Intensive farmers get £70M in government subsidies in two years

The operators of industrial-scale livestock farms have received millions of pounds of public funds in the last two years, the Guardian can reveal, despite concerns over the spread of US-style factory farming across the British countryside.

Farms supplying some of the largest and most influential food companies that now dominate the UK’s meat and dairy sectors are amongst those receiving support.

A data analysis by the Guardian and Bureau of Investigative Journalism has found that recipients of almost £70 million in subsidies in 2016 and 2017 include individuals and companies running:

- Feedlot-style beef units, rearing thousands of cattle in outdoor yards

- So-called megadairies, with herds of up to 1,800 cows

- Intensive egg producers using cage housing systems

- Poultry megafarms and pig units which keep thousands of animals permanently indoors

- Livestock units that have been found guilty of pollution and animal health breaches

As revealed by the Bureau, the number of intensive pig and poultry farms in the UK has increased by more than a quarter in recent years. Coupled with a rise of intensive production in the dairy and beef sectors this has raised concerns over water pollution with livestock faeces, disease and animal welfare.

Opponents claim that smaller farms could be pushed out of business by the trend, leading to the takeover of the countryside by large agribusinesses, with a loss of traditional family-run units.

The data showed that individuals and companies linked to intensive poultry farms across the UK received the most money in subsidies, at £32m. The operators of pig and dairy factory farms were given £18m and £16m respectively, while the figure for intensive beef farms was £2m. The total sum received could be higher.

In many cases, subsidies are indirect, with a farmer receiving financial support for one aspect of their business - crop growing, for example - rather than the factory farm itself.

The shadow environment secretary, Sue Hayman MP, said the subsidy payments “were encouraging more, and larger, intensive livestock farms”.

“This is not the way to build a thriving and sustainable food sector,” she said.

Dr Taro Takahashi, a researcher at the University of Bristol and Rothamsted Research, said the payment of subsidies to intensive farms may be justifiable if they were found to be improving environmental standards.

“It is unreasonable to preclude megafarms from the public payment system purely because they are already large-scale,” he said. “The question, though, is whether these funds are indeed improving the environment and ecology of our countryside to sufficiently justify the investment - and research to date has been inconclusive either way. There is definitely an urgent need to examine this issue further.”

Labour has pledged to investigate the effects of megafarms on animal welfare and the environment, and to design post-Brexit farm subsidies that “move away from intensive factory farming and bad environmental practices”.

Dr Nick Palmer, head of Compassion in World Farming UK, said: “These astonishing findings fly in the face of the attempt to establish Britain as a world leader in welfare standards and to maintain a sustainable British farming industry in the uncertain years after Brexit.”

The industry says that strict controls on industrial-scale farms mean that disease, pollution and the carbon footprint can be kept to a minimum. They also point out that such farms can produce for consumers at a lower cost than small-scale farms.

The National Pig Association (NPA), which represents pig farmers, says only farmers operating mixed farms - for example, keeping livestock and growing crops - receive subsidies. Defra confirmed that farmers who only farm pig or poultry are not eligible subsidies where the animals are always kept indoors.

“We continue to disagree with the sentiment that ‘intensive’ production automatically equals poor welfare,” said Dr Zoe Davies of the NPA. “High quality well trained stock people and sufficient resource and vet support are the most important attributes which determine an animals welfare, not the number of animals present or the system within which they are reared. British pig welfare standards are some of the highest in the world and farmers take pride in providing affordable, quality food for all consumers.”

The British Poultry Council said that“ indoor poultry production does not attract subsidies under CAP or its proposed replacement.”

The sum of subsidies payments paid to those running intensive farms was calculated by cross-referencing registers of intensive UK farming operations for pig and poultry, and other databases of intensively-reared UK beef and dairy cattle, with the Defra register of Common Agricultural Payments payments made to farmers in 2016 and 2017.

Defra and the Environment Agency (EA) maintain a public register of all permit-requiring “intensive” pig and poultry farms, which are classified as such if they can house indoors at least 40,000 poultry birds, 2,000 pigs grown for meat, or 750 breeding pigs.

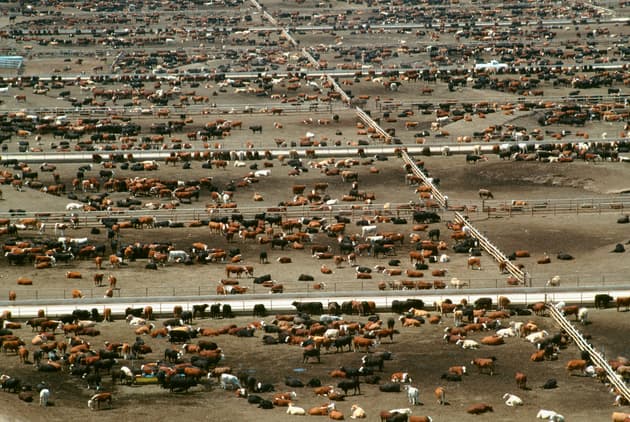

Will subsidies for intensive beef farming encourage US style feedlots (seen above) in the UK?

Glow Images/Getty

Will subsidies for intensive beef farming encourage US style feedlots (seen above) in the UK?

Glow Images/Getty

The database of intensive beef and dairy operations was compiled through earlier research by the Bureau.

The actual amount of subsidies is likely to be higher, principally because large numbers of pig farms in the UK are believed to fall below the size threshold for requiring a Defra/EA permit. Many such farms house their pigs indoors and would therefore be considered intensive by most experts, but are absent from the data.

The march of American-style “megafarms” or CAFOs - defined in the US as facilities housing 125,000 chickens for meat, 82,000 laying hens, 2,500 pigs, 1,000 beef or 700 dairy cattle - has previously been revealed in an investigation by the Guardian and the Bureau.

Most of these farms have gone unnoticed, despite their size and the controversy surrounding them, in part because many farmers have expanded existing facilities rather than seeking new sites.

Defra responded to the findings by pointing to the government’s plans for subsidies post-Brexit. “At the moment, Direct Payments are allocated according to the size of individual land holdings, not the way in which that land is farmed. Our proposed new system will move away from this, rewarding farmers for delivering public goods such as environmental protection and the health and welfare of livestock,” said a Defra spokesperson.

“This will help farmers to grow food in a more sustainable way and it will ensure public money is spent more efficiently and effectively.”

Campaigners warn that: “The Agriculture Bill, as currently drafted, is an empty vessel as it contains powers not duties and no budget," said Vicki Hird of the food system campaign group Sustain. "So unless it is amended, Michael Gove is really not obliged to deliver much - the opportunity to either encourage sustainable, high welfare farming or to discourage the most polluting, intensive forms of megafarms.”

Farm Subsidies explained

The European Common Agricultural Policy - or CAP - began in 1962 with guaranteed prices for farmers, the aim being to guarantee the security of Europe’s food supply.

In the 1970s and 1980s the policy resulted in overproduction, resulting in “milk lakes” and “butter mountains”. This led to an eventual shift from market support to direct subsidies for producers in the early 1990s, in an attempt to decouple support for farmers from the amount of food they produced.

The CAP has been controversial in the UK partly because the country receives much less from the budget than it contributes. The EU-wide mechanism for distributing subsidies also means large landowners get more money just for owning more land.

In September 2018, the environment secretary Michael Gove launched his proposed Agriculture Bill, setting out future support for UK farmers after Brexit. The bill sets out a seven year transition period from 2021, during which farmers will potentially be rewarded for public goods such as high environmental standards, ending direct payments after 2027.