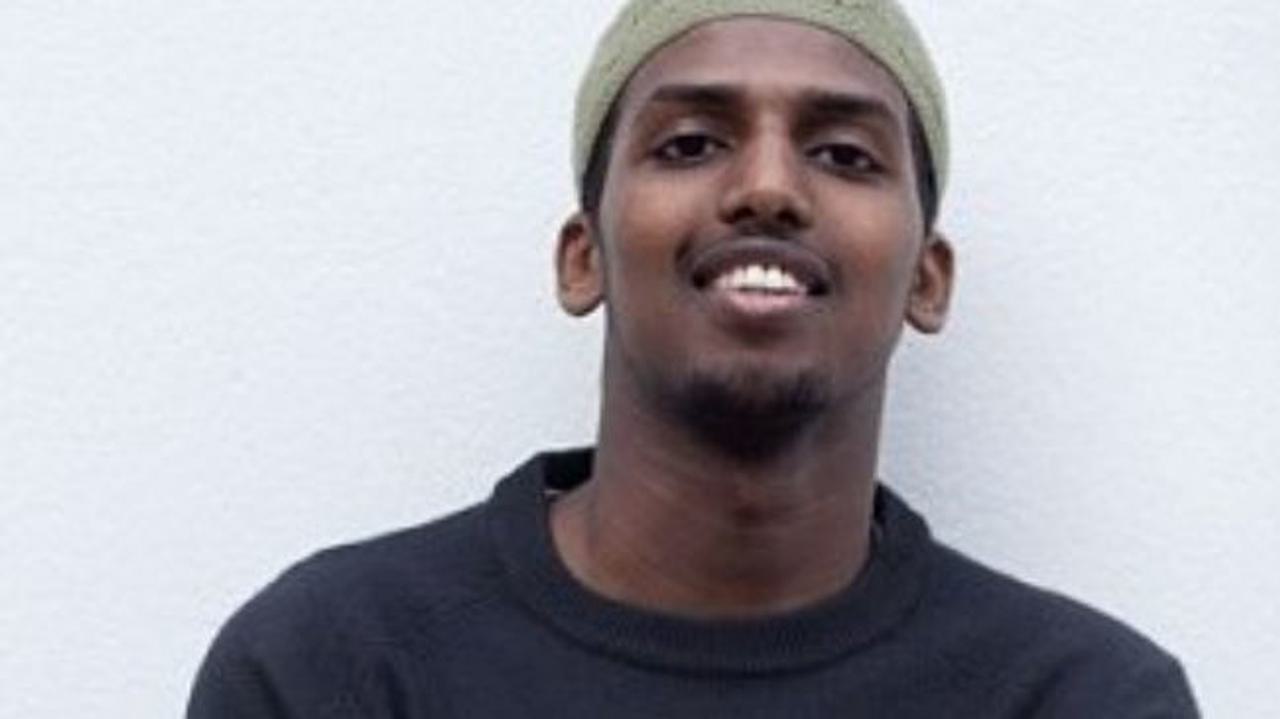

Former Briton Mahdi Hashi now jailed by New York judge for al Shabaab terror charges

Former British citizen Mahdi Hashi was yesterday sentenced to nine years in prison at a New York court for supporting the terrorist organisation al Shabaab, three years after being secretly taken to the US from a Djibouti jail.

Hashi, 26, who was stripped of his British citizenship in 2012 by Theresa May, has spent the past three years in solitary confinement in a New York prison. He had pleaded guilty in May last year to conspiring to provide material support to al Shabaab in Somalia several years earlier.

During sentencing yesterday U.S. District Judge John Gleeson said the facts were “complicated”, accepting in part Hashi’s position that he joined al Shabaab not to engage in violent attacks but because he thought it could restore peace to war-torn Somalia, according to Reuters.

“I believe you believe this organisation you joined was dramatically different than what you thought or hoped it would be,” he said.

Hashi’s two Swedish co-defendants, Ali Yasin Ahmed and Mohamed Yusuf, were each sentenced to 11 years for conspiring to provide material support to al Shabaab two weeks ago.

The three men had been held in Djibouti in late 2012 before being brought to the US to face terror charges.

Hashi’s sentencing is the latest development in a saga that has been running for more than three years. All three men were accused by the US of terror offences, and all three have alleged they were abused at the hands of their captors in Djibouti.

The Bureau has been covering Hashi’s case as part of a long running investigation into the UK government’s use of controversial citizenship stripping powers.

Somali-born Hashi arrived in the UK with his family as a five-year-old in 1994 after they fled the civil war in their native Somalia and claimed asylum. At the age of 14, he became a British citizen.

After living in Egypt to study Arabic when he was 16, Hashi claimed he was “harassed” by British intelligence agencies and he and several others went public, telling the Independent in 2009 they were being pressured into spying for MI5. Shortly after this he travelled to Somalia to care for an unwell grandmother, according to his own account.

By June 2012 Hashi was still living in Somalia, now married and with a son, when his parents called to tell him a letter had arrived containing a deprivation order from the home secretary. The letter stated his British citizenship was being removed on grounds he was “involved in Islamist extremism”.

Hashi claimed he then left Somalia as there was no British embassy there from which he could launch an appeal, which under the law he had to do within 28 days. That summer he travelled to Djibouti, where he was detained by authorities along with Ahmed and Yusuf.

In legal filings the US government said Hashi, Ahmed and Yusuf were “captured” by foreign authorities on suspicion of being terrorists.

In court documents filed in their US case, the three later alleged they had been threatened with sexual abuse and torture while imprisoned in Djibouti.

Documents filed in relation to Hashi’s case by his US attorney, Mark Demarco, stated Hashi was detained “in a secret Djiboutian facility under extremely harsh conditions” and was subjected to “illegal interrogation” by US intelligence officials.

This “illegal interrogation” was just months after Theresa May had stripped him of his British citizenship. While Hashi said he was trying to get to Saudi Arabia to lodge his appeal, the US government said he was on his way to Yemen when he was detained by authorities in Djibouti.

Hashi was held incommunicado for months, and it wasn’t until a fellow inmate was released and contacted his family that they found out where he was. The family contacted the British Foreign Office, which, according to Hashi’s father, told them his son was “no longer a British national, and as such has no right to receive Consular assistance”.

Held in Djibouti and taken to the US, Hashi did not lodge an appeal against Theresa May’s deprivation order within the 28-day limit. His lawyers later appealed to the Special Immigration Appeals Commission after the deadline had passed.

Siac dismissed Hashi’s appeal a year ago, saying it was “out of time” and that Hashi “fails to show it would be unjust not to extend time for the appeal”.

His lawyers are preparing to appeal Siac’s decision. A hearing is expected at the Court of Appeal in October.