The baby brands turning Indonesian Instagram into free formula ads

Multinational baby formula companies, such as Nestlé and Danone, are using social media to market to consumers in South East Asia in ways that raise serious concerns they may violate World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. The companies have changed their advertising tactics during the coronavirus outbreak and are also using mothers to create online marketing material, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism can reveal.

Recent activities have included themed webinars and Q&A sessions with experts. And, in the past few years, both Nestlé and Danone have begun to leverage the popularity of social media to in effect turn Indonesian consumers into unpaid and underregulated advertisers.

WHO introduced an international ethical code for formula marketing in 1981, after Nestlé’s advertising practices in developing countries attracted international attention and made it subject to a boycott campaign. A 2016 resolution clarified that “growing-up milks” for children under the age of 36 months fall under its scope.

While there is no suggestion that either company has broken any laws, public health experts have expressed concerns that their actions go against the spirit of the WHO code. Health experts say that aggressive advertising undermines breastfeeding efforts and can cause mothers to move to formula unnecessarily. WHO recommends that, where possible, babies are exclusively breastfed for the first six months and receive continued breastfeeding up to the age of two and beyond.

What is the WHO international code?

Adopted in 1981, the WHO code is a set of recommendations to stop aggressive and inappropriate marketing of formula, bottles and teats.

The code advocates that babies be breastfed. Breast-milk substitutes (BMS) should be available when needed, but not promoted.

It covers BMS products including infant formula, follow-on milk and toddler milk for children under the age of three.

Among other provisions, it states that:

- There should be no advertising or other form of promotion of BMS to the general public.

- BMS manufacturers and distributors should not provide samples of their products to pregnant women, mothers or members of their families.

- Companies should not seek direct or indirect contact with, or provide advice to, pregnant women or mothers.

Source: World Health Organization

“[Companies] promote freely,” said Nia Umar, head of the Indonesian breastfeeding mothers association. She believes it’s violating the code, “but it’s not against the law. They know the gap. And since the gap is very big and very wide, they use it to promote unethically.”

Nestlé said: “The WHO code and subsequent WHA (World Health Assembly) resolutions are recommendations for member states to translate into local legislation... This is why we apply WHO recommendations as implemented in law by member states.” (Emphasis theirs.)

Mum’s the word

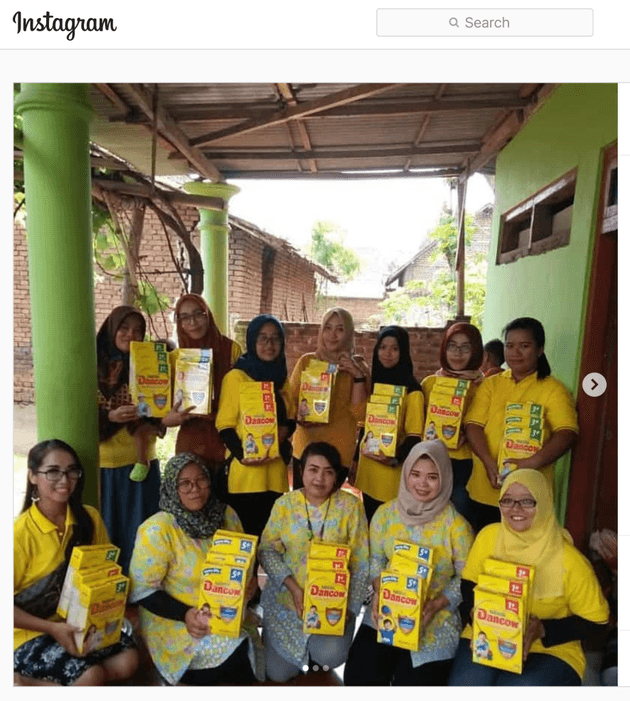

In 2014, Danone’s Indonesian formula brand SGM launched its “mombassador” scheme. Each year, women aged between 21 and 35 are encouraged to become brand ambassadors. Judged in part on their social media presence, successful applicants are invited on a three-day trip to visit a Danone formula factory and attend a gala dinner.

On their return, mombassadors are encouraged to host parenting events, some at government-run health centres, and publish posts promoting SGM online. Women who have taken part in the programme told the Bureau that they were offered regular training, including classes on nutrition and child development, shooting and editing photos, writing social media content and recording vlogs.

Danone claims to have more than 400 mombassadors across Indonesia. The company does not cover the cost of transportation to participants’ classes and does not pay the mothers directly for their branded social media posts.

“I am only a middle-school graduate,” said one mother. “The most important thing is knowledge, right? For me, paying for transportation [to classes] is not really a big deal. Going to school, you have to pay tuition. The [mombassador] programme is free and useful.”

“It's not that these are bad women doing this,” said David Clark, a nutrition specialist at Unicef. “They're being manipulated.” He believes the programme breached the WHO code. “There is no doubt in my mind that mommy bloggers and brand ambassadors are involved in a form of promotion that is prohibited by the code."

The WHO code prohibits formula marketing to the public, but its guidelines are not legally binding. While 70 per cent of WHO member states have enacted some legal measures against formula marketing, only 25 countries have adopted legislation that substantially aligns with the code. Indonesia’s laws are “moderately aligned with the code”, according to WHO.

In its most recent report on formula marketing, released in May, WHO noted that social media advertising was a “cause of growing concern”.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has provided multinationals with new marketing opportunities. Nestlé's Indonesian formula brand Dancow ran ads featuring straplines such as “Bunda, Lindungi Si Buah Hati” (“Mother, protect your sweetheart!”) next to images of children drinking formula. The company has also used its hashtag #DancowLindungi (#DancowProtects) frequently on its posts since March 2020.

The code bars companies from seeking direct or indirect contact with pregnant women and mothers but during the pandemic Dancow has hosted webinars discussing infant nutrition and live-streamed an event, called “ParentFest”, featuring pediatricians and social media influencers. The event, which took place during Indonesia’s national lockdown, was billed as an online festival to support mothers “learning from home”. Dancow products were prominently placed in the host’s video feed.

Danone’s SGM brand has done something similar during lockdown, encouraging consumers to post questions to child psychologists and nutrition specialists who gave talks on the brand’s Instagram and WhatsApp platforms. Contrary to the code, Danone advertised its customer careline on Facebook and urged mothers to call if they had questions about their child’s growth and development.

The WHO also states that companies should not market any formula product for children under the age of three. But Nestlé’s recent Facebook ads in Indonesia show products for children aged one and above. Nestlé said that all of its communications comply with Indonesian law, “where advertisement of products for children above one year old is allowed”.

Last year, Danone introduced a points system for its mombassadors. Mothers receive briefings from the company that describe what to include in their content and are asked to post on social media three times per week. Each post is worth a certain number of points, women said, with blog entries commanding more than Facebook or Instagram content. Those with the most points each month are given shopping vouchers, worth up to IDR600,000 (about £32). Those with the highest total at the end of the year receive a holiday in Bali.

“Since they started the achievement point programme, I’ve seen many [mombassadors] starting to be active again,” one mother said. “After all, this also helps us. Especially during the pandemic. With IDR300,000 we can buy children's milk and other necessities.”

Receiving points, however, is dependent on strict stipulations. Posts, which must be approved by programme leaders, have to include brand-related hashtags and colours, and tag three friends who are not mombassadors. One mother told us how she lost out on 250 points by misspelling a link to the SGM website.

Our work to expose and report on issues like this drives positive change. You can help us do more

Please support the Bureau today.Danone said that the initiative was purely informational and did not promote any baby formula products. It also said that the company “ensured that all participants in the mombassador programme are in compliance with the principles as set out in the WHO code, Danone’s BMS [breast-milk substitute] policy and relevant local regulations”. Women in the programme spoken to by the Bureau indicated they could not recall being told about the WHO marketing code.

Nestlé had a similar scheme. The Dancow Inspiring Mom campaign, which last ran in 2018, included a three-day trip to Jakarta, a visit to Nestlé’s factory and classes on parenting and nutrition. Additional classes on “make-up and grooming”, financial management and social media were also provided. The women were then expected to “share information” and “inspire” their local community while promoting the brand.

“I think that it is fair to say that [a] company is violating the code in encouraging people to promote, even using their own words,” Laurence Grummer-Strawn, a specialist in infant nutrition at the WHO, said. “We’re very concerned that it does influence people’s decisions and is promotional in that sense.”

A 2016 study published in The Lancet stated that increasing breastfeeding to near-universal levels could prevent the deaths of more than 820,000 under-fives every year. An editorial in the same year called for a complete ban on social media advertising of breast-milk substitutes, stating: “From tobacco, to sugar to formula milk, the most vulnerable suffer when commercial interests collide with public health.”

Both companies told the Bureau that they take any allegation of non-compliance seriously and have robust systems to encourage people to report any concerns around marketing practices.

Broadening horizons

Rapid urbanisation and more women in the workplace have attracted industry giants such as Nestlé and Danone to South East Asia, where sales have boomed. Last year, the region’s formula industry was valued at $6.5bn, according to Euromonitor International. Nestlé invested $100m in its Indonesian factories alone.

The formula industry’s efforts are set against a backdrop of worrying trends in breastfeeding. In a national health survey published in 2012, the Indonesian government noted that “the introduction of infant formula takes place for many children much earlier than the recommended age of six months”.

In 2017, Indonesian national data showed that just 38 per cent of mothers exclusively breastfed their baby from birth to six months. The percentage of children under six months who were never breastfed increased from 8 per cent to 12 per cent in the five years up to 2017. A 2016 study in Java found that more than 70 per cent of pregnant women and new mothers had seen promotional materials for breast-milk substitutes. Women who recall such marketing are more likely to use formula than those who do not.

In February, the executive board of the World Health Assembly discussed the growing threat of online formula advertising. It highlighted tactics such as industry-sponsored online social groups, targeted Facebook advertisements and blogs, and put forward a request for WHO to work further on the issue.

The request has yet to be formalised due to the coronavirus pandemic. But even without an official go-ahead, experts recognise the need for more forceful legislation by national governments.

“There doesn't have to be a change to the code for countries to implement laws,” Grummer-Strawn said. “Countries can step up when they see these behaviours and say, well, we need to make sure that our law covers that.”

Some experts predict that, without adequate legislation and enforcement, formula companies will continue to flout WHO guidelines. “They’re in this business to make money and to sell products,” David Clark said. “But we have to have a regulatory framework in place that stops them exploiting and manipulating the public.”

Additional reporting and translation by Esti Wahyuni.

Header image: A child having formula milk. Credit: Giacomo Pirozzi/AIMI