Court in the net

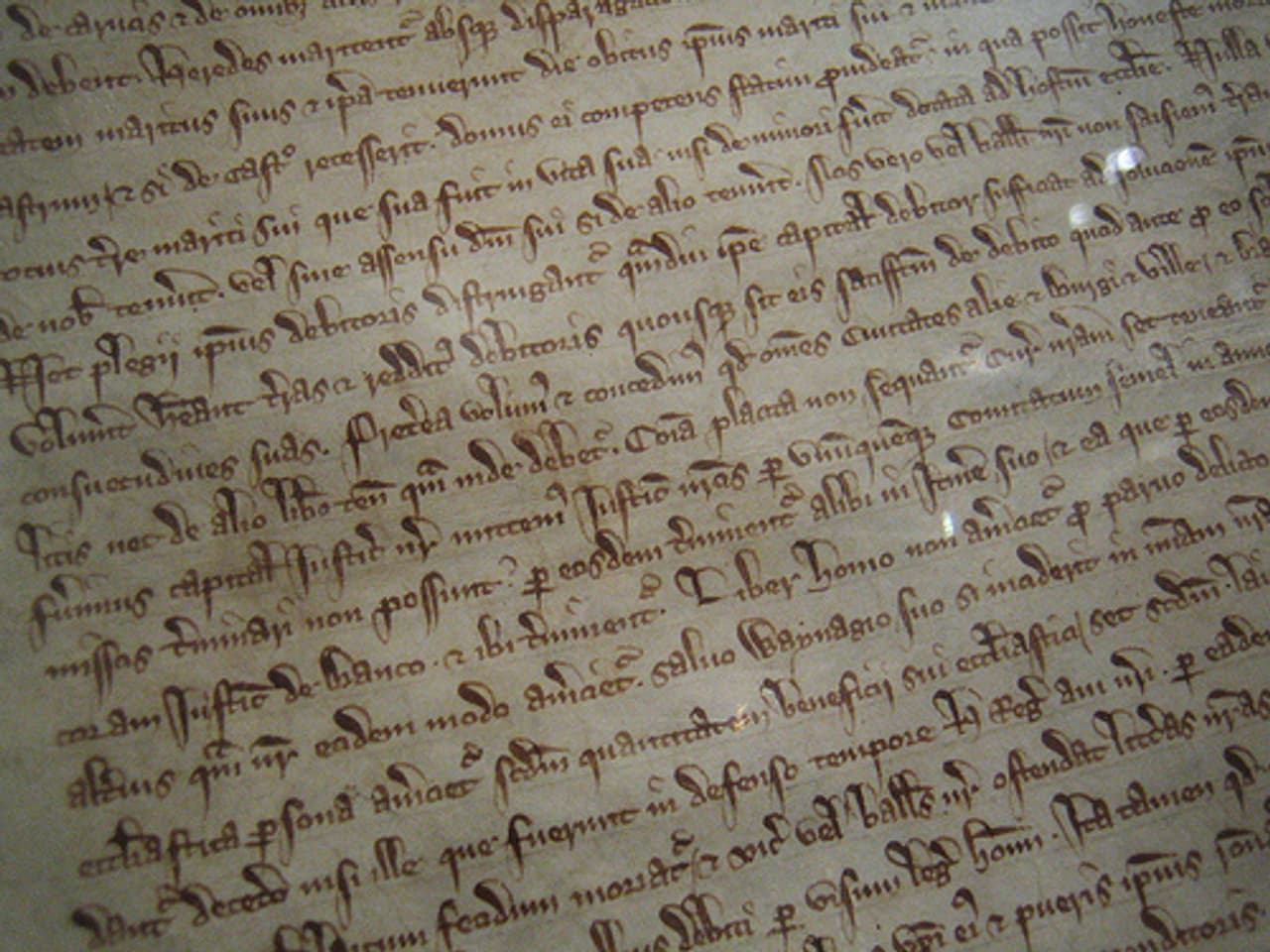

A modern Magna Carta for a more transparent court system (Image: Flickr)

Across the UK are hundreds of simple local websites that report community news and events. Crime and anti-social behaviour are the most challenging topics they have to tackle. In London’s Kings Cross, where I run a website, the crime issues have been acute from anti-social behaviour to murder and large-scale organised crime. Most local sites do not want to add to local fear of crime by just reporting incidents; we want to publish results and support our local criminal justice professionals in the police, crown prosecution service, courts and prisons. Finding out what is going on in local courts would be very useful.

I want to keep my community informed about what happens at our local magistrates’ court where justice is dispensed on our behalf. But as a local website I cannot secure a simple list of upcoming events nor a list of results to publish for all to see. I would like daily court results and timetables posted to a courts website, preferably with an RSS feed. After all, you can go to the court and watch from the gallery or see the screens. I have tried getting basic information from my local magistrates’ court but have been defeated. I sought basic material, such as a list of cases and results (i.e. which local people are up in court and who is innocent and guilty) – the type of information that gives people confidence that the system is working.

Journalists complained to me that even though they have a privileged position, their job was not much easier and getting worse. They said that court officers seemed confused or ignorant the complex and overlapping protocols of ‘data protection’ and ‘copyright’. As the resources and reach of the local press declines, the courts and the government should make it easier to get basic justice information to the public, not harder.

We ought to expect better of a modern transparent system, costing hundreds of million pounds.

In 1911, a paper based system where you queued up in person for a chitty with little certainty of success may have been fine; in 2012 it’s wrong; I can’t understand why basic information about our courts isn’t available online. The courts are awash with procedural paper, presumably generated electronically at some point. It’s very simple to publish to the web these days: all you need is access to email to send a Word document or spreadsheet to the publishing services Scribd or Posterous. Nonetheless, we ought to expect better of a modern transparent system, costing hundreds of million pounds.

The government appointed me to its Crime and Justice Sector Transparency Panel. With the government’s drive to transparency and open data I tried to get to the bottom of the problem of obtaining electronically routine information about local courts. I brokered a meeting between a specialist court reporting and news agency, Central News, and Ministry of Justice (MOJ) officials. The court reporters set out a fairly dysfunctional experience as they sought to get basic, consistent, common sense information from Court officials. MOJ staff were very helpful and undertook to address problems but it struck me that, given the other pressures following the riots in summer 2011, MOJ has an insurmountable managerial task to re-educate court staff in the minutiae of information management.

To my mind the issues are more behavioural. Court staff want courts to be open but they have got into some bad habits and arcane procedures. Much could be done with proper leadership signals and setting out the fundamental elements in plain English. So I offered to write down a simple charter for transparency in the courts, of the sort that the Secretary of State and the Senior Presiding Judge could publish as co-signatories and might fit on one side of paper.

With apologies for my lack of precise legal terminology here is a draft, for the way in which the Senior Presiding Judge and Secretary of State for Justice should set out the following basic principles of openness and transparency for courts of all types. This could also apply to tribunals and coroners’ courts with minor adaptation.

Draft Courts Transparency Charter

Courts are open to the public and the media, with only narrow exceptions. This is at the heart of delivery of justice in a modern democracy and a proud national tradition. The government, the judiciary and people who work in courts want courts to be open transparent and comprehensible to the public and the press. But the courts over hundreds of years have evolved into a complex system that is hard for outsiders to understand.

In the interests of transparency and confidence in the justice system, people should be able to find out easily, on the internet:

- what cases are expected to come up in a court from the time that they are scheduled

- name, address and specific charges in all cases available from the time the case is scheduled (see ‘criminal cases’, below)

- the full names, including first names, of judges, prosecution and defence lawyers, witnesses, and other professionals who speak during proceedings (e.g. magistrates’ clerks giving legal advice) from when they are known

- judgments handed down from the end of the working day on which the case is concluded

- next stage of the case

The longstanding openness of courts must not be compromised by data protection or copyright. In particular, well meaning but misplaced concerns about the Data Protection Act 1998 and copyright must not stop the recording and transmission of information presented in open court.

All the above is subject to contempt of court and protection of vulnerable defendants and witnesses – exceptions to immediate transparency that are fundamental to the efficient effective functioning of the justice system. Case information should be flagged where restrictions apply and those restrictions set out in writing.

People who use information illegally or irresponsibly against the interests of efficient, effective justice or in such as way as to compromise the vulnerable may have their access to information withdrawn.

It should be assumed that all information is available to the press and the public, apart from the general exceptions above.

The best courts already meet these principles; we would like all courts to do so.

Criminal cases

In criminal cases, the following basic information should be readily available:

- The full spelling of a defendant’s name.

- Their date of birth and full home address, including door number and postcode.

- The charges against them (including an opportunity to read them).

- Written copies of any reporting restrictions applicable in the case.

Charges should be set out in the form used in Magistrates court – ‘On 23/07/2011 at Oxford Street, London, assaulted Joe Bloggs contrary to section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988’

Moving forward

Since I first published this Charter online in November 2011, I have discussed many of the issues with experts. There are numerous issues that bear upon simple transparency, each of which requires teasing out:

- Contempt of court or information that might prejudice a trial leading to reporting restrictions.

- Protection of vulnerable people such as children, some victims and witnesses.

- Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 – this gives people a basic right to be forgotten as their convictions become ‘spent’. This can be important for rehabilitation and manifests as a removal of the need to declare a crime in some circumstances and ultimately a removal of the record.

- Data protection and privacy; significantly, the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) says that in respect of courts data this will be applied in the context of the ROA 1974, which implies a societal resistance to an indelible record. Very detailed personal information tends to be read out in court such as full name, address and date of birth.

- Copyright; judges, barristers etc. own the copyright to their judgements and argument with no practice in place to waive that, nor grant licences for reuse.

- The lack of a legal underpinning for the traditions of open justice.

- IT systems; it is very simple and very cheap today to publish basic documents to the web of the sort produced in courts. But we need to understand what is held in MOJ data systems. A simple start would be to experiment with a court that has a presiding judge or magistrate and chief clerk that want their court to be as open as possible.

We have not as yet seen an attempt to work through this stack of issues. I am concerned that tackling these issues one at a time will entail bureaucratic inertia, which risks steadily undermining the tradition and practice of open justice. Open justice is sufficiently valuable in society such that we need rapid, decisive action to reaffirm our national commitment and re-establish open justice for the modern internet age.

Given that we have had open justice for centuries, there is a good case for putting the burden of proof of harm upon people who might seek to constrain open justice. This requires decisive action by leading judges, the Lord Chief Justice and the Senior Presiding Judge, and the Secretary of State of Home Secretary along the lines of the draft charter.

(c) William Perrin. This is an extract from Justice Wide Open, a collection of working papers published in June 2012 as part of the ‘Open Justice in the Digital Era’ project at the Centre for Law, Justice and Journalism, City University London, http://bit.ly/openjustice.