Shortage of black teachers, data reveals

Black and ethnic minority teachers are still significantly under-represented across staff rooms in England, new analysis by the Bureau has revealed.

Figures obtained from the Department for Education (DfE) show just 7.6% of teachers in state schools in England are people of colour compared with almost 25% of pupils.

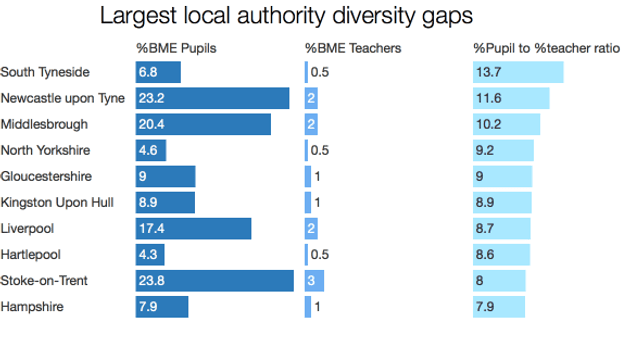

In some local authorities the situation is so bad that there would need to be a more than tenfold increase in the number of BME teachers for staff to reflect their pupil populations.

When it comes to school leadership the gap widens even further – 97% of English state school headteachers are white.

Responding to the findings, Chris Keates, general secretary of teachers union NASUWT said: “It is clearly unacceptable and it is also disgraceful. Education is such a powerful determiner of life chances. All children and people working within education should be treated with dignity and with access to equality. That clearly is not happening.”

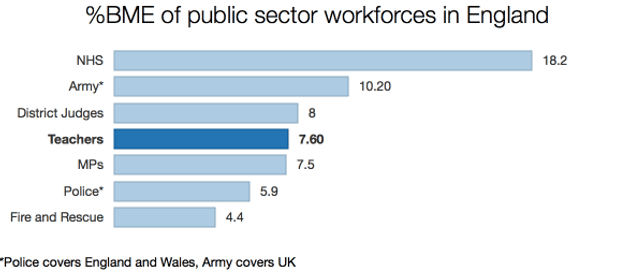

The House of Commons is widely derided for being too white, but the Bureau’s analysis shows the racial diversity of teachers in England is almost identical. The proportion of BME Members of Parliament serving English constituencies is 7.5%, just a tenth of a percentage point less than the proportion of BME teachers.

Central Bedfordshire, City of London and Haringey perform best for diversity of all the authorities that contain at least 10% BME pupils. Each has a pupil/teacher diversity ratio of less than two.

However, the data shows that not a single authority has achieved a diversity of teachers that matches that of pupils.

Related story: Mapping the teaching diversity gap

The reasons staff in UK schools do not represent their pupils’ diversity are complex, according to teachers and experts.

“There is a lack of fair and transparent recruitment procedures for interviews and a lack of awareness training for schools on equality issues,” Keates said.

Discussing wider issues of pay, pay progression and promotion, she added: “All our evidence shows that there is an unfair system in place and it is doubly unfair for BME teachers.”

Cultural attitudes towards different types of work are also a factor, according to Monika Bhattacharya Quigley, a teacher of Indian origin working in Newcastle. “Amongst the middle class settled [BME] population – the shop workers, professionals and business people – teaching is not valued,” she said. “Graduates from those backgrounds aim to become doctors, engineers or bankers: careers which are seen as more lucrative and better regarded.”

Alistair Ross, Emeritus professor at London Metropolitan University in the Institute of Policy Studies in Education, agrees.

“Amongst the Asian community teaching is thought not to be regarded highly,” he said. “Law and medicine are considered much more reputable professions to go into from your family’s perspective. But I would expect that pressure to weaken as generations move on.”

Figures obtained by the Bureau show that only 13% of postgraduate trainee teachers in the 2014/2015 academic year were BME, compared with 35% of people studying medicine, dentistry and law at higher education institutions.

Leora Cruddas, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders, said young people from BME backgrounds did not have enough role models in teaching to inspire them to take up the profession.

“Part of the solution is to actively encourage young people from BME backgrounds to consider teaching as a valuable profession and at the same time, to talent spot and nurture BME teachers to consider taking up leadership positions,” she said.

Official statistics

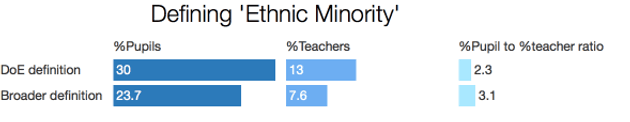

The DfE’s published data shows a different picture to the Bureau’s – because its definition of people belonging to an ethnic minority includes anyone who’s white but not British. Polish or French teachers and pupils, for instance, are counted as minority ethnic according to this categorisation.

Using that definition, there is a smaller diversity gap – 13% of teachers nationally are BME compared to 30% of pupils. Half of those teachers are White Irish or White (other).

The DfE says it follows guidance from the Office of National Statistics. To group White Irish and other white non-British pupils into a single white category would cloud the figures, it said – obscuring the total number of ethnic minority pupils and teachers in schools.

The NHS and police, however, do not count non-British white staff as being from an ethnic minority.

Racism in schools could also put young people off going into teaching as a profession, said Ross, though such a theory had only ever been put forward anecdotally.

Surveys carried out by NASUWT and the NUT certainly suggest it’s an issue. A poll conducted by NASUWT last November at the largest ever gathering of BME teachers in the UK found 62% believed schools did not treat BME pupils fairly and 60% believed schools didn’t respect BME teachers.

In 2014 a major NASUWT-commissioned study into the equality impact of reforms to teacher pay found BME teachers tended to be paid less than white teachers and were much less likely than white teachers to hold senior leadership positions.

“These issues have to be addressed through coherent equality strategies in schools, fair and transparent recruitment practices and the collection of robust data on promotions so that the scale of this problem can be brought into the open and dealt with.”

Case study: Adrian Rollins

After his decade-long career as a county cricketer ended in 2002, Adrian Rollins moved into education, teaching PE and maths. 14 years later he’s an assistant headteacher at a secondary school in Derbyshire. As a black teacher, he is breaking the mould: people from BME backgrounds comprise 7.6% of the teaching workforce, yet they only make up 3.1% of headteachers.

Rollins believes the lack of diversity amongst school governors, who make hiring decisions on headteachers, may be partly responsible, by perpetuating assumptions that heads will be white and male.

“There have been occasions when I’ve asked myself how that person got that job,” he admitted. “I’ve been in schools where there are good black teachers and heads of department, but none in senior leadership.

“People expect a head teacher of a secondary school to look a certain way: like a white man. Women are in a similar situation: you find schools where most of the teachers are women but the head is a man.”

He added: ““There are lots of training programmes for BME teachers on how to progress. There should be training for governors too.”

In his own case, he believes his ability to forge good relations with students may have counted against him.

“I’ve never thought that I didn’t get a job because I was black,” he said. “It was more that I was seen as ‘operational’ – a good head of department, with good relationships with students – but lacking that strategic experience for senior leadership.”

While there may have been a racial element to this, he says it is impossible to tell either way.

“Nobody is going to come up to you and say we don’t want you because you’re face doesn’t fit, because you’re black. Racism isn’t overt; it’s very subtle. But the stats show clear differentials.”

The diversity of schools’ governing bodies also needs to be addressed, according to unions and a 2014 study by the National Governors Association. It found respondents were overwhelmingly white and tended “not to appoint headteachers who reflect the diversity in the ethnicity in their school’s community.”

The length of time that headteachers tend to stay in their posts meant that it was impossible to really measure whether governing bodies were discriminating against candidates according to race, said Ross. “So you can’t put your finger on a single appointment and say “that’s a racist decision” but if you look at the disparity of outcomes nationally then there is the presumption that racism, perhaps unwittingly, is taking place.”

A DfE spokesperson said: “We trust school leaders to recruit the right teachers for their classrooms but we are clear that good teams should reflect the diversity of their communities. The percentage of Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) teachers is at its highest level on record, and the percentage of BME trainees on postgraduate training course continues to rise.

“We are investing millions of pounds to attract the best and the brightest into the profession, regardless of their background, and we’re also expanding Teach First to get more top graduates into teaching in some of the most challenging parts of the country.

“By supporting schools to recruit and retain the high quality teachers they need, we will ensure every child has an equal opportunity to reach their full potential.

The Bureau newsletter

Subscribe to the Bureau newsletter, and hear when our next story breaks.