the draft manual created in March 2009.

Amesys signed contracts for the equipment in 2007, and installed it in 2008.

Image from Amesys’ technical specification showing the monitoring centre

Inside the Eagle deal Documents seen by the Bureau reveal the potential extent of collaboration between the French company – which at that point was called i2e – and the Libyan government. An unsigned draft of the contract and a detailed technical specification, both dated 2006, outline the systems Amesys proposed to create for Gaddafi’s regime as part of the Homeland Security Program. Amesys proposed a wide-ranging system, including security and encryption protocols for the country’s phone, email and computer networks. The proposal entailed ‘communication and data interception’ of mobile and fixed lines, email, and computer exchanges. These would allow the authorities to locate and even to remotely activate microphones on mobile phones. ‘The objective of this development programme is to be able to trigger phones of selected persons and be able to listen to their discussions using their GSM phone as a microphone and without their awareness,’ the proposal states. Amesys proposed to send two engineers to Tripoli to train Libyan engineers in how to use it, with a further three engineers working in either France or Libya to custom-design the phone eavesdropping system. The contract seen by the Bureau was only a draft. When contacted by the Bureau, Amesys said the contract it signed related to analysis hardware for a few thousand internet lines, and did not enable the regime to access satellite internet communications, encrypted data such as Skype, web filtering, or fixed or mobile phone lines. It also pointed to a previous public statement on the website of its parent company, Bull.

Simons Muirhead & Burton provides legal advice to the Bureau.