Councils ignoring public right to audit accounts

Local authorities are refusing to let the public access key information on how their money is being spent, research by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has found.

Authorities are:

- redacting documents to “protect commercial interests”;

- setting up council-owned companies that are removed from scrutiny;

- failing to respond to members of the public who try to exercise their right to inspect council finances

The Local Audit and Accountability Act 2014 (LAAA) gives citizens and journalists the right to inspect the accounts and related documents of councils, police, fire and other local authorities, and to object to them if they believe something is amiss. It is an especially important right at a time when public bodies are under unprecedented financial pressure.

However, when Bureau journalists and volunteers attempted to exercise that right, some authorities withheld or heavily redacted the information. There was often little evidence that the public interest had been considered and no way of challenging the decision short of a costly court battle.

In one case, the Bureau was prevented from reading a contract because a council officer believed the company involved would sue. Another council refused access to the accounts of a company it had set up to manage a large property portfolio, raising concerns about transparency and accountability.

Duncan Hames, director of policy at Transparency International UK, said: “It’s critical that the public and press are allowed access to key documents about the finances of local authorities to ensure there is no place to hide for the misuse of public money.

“The law is clear that this financial information should be out in the open, so it is imperative that those failing to comply do not continue to withhold it from public scrutiny.”

Commercial interest over public interest

To test the law, Bureau Local volunteers submitted requests to nearly 50 local authorities asking to inspect documents — such as contracts and invoices — relating to the use of private consultants during multimillion-pound property deals, a subject the Bureau is investigating.

Some authorities gave only restricted access to the information, or refused altogether, often on grounds that releasing the information could cause financial damage to the councils and their business partners.

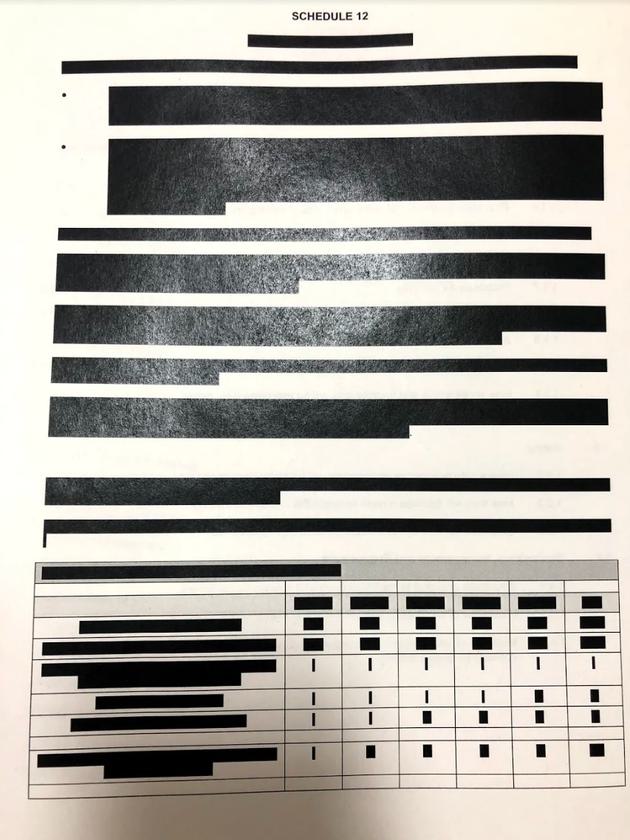

Haringey council provided a contract they had with property developers but it was heavily redacted. This is permitted if the information is considered commercially sensitive. When asked for the redactions to be reconsidered, the council insisted there was no remit to do so under the Act.

One of the redacted documents provided by Haringey council

One of the redacted documents provided by Haringey council

West Sussex county council, which has tens of millions of pounds in investment properties, completely refused to release copies of contracts relating to property consultants for fear of prejudicing commercial interests.

Other councils asked the companies in question for permission before deciding to provide — or not provide — copies of invoices and contracts.

A council in the north of England provided a large number of invoices but declined to supply contracts because, its finance director explained, one of the companies had a history of taking legal action against local authorities and the council could not afford to be sued.

New ways to spend money secretly

Some local authorities have set up companies to provide services and, in some cases, to oversee property acquisitions. The Bureau’s study suggests the growing use of these companies could impede transparency and accountability, because they do not seem to fall under the LAAA.

The Bureau submitted a request to inspect documents relating to property consultants used by Ashford council in Kent. In response, the authority said it did not own investment properties and so had not paid for any external advice. Instead it said that the properties in question, worth £27 million, were owned by A Better Choice for Property Ltd and that the company was not subject to the LAAA – even though it is entirely owned by the council.

The council later confirmed its company had used property consultants but would not disclose the fees because they were “commercially sensitive”.

Refusing to respond to citizens

Several local authorities — including Essex, Liverpool and Woking councils — simply ignored or failed to comply with requests to inspect their accounts.

PJ White, the volunteer in Essex said: “If councils are filling gaps in their budgets by investing millions in property acquisition, council-tax payers need to know the details. It is deeply worrying if a large authority like Essex thinks it can speculate without scrutiny.”

Many councils also had more rudimentary obstacles for the public to overcome. Councils are required to advertise that their accounts are open for inspection, but some posted these notices on obscure sections of their websites. Others did not include contact details. Some requests ended up in the hands of council staff with no knowledge of the LAAA.

Some of the issues might be explained by how few people are making use of the law. In 2015-16, the 11,000 eligible public bodies received 65 inspection requests. Several of the Bureau’s volunteers were told they were the first people to ask to inspect their authority’s accounts for decades.

Joseph Timan, a journalist who took part in the project, said: “I believe there is a general will to cooperate but the councils were simply unsure about what their exact obligations are.”

A glimpse at what the public can scrutinise

Despite the flaws with the legislation, some volunteers were able to obtain information on what councils are paying consultants to make multimillion-pound property investments.

Buckinghamshire county council provided a copy of a letter which showed it had contracted property consultants Carter Jonas to find and acquire investment opportunities on the authority’s behalf. The council later confirmed it had paid Carter Jonas £840,391 in relation to the purchase of investment properties, from 2017 to 2019.

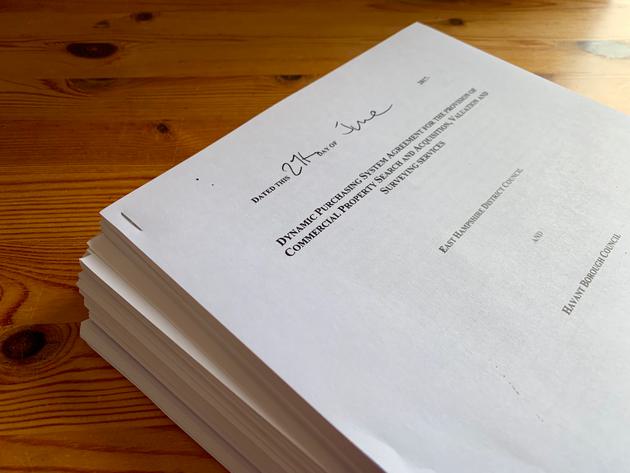

Other local authorities were more forthcoming - these are documents released for inspection by East Hampshire district council

Gareth Davies/TBIJ

Other local authorities were more forthcoming - these are documents released for inspection by East Hampshire district council

Gareth Davies/TBIJ

Other documents obtained show property consultants are actively pitching potential investment opportunities to councils, which the Bureau has found have effectively unlimited access to low interest finance from a government lending organisation.

Spelthorne borough council, which has borrowed £1 billion to spend on property investments, provided copies of contracts it has with the consultants Cushman and Wakefield. According to the documents, the company’s responsibilities included the “identification and procurement” of properties and “promoting Spelthorne borough council as the most credible buyer”.

Another invoice showed that the real estate agency Colliers International was paid almost £240,000 for its role in the £19.8 million purchase of a car park by Leeds city council in March this year. The decision to buy the car park was made under what is called “delegated authority”, meaning it was made by council officials behind closed doors.

In total Bureau Local volunteers obtained invoices or contracts relating to 22 property consultants used by 18 local authorities.

The volunteers also used the inspection powers to investigate other subjects. Reporter Tom Bristow successfully requested information from Norfolk county council about compensation payments paid out following the construction of a dual carriageway and blogger John Brace obtained documents which showed Merseyside Police had withdrawn cash totalling £76,461 during five trips to a branch of HSBC.

The government has announced an independent review into the transparency and quality of the financial information published by local authorities, which will focus specifically on the Local Audit and Accountability Act.

Why the Bureau Local is testing the LAAA

The transparency and accessibility of data concerning local authority finances has been a key focus of the Bureau’s investigation into the local government funding crisis over the past 18 months.

The Bureau Local discovered huge differences in the information released by councils and major errors in the data published by the government about their financial sustainability. These are significant obstacles for any member of the public trying to understand the decisions that affect their day-to-day life.

Bureau Local reporters used the Freedom of Information Act to fill some of these gaps, such as building a map of the community spaces sold off by local authorities, but that route also has challenges, with some councils failing to reply or exempting large amounts of information from their responses.

The Local Audit and Accountability Act offers another method of holding local government to account. The law, which coincided with the abolition of the Audit Commission in 2015, allows for inspections of local authority accounts and related documents during a set period each year.

The legislation also enables people to raise an official objection by asking their council’s external auditor to apply to the High Court for a declaration that an item within the accounts is unlawful, or to request that the auditor issues a report on whether certain spending was in the public interest.

Previously only eligible voters in the local area could use these powers, but in 2017 the right to inspect was extended to journalists, regardless of where they live. It was hoped the law, and its subsequent extension, would be a powerful tool for communities and media to scrutinise local authorities and the decisions they take.

The Bureau Local set out to test the law by working with volunteers to pursue council finance documents as part of our ongoing investigation.

The Bureau would like to thank the following people and organisations for contributing to this project: Adam Cantwell-Corn, Alastair Ball, Alex Seabrook, Andrew Nowell, Bryan Rylands, Chris Burn, Chris McKeon, Conor Matchett, Darryl Chamberlain, Fanny Malinen, Fleur Damen, Hazel Sheffield, Heather Brooke, Iraklis Taxiarchis, James Cracknell, Joanna Booth, Joel Lamy, John Brace, Joseph Timan, Josh Wright, Kenny Lomas, Mark Gale, Mina da Rui, Molly Williams, Neil Bellis, Paul Francis, Pauline Roche, People’s Audit, PJ White, Simon Lock, Tevye Markson, Tom Bristow.

Illustration by Hannah Eachus

Join the network

Become part of the Bureau Local — our collaborative network of reporters and citizens — and tell stories that matter.

Find out moreOur reporting on local power is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.