Revealed: Why the police are failing most rape victims

Recent acquittals in celebrity sex cases give the impression that most rape allegations reach court.

In fact, despite a decade of policy reforms, the chances of any rape complainant seeing their assailant convicted remains stubbornly low. In the last two years the number of suspected rapists charged and prosecuted has fallen, despite an increase in reported rapes.

An investigation by the Bureau, drawing on hitherto unpublished research from within the Metropolitan Police, reveals the prejudices behind these statistics – prejudices which mean that for some women, rape has effectively been decriminalised.

At King’s College Hospital in South London the Accident and Emergency department and the Haven, a specialist unit for victims of rape and sexual assault, are just a few minutes’ walk from each other.

But for one rape victim who was taken to A&E by her sister in March 2013, the Haven might as well have been behind a 20ft electrified wall.

Neither she nor her sister – we’re calling them Ella and Beth to protect their identities – were even aware the unit existed. ‘I took my sister to A&E because I didn’t know where else to go,’ says Beth.

That shouldn’t have been a problem.

The women were surrounded by professionals who knew the Haven was just around the corner. Staff working in the Haven are specially trained to carry out forensic examinations and to provide everything else that Ella might have needed, from emergency contraception to counselling to setting up an informal meeting with a police officer.

Despite this, and despite clearly fitting the criteria for referral to the unit – she had told her sister the rape had occurred the day before and she was complaining of abdominal pain – Beth says they were not told about the Haven, nor was Ella examined internally. Instead A&E staff suggested Beth should call the police.

The pair were taken to a police station, where they had a further lengthy wait before officers decided Ella had not been raped and sent her home.

Ella never received an internal examination and neither was she offered any kind of specialist support although, Beth says, she was extremely distressed by the rape. The trauma affected Ella’s behaviour – afterwards, she washed herself obsessively.

‘The failure to refer had a huge impact on my sister who had already been through an awful ordeal, as well as on her family and myself, because we had to deal with the impact on her,’ says Beth.

A spokesman for the Haven said he was unable to comment on the details of the case but said that where police were called referral to the Haven became the police’s responsibility.

In a statement, he said: ‘When someone who has been raped or sexually assaulted attends our emergency department, our clinical teams must carry out medical assessments to ensure that they do not need ongoing care in the acute hospital.

‘They are triaged as quickly as possible and offered the option to speak to the police. If they do want to talk to the police, the police then take the lead on collection of forensic evidence and referral to the Havens.’

One factor played a crucial role in Ella’s treatment – or lack of it.

She has learning difficulties and autism.

With the help of her sister Ella managed to give a clear account of what had happened to the A&E doctor, including a detailed account of oral and vaginal rape.

But after leaving King’s she was interviewed alone by police, who decided, because she was unable to communicate clearly, that she had only had oral sex.

Even if Ella had only been orally raped, she should still have qualified for a Haven referral.

Beth says she was later told by the police that when the man her sister had accused was interviewed by police he admitted to having sex, but he said it was consensual and the police decided to take no further action.

‘My sister’s difficulty in communication and understanding – and given that she had said something different while in the hospital – meant the police should not have treated what she said in the interview as set in stone,’ says Beth.

‘A thorough examination should have been done as a precaution.’

‘The man who assaulted my sister had been asked to leave his job a short time before the rape for making inappropriate comments,’ she adds.

Officers told her they couldn’t put Ella through the courts as she was a vulnerable person.

Despite recognising that vulnerability, they did not carry out a capacity assessment before interviewing Ella or arrange for her to be supported during the interview.

‘It really does cause me great upset when I look back at the complete faith I had in all services involved,’ Beth says.

The Bureau approached the Metropolitan Police for comment on 7 February. At the time of publication, no response had been received.

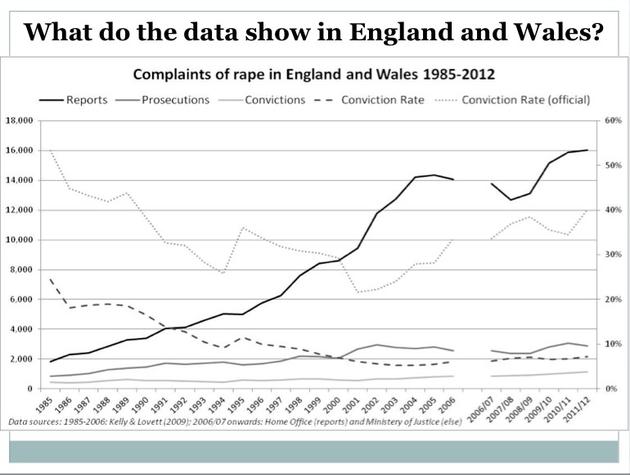

Despite soaring reports of rape for the past decade detections, prosecutions and convictions in rape cases have not kept pace – and attrition, the rate at which cases drop out of the system, has gone from bad to worse.

Only around 15% of rapes recorded by police as crimes in 2012/13 resulted in rape charges being brought against a suspect.

Two thirds of rape complaints dropped out of the criminal justice system before they were sent to prosecutors.

And this was not because a suspect had not been identified – in the majority of cases, the identity of the alleged rapist was known.

Source: Professor Betsy Stanko, assistant director planning and portfolio, Metropolitan Police

Source: Professor Betsy Stanko, assistant director planning and portfolio, Metropolitan Police

Detectives’ decisions on rape cases are rarely subject to outside scrutiny. Unlike the CPS, the police do not record their reasons for dropping cases consistently and there is no centralised data collection.

Now, internal documents obtained under Freedom of Information and new unpublished research shared with the Bureau can shed light on the process within the country’s largest police force.

They show that most people reporting rape to the Metropolitan Police are vulnerable to sexual attack – and that these same vulnerabilities mean their cases are less likely to result in a suspect being charged.

The author of the research, an academic turned senior civil servant who has been studying rape for a decade inside the Met, is calling for radical change.

Professor Betsy Stanko, the Met’s assistant director of planning and portfolio, says some categories of the most vulnerable rape victims, such as those with learning difficulties, has effectively been decriminalised.

This is because of investigating officers’ focus on the victim’s credibility, which is seen as vital to proving whether there was consent to sex.

The professor wants police to concentrate instead on whether and how suspects exploited their victims’ vulnerability.

She contends that it is because policy and legal reforms have focused on consent rather than exploitation that such a high percentage of rape cases still drop out of the justice system before trial.

Former Labour Cabinet member Tessa Jowell said Professor Stanko’s proposal that officers focus on whether vulnerability has been exploited rather than whether consent can be disproved, was ‘a really important and powerful idea’.

‘It recognises trauma and the disruption that trauma creates,’ she said.

Failure to understand consent leads to cases being “no-crimed”

One document obtained by the Bureau, titled An Overview of Sexual Violence, was produced by the Met’s ‘evidence and performance unit’ in 2013.

It shows how various factors influence the chances of police dropping rape cases.

Around 13% of rape cases were dropped because officers initially recorded a rape but then decided no crime had occurred. These cases were recorded as a ‘no-crimes’.

Shockingly, cases were more likely to be classified as ‘no-crimes’ and dropped if victims did not understand the concept of consent than if there was evidence casting doubt over whether the offence took place at all.

Where police accepted a crime had occurred, cases where the victim lacked understanding of consent were less likely to be referred to prosecutors for charging decisions than cases where this was not a factor.

The document notes that a large proportion of cases dropped out because victims had withdrawn from the process – 36% of complainants withdrew.

It asks: ‘Have victims been given advice to withdraw?’

The data in the document was drawn from an analysis of 687 rape allegations made to the Metropolitan police during two months in 2012.

Professor Stanko’s team has been collecting data on allegations made during April and May each year for more than eight years.

Research shows cases involving victims with learning difficulties less likely to be referred to police

The professor, who is soon to join the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, is preparing research for publication in a peer-reviewed journal based on a sub-set of the 2012 data.

She has shared some early findings with the Bureau.

Her research, which will be discussed at the London School of Economics on March 11, found police were more likely to find that a crime had not occurred when victims with learning difficulties and mental health problems reported a rape than when these characteristics were not present.

Those with learning difficulties were 67% less likely to have their case referred by police for prosecution than those without. Mental illness reduced the chances by 40%.

‘These women face almost unsurmountable obstacles to justice,’ Professor Stanko says. ‘Their rape is highly unlikely to carry a sanction, and in that sense, it is decriminalised.’

Alcohol consumption prior to the attack reduced the chances of referral to prosecutors by 45%, as did a history of consensual sex with the suspect.

‘If a victim has mental health problems or is in a current relationship with the suspect then the most likely outcome is that the case will be dropped,’ Professor Stanko adds.

‘Victim vulnerabilities effectively protect suspects from being perceived as credible rapists.’

Her research mirrors a study by the University of Bristol published last year ,which tracked rape cases in three police forces areas in the North East of England.

The study found only around a third of cases where the victim had mental health problems resulted in arrest, compared to half of the cases where no mental health issues were recorded.

Professor Stanko also found very high levels of victims disengaging from the police.

Victims who had previously been in a relationship with or had previous consensual sex with the suspect were twice as likely to withdraw their allegations as those who had not.

‘Some of this lack of co-operation may be due to the way they feel they were treated when reporting the allegation,’ the professor said.

The Bureau has also obtained an internal report by James Patrick, a Metropolitan police constable, written in September 2013.

The report concerns recording of sexual offences within the Met.

The PC, who has since given evidence on manipulation of crime recording to the public administration select committee, is facing misconduct charges in relation to whistleblowing on crime statistics.

The report refers to a sample of 20 rape allegations that the police had recorded as ‘no-crimes’, meaning that officers decided a crime had not occurred.

A review of the sample by a Met performance team found that nine cases (45%) were classed as vulnerable according to an official definition.

In other words the victim was under 17, had mental health issues or a disability of some kind or the quality of their statements was likely to be affected by fear or distress about giving evidence.

When other factors were included in the definition of vulnerability, such as the victim having consumed alcohol or taken drugs beforehand, the figure rose to 75%.

20% of the cases involved domestic violence.

60% of the victims had withdrawn their allegation, stating that sex was consensual.

The double-bind: the vulnerable are targets but are not believed

Since Laurie Lee described his friends’ plan to rape a girl who was ‘daft in the ‘ead’ in his classic memoir of the 1920s Cider with Rosie, various studies have shown people with learning difficulties or mental illness are more likely to suffer sexual attacks than those without.

And a stream of police officers have been sacked and prosecuted for explicitly targeting vulnerable women for sexual purposes.

In total more than 80% of victims in Professor Stanko’s sample had characteristics that leave them vulnerable to sexual attack, including 18% with a mental health problem.

A significant body of research has observed that these characteristics are exactly the same as those deemed by police to undermine the victim’s credibility as witnesses. Credibility is vital in a case that turns on lack of consent.

Professor Stanko has been analysing the investigation of rape within the Met for ten years. Her research team has looked at the outcome of every rape allegation reported in April and May for over eight years. The Metropolitan Police itself has used this research to explain a decline in the percentage of rape cases being charged and prosecuted.

‘The rules of evidence regarding the defence of consent when over 60% of allegations take place in private and the reliability of victims where over 80% have at least one identified vulnerability in their lives, is reducing the likelihood of cases reaching the necessary evidential test [for prosecution],’ two senior officers in the Met’s specialist investigation team wrote in a review of sexual offences in late 2011.

They added: ‘Victim vulnerability factors continue to feature mental health problems, drug and alcohol use, young age and abusive relationships.

‘All these factors create a double bind of increasing the risk to the victim while also impacting on attrition within the criminal justice system … making them and their evidence less robust when scrutinised in the light of court processes’.

Action points emanating from the review did not include any plan to address this or what the findings meant in terms of investigation, training or decision-making.

Professor Stanko joined the Met in 2003 from an academic post at Royal Holloway, University of London and initially at the request of the then commissioner Sir Ian Blair, began researching the force’s handling of rape allegations.

What’s startling about her findings, she says, is how little has changed.

‘The profile of victims reporting rape in London hasn’t significantly changed in eight years,’ she says.

Around a third are under 18, the vast majority know the suspect, between a quarter and a fifth are or have been in an intimate relationship with their assailant.

Most attacks take place in a private home and the victim has drunk alcohol or taken drugs in around a third of cases.

While policing has changed – cases are now much less likely to be categorised as ‘no-crimes’ than they were, barriers simply come into play at different stages, she argues.

‘The overwhelming majority of rapes still go unreported. But we are not learning from those allegations that do reach the police.’

The Merits-Based Approach

In 2009, the High Court ruled that the CPS had unlawfully discriminated against a victim of a serious assault by dropping his case purely on the grounds that he had mental health problems and therefore could not be considered a reliable witness.

The judge said that in ‘date rape’ and other cases which relied on witness accounts, prosecutors should not try to predict the outcome of cases based on past experience of similar cases. Neither should they require witness testimony to be corroborated before proceeding.

Instead, they should ask themselves whether, on balance, the evidence is sufficient to merit a conviction taking into account what is known about the defence case.

In 2010 all chief Crown Prosecutors attended a course in the new ‘merits based approach’ to rape cases. Police forces were also expected to adopt this approach.

Alison Saunders, the then chief crown prosecutor for London gave a speech in 2012 explaining the new approach:

‘Though past experience might tell a prosecutor that juries can be unwilling to convict in cases where, for example, there has been a lengthy delay in reporting the offence or the complainant had been drinking at the time the rape was committed, these sorts of prejudices against complainants should be ignored for the purposes of deciding whether or not there is a realistic prospect of conviction.

In other words, the prosecutor should proceed on the basis of a notional jury which is wholly unaffected by any myths or stereotypes of the type which, sadly, still have a degree of prevalence in some quarters.’

The expectation was that the CPS would authorise more charges for rape and send cases to court which historically would have failed evidence tests.

Coverage of the recent celebrity sex trials, which have relied heavily on witness evidence, gives the impression this has been happening.

In fact, CPS data shows numbers of rape cases charged and prosecuted have fallen since 2010.

What changed after Savile?

Media storms over Jimmy Savile and child grooming cases extracted solemn promises from police and prosecutors to change the way they dealt with claims of historic sexual assault and child sexual exploitation.

But Professor Stanko believes the lessons learned from Savile are not being applied to more typical sex crimes.

Recent rape claims are still dropping out of the criminal justice system in the thousands for the same reasons that lead to the Savile victims being silenced, she says.

‘Savile’s exploitation of vulnerability is considered separate from ‘typical’ rape or sexual abuse.’

Revelations that authorities had steadfastly ignored complaints because of the youth and vulnerability of the complainants lead to the CPS publishing new guidelines on child sex abuse cases in 2013.

A serious case review into one of the Rochdale grooming cases had noted that a rape complaint by one girl had been dropped on CPS advice because she was deemed likely to have consented as she was, as the CPS lawyer put it, ‘known for going with men’.

‘The advice was based ‘very considerably on consent by (the girl) although given that she had also been physically assaulted, sustaining injuries, the issue of consent could not have been an issue.

‘… the CPS focus appeared to be in looking for failings in the prosecution case rather than considering the weaknesses in the case for the defence,’ the review said.

In the new guidance, prosecutors were told to focus on the overall credibility of an allegation rather than the perceived weakness of the person making it.

The move was announced by the then Director of Public Prosecutions Keir Starmer as ‘the most fundamental attitude shift across the Criminal Justice System for a generation’.

No similar change was announced with regard to adult rape cases.

Asked why the attitude shift was limited to child cases, the the CPS said existing guidance on adult cases already warned prosecutors to be aware of myths and sterotypes around how sexual offence victims were handled.

The CPS has also excluded vulnerable adults from a new protocol requiring police and prosecutors to share and seek information about vulnerable youngsters with and from social services, local authorities and family courts.

The 2012 HMIC report that recommended the development of the information-sharing protocols did not mention that they should only be applied to child cases.

And minutes of a meeting of the Rape Monitoring Group in 2012, a group chaired by HMIC and whose members include police chiefs, officials from the Home Office, CPS and Attorney General’s Office as well as the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, note that ‘the desirability of including vulnerable adults in this protocol was commented on’.

In the end, they were not included.

For adult rape, questions around consent, rather than vulnerability, continue to dominate, and while it is too soon to tell whether the change of approach to child cases is working in one case uncovered by the Bureau involving a 16 year old girl, a presumption of consent is still trumping evidence of injuries.

‘The debate, policies and law reforms continue to address issues of consent – the legal line separating sex from rape,’ says Professor Stanko.

‘Exploitation is seldom recognised, though it is critical to how rape happens.’

A recognition of this exploitation must be at the heart of any reform, she says. Anything else is ‘tinkering around the edges’, which will be unlikely to produce real change.

And change is still urgently needed.

Case study: Mother was told 16-year-old daughter ‘knew what she was doing’

Sixteen years old Josie (not her real name) was penetrated so violently that doctors had to give her a general anaesthetic before they could finish examining her.

Medical records note bruising on her neck, both breasts and groin, and that she was bleeding heavily from two internal tears, according to detailed letters written to the police by the woman’s lawyers.

Despite this evidence, police dropped the investigation into her assailant because she had initially given an incorrect account about her meeting with him.

The teenager, who was a virgin at the time of the attack in October 2012, had known the man for two months after meeting him at a store where she worked and had exchanged texts with him.

As the weeks went by his texts became more frequent and he began to respond angrily when she failed to reply as quickly as he wanted. She eventually agreed to meet him but, anticipating disapproval, told her mother she was going shopping with a friend.

The man took her for a drive, then to his flat where she was assaulted.

After leaving the flat she went immediately to hospital, which notified her mother and the police.

In both Josie’s initial statement to police – given while still at the hospital and in a state of shock – and in her formal interview with specialist officers she gave the account of her movements she had previously given to her mother: that she had gone shopping with a friend.

She said she had met her assailant by chance.

At the time of the formal interview officers had established that the meeting had been pre-arranged, and they informed her at the end of the interview that the case would be discontinued.

‘I wanted to explain before the interview that I had not told the truth because of what my mother would say,’ Josie told the Bureau.

‘But when I arrived everything was so rushed, I went straight into the interview room. The policewoman was not at all sympathetic, she talked down to me and asked questions without letting me answer. I knew there were two other police officers watching. It felt like I was the criminal.’

While Josie was being interviewed, her mother was questioned by officers about what her daughter had been wearing on the day of the attack. She was told that her daughter had ‘known what she was doing’ and that her injuries were consistent with first time sex.

The police also quoted the suspect as stating that Josie had sent him flirtatious text messages indicating a desire to have sex with him. Josie denies this.

According to her lawyers police officers never bothered to read the full exchange of messages between the pair.

Josie and her mother complained about the police investigation. The complaint was investigated – and rejected – by a senior detective in the same team as the original investigating officer.

Josie then appealed to the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), which instructed the force to reinvestigate.

The outcome of this fresh investigation was the same as the first. A further appeal to the IPCC is pending.

National data shows little long-term improvement

Although numbers of rape convictions have crept up over recent years (there were 1,142 guilty verdicts in 2011/12, up three percent on the year before) so have numbers of recorded rapes. The proportion of police-recorded rapes that result in a rape conviction has improved two percentage points in the last nine years.

The CPS records ‘rape flagged’ prosecutions and convictions, which include convictions for offences other than rape arising out of a rape allegation.

As Baroness Stern pointed out in her 2010 review of rape and the criminal justice system, the conviction rate improves to around 12% if these other offences are included.

However for the last two years numbers of these ‘rape flagged’ prosecutions and convictions have fallen.

And the Home Office has acknowledged that numbers of cases resulted in charges or that are otherwise cleared up (solved, or ‘detected’ cases) are not keeping pace with increasing numbers of rapes being reported to police.

‘Although the number of rape offences detected has increased since 2007/08 (up by 17%), the increase has not kept pace with the increase in recorded offences.

As a result, the detection rate for rape has fallen from 26% to 23% between 2007/08 and 2012/13,’ it said in its latest crime bulletin.

In most cases classed as unsolved, the cases the suspect is known or identified meaning the case could potentially be solved. Many of these ‘unsolved’ cases were in fact concluded by police officers.

Most cases end at the policing investigation stage and never reach prosecutors, let alone a jury.

Around 16,000 rapes were recorded by police in the last financial year. Only around a third of this number sent to prosecutors, with the rest dropping out before being formally considered for charge. Around 15% of the recorded offences ended in charge.

‘Why is the detection rate so low given the suspect is known or identified in most cases? Why is such a small percentage prosecuted?,’ Professor Stanko asks. ‘Why is attrition so persistently high and conviction so rare? It is a question of attitude.’

Focusing investigations on the exploitation as opposed to the victim’s credibility will not always lead to a successful prosecution, she admits.

‘But something has to be done.'

Prejudice trumps policies

Harriet Wistrich, a lawyer who has successfully sued the Metropolitan Police on behalf of victims of convicted serial rapist John Worboys, agrees. She says the Met Police has some very good policies on investigating rape ‘but they simply don’t translate into practice.’

The women were given spiked champagne by taxi driver Worboys which left them unconscious, allowing him to assault them, but also meaning they had an unclear recollection of what had happened.

One officer’s response to a victim was that it was unlikely a cab driver would have alcohol in the car.

‘The number one principle of those investigating has to be that you believe the victim until you find evidence that they are not telling the truth,’ Ms Wistrich says.

While senior officers acknowledged the importance of that principle there was ‘little will or concern’ to ensure it was consistently applied, she added. ‘There’s no enforcement.’

The women she is acting for were attacked by Worboys four years apart but experienced similarly poor treatment by the police.

‘These women suffer terrible feelings of guilt. Because they were not believed, Worboys was left free to attack more women. They feel responsible. When the police give evidence they don’t seem to show a similar sense of responsibility.’

From reporting to charge: What we don't know

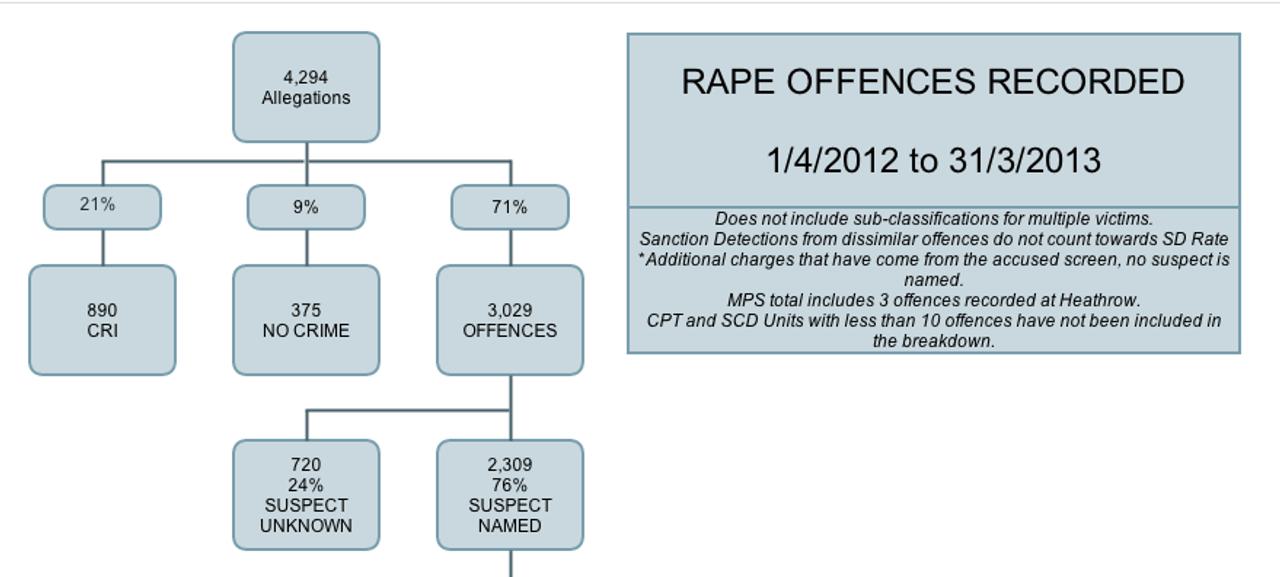

Click here to see the complete police diagram showing outcomes of rape reports

An internal diagram released to the Bureau under Freedom of Information shows that within the Metropolitan Police, 408 out of 4,294 rape allegations made in 2012/13 (9.5%) were ‘detected’ (charged, cautioned, or dealt with) with a further 97 cases (3%) still outstanding.

The diagram shows the main points of case attrition, or drop-out.

In 2012/13 there were 4,294 allegations of rape.

- 29% of cases dropped out because they were not recorded as crimes

- 17% of cases stalled because a suspect was not identified

- 18% of case ended because the suspect had been identified but not arrested, mainly due to insufficient evidence (6% of all allegations) and the victim being unwilling (10% of all allegations)

- 19% of cases were dropped after arrest, mainly due to insufficient evidence (11% of all allegations) and the victim being unwilling (4% of all allegations)

However this diagram does not tell us the whole story, and neither does Professor Stanko’s research, which is based on analysis of crime reports.

This because some cases are dropped before they ever enter forces’ crime recording systems.

Police crime reports may also include incomplete information and conflict with the victim’s recollection of events. Retraction statements may have been provided under pressure.

A spokesperson for the Met said: ‘We absolutely recognise that one of the factors in sex offences is any vulnerability of the victim, which can be either permanent or temporary.

That is entirely the reason why we have SOIT [sexual offences investigation trained] officers to support and interview victims of rape, so they can understand the individual needs of the victim as they deal with the investigation. Every victim needs to be treated in a way that meets their individual needs.

We always try to identify any vulnerability factors with victims, as given the predatory nature of these crimes it is often those very factors that lead the offender to select the victim. However, the issue of consent is at the heart of the offence of rape and investigations have to prove the consent issue if there is to be a successful prosecution.

Over the last three years there have been an increased number of charges from 2009/2010 there were 428 charges, and FYTD April 2013 – Feb 2014, 640 charges. Since April 2013 there has been a 30 per cent increase in the number of allegations of rape, a sign of increased confidence that people are more willing to talk to us.”