Cameron exploited lobbying loophole to discuss $1bn China fund with Treasury

David Cameron discussed the establishment of a $1bn UK-China investment fund – of which he was to become vice-chair – in a meeting with then chancellor Philip Hammond just 15 months after leaving office as prime minister, despite the convention aimed at preventing former ministers from lobbying for two years.

Correspondence obtained by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism indicates that the meeting drew no concerns from the ministerial jobs watchdog because Cameron had not yet begun a formal role with the fund, highlighting yet another loophole in the UK’s lax lobbying guidelines.

As part of its transparency obligations the Treasury had previously disclosed that Cameron met Hammond, who served as his foreign secretary, in October 2017 “to discuss China”. It had not said whether their discussion included the $1bn UK-China fund that Cameron was in the process of helping establish.

The Bureau can now reveal that Cameron told Hammond “of his plans to create a commercial UK-China fund to invest in innovative, sustainable and consumption-driven growth opportunities”. This was admitted by Hammond to Peter Dowd, Labour MP for Bootle and then shadow chief secretary to the Treasury, in an April 2018 letter that has not been reported on until now. It also reveals that Cameron received general government approval for the proposed venture.

A spokesperson for Cameron told the Bureau: “In 2017 he held meetings with both UK and Chinese ministers about the potential for a fund, to ensure that if a fund was established, it would be welcomed by both governments.”

This revelation adds to the mounting concern over the former prime minister’s lobbying activities and has left the government facing increased pressure to release full details of the meetings in question.

While it is unclear whether Cameron made any requests of Hammond (and the latter said his former boss informed him about the investment fund “in the interests of transparency”), the then chancellor publicly endorsed the fund shortly afterwards during a trip to Beijing.

The timing of the meeting is also noteworthy for two reasons: it was two months before Cameron received approval from the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (Acoba) to take up a formal role with the fund, and it was well before the end of the two-year lobbying ban that kicked in when he left office.

Corruption, wrongdoing and systemic failings. We expose it.

Sign up here and be the first to find outIt is another example of Cameron seeking to use his access to the top levels of government to promote personal business interests with which he has become involved since leaving office. He is already facing seven different inquiries in connection with his lobbying for the collapsed finance company Greensill Capital.

Rather than simply provide strategic advice to his business partners, Cameron has in some instances taken an active role in lobbying efforts, directly contacting ministers and other government officials with requests. The new details also underline the ineffectiveness of the current system for regulating former politicians’ business activities.

Cameron’s activities highlight what anti-corruption campaigners describe as the potentially corrosive effects of lobbying – be it for ordinary companies or more controversial businesspeople and foreign governments – on British politics, an issue the Bureau is examining through its Enablers project.

Like Cameron’s fund, Greensill was reportedly planning to invest in China as part of its global expansion. While Greensill has collapsed, the Bureau understands that, more than three years after its inception, Cameron’s fund has yet to be formally established. After his lobbying efforts on behalf of Greensill were exposed, Cameron said it “was right” for him to make those approaches. In a statement on 11 April, he listed what he said was all the work he had been involved in since leaving office. However, he did not mention his China fund.

Government green light

At the October 2017 meeting, Hammond expressed his general support for Cameron’s project.

“As I noted to Mr Cameron during our meeting, the government is generally supportive of any private sector initiative that furthers UK-China collaboration,” Hammond said. “Mr Cameron did not at that stage have specific plans for his role in the fund, nor did he ask for government support, given the government has no involvement in the staffing of private sector initiatives.”

This was seemingly contradicted by Acoba, which told the Bureau that Cameron applied for advice from the committee the same month and, according to Acoba’s advice letter in response, “explained that he would be vice-chairman of the fund and this would be a paid role”.

Within two months, Acoba had approved Cameron’s role. It outlined a broad remit for him, including an active role in the fund’s strategy, structure and investments.

The chair of Acoba was Baroness Angela Browning, whom Cameron put forward for a life peerage in 2010 and who had acted as a junior Home Office minister in the House of Lords under his premiership. There is no suggestion she has acted inappropriately.

When Dowd asked Acoba to explain the matter, Browning responded by saying Cameron’s meeting with Hammond took place before the body issued its advice and imposed conditions on him taking up the role, including his continued compliance with the two-year lobbying ban.

She said she hoped Dowd could “be assured that Mr Cameron made the committee aware of general discussions [that] had taken place with government in advance of the committee’s advice and the establishment of the fund”, according to an April 2018 letter from Browning to Dowd seen by the Bureau. Browning left her position as Acoba chair last year.

Browning told the Bureau: “I expect all rules and advice to be adhered to. In my letter to the prime minister at the front of the 2017/18 annual report I expressed concern about the lack of statutory powers and enforcement.”

Acoba said: “The independent committee’s role is to give advice under the government’s rules and make that advice transparent. All other matters – such as whether the rules are right or whether ministers are able to meet former prime ministers – are a matter for the government.”

While the ministerial code says that departing ministers and senior civil servants must seek advice from Acoba when taking on a private sector role, the body does not have any power to enforce its recommendations.

Lord Bob Kerslake, former head of the civil service and a crossbench peer, said the weakness of the process has been exposed by the current scandal around Cameron’s lobbying, as well as the decision by former chancellor George Osborne to take the position of editor of the Evening Standard before receiving Acoba clearance.

Kerslake is concerned that the current system allows for legal work-arounds to circumvent the intended safeguards. “It relies on people playing by the rules, and there are some high-profile cases where people have not followed the process,” he told the Bureau. “That, I think, has weakened it to the point where we need to look again at whether a statutory model is needed. I think there’s a strong case for it.”

Responding to the latest news, Jill Rutter, a former senior civil servant, called on the government to publicly clarify whether Cameron failed to comply with any guidelines. Rutter told the Bureau: “The Treasury should release the minutes of the meeting as soon as possible and also needs to let us know whether there was a civil servant present in the meeting or if this is just Philip Hammond reporting afterwards. That's the only way of knowing what David Cameron has said [to] him in a private discussion.”

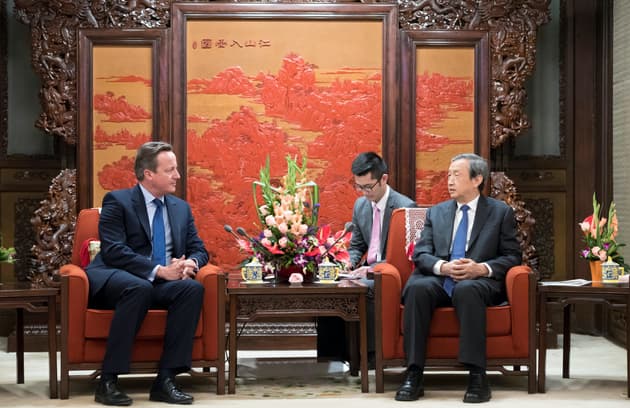

David Cameron meets Chinese vice premier Ma Kai on his Beijing visit in September 2017

Ding Haitao/Xinhua/Alamy

David Cameron meets Chinese vice premier Ma Kai on his Beijing visit in September 2017

Ding Haitao/Xinhua/Alamy

Philip Hammond with Kai during the then chancellor's visit to China, two months later

Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty

Philip Hammond with Kai during the then chancellor's visit to China, two months later

Fred Dufour/AFP via Getty

‘Something is rotten’

During a visit to Beijing in December 2017, Hammond and Ma Kai, the Chinese vice premier, publicly endorsed Cameron’s fund as a way to “create employment and boost trade links”. Cameron had already discussed the fund with Ma when he visited three months earlier.

Cameron’s pursuit of the China fund – which he said would be based in Ireland – is a reminder of the close alliance he sought with the country while in office, a stark contrast to the deterioration in relations that has occurred more recently over China’s treatment of Hong Kong and of the Muslim Uyghur minority in its Xinjiang province.

During his 2017 visit, Cameron tweeted that he was in Beijing “to reinforce [the] UK’s close relationship with China and the ‘golden era’ – something I’m very proud of”.

The fund, which Cameron set up with the veteran public relations executive Peter Gummer, who is a member of the House of Lords, was focused on investments in technology, healthcare, high-end manufacturing, infrastructure and new energy.

Dowd told the Bureau: “Something is rotten when a former prime minister can directly lobby the chancellor just over a year after leaving office to endorse a new business proposal.”

“This meeting and the endorsement of the role is then signed off by a regulator he appointed, on the basis that he hadn’t yet formally started in the role.” In Dowd’s view, “it appears the former prime minister’s status and personal relationships have allowed him ministerial contact without having to go through adequate motions of transparency”.

A spokesman for the former prime minister said: “David Cameron has never lobbied the UK government about the UK-China fund and no work or tentative discussions about the fund took place while he was prime minister. These discussions [in 2017] were not in any way seeking financial support for the fund, but merely to gain support for the concept of a bilateral fund.”

The Treasury said: “The bilateral UK-China investment fund was a private, commercial venture. Like other private initiatives mentioned at the dialogue it did not involve government participation or funding.”

Cameron and China

As prime minister, David Cameron championed closer ties with China, something he described as the “golden era” of relations with the world’s second-largest economy. His approach largely rested on the belief that as China develops, it will also become more democratic.

That vision drove Cameron to establish his UK-China investment fund, which would invest in technology, renewable energy and healthcare projects. It was a way of benefitting from what he saw as the world’s biggest economic growth story.

Cameron couldn’t have been more wrong. President Xi Jinping has changed the constitution so he can remain leader for life. The Chinese government has brutally cracked down on opposition protests in Hong Kong and introduced laws eroding its citizens’ civil rights.

Several countries, including the US government and British MPs, are now describing China’s treatment of the Uyghur minority in its western Xinjiang province as a genocide. Last year, prime minister Boris Johnson decided to cut China’s Huawei out of Britain’s 5G telecommunications infrastructure over concerns that it was too close to its government.

As relations between China and the West deteriorate, any investments Cameron makes are certain to attract intense scrutiny. On the other hand, more than three years after starting the fund, he has yet to announce a single project.

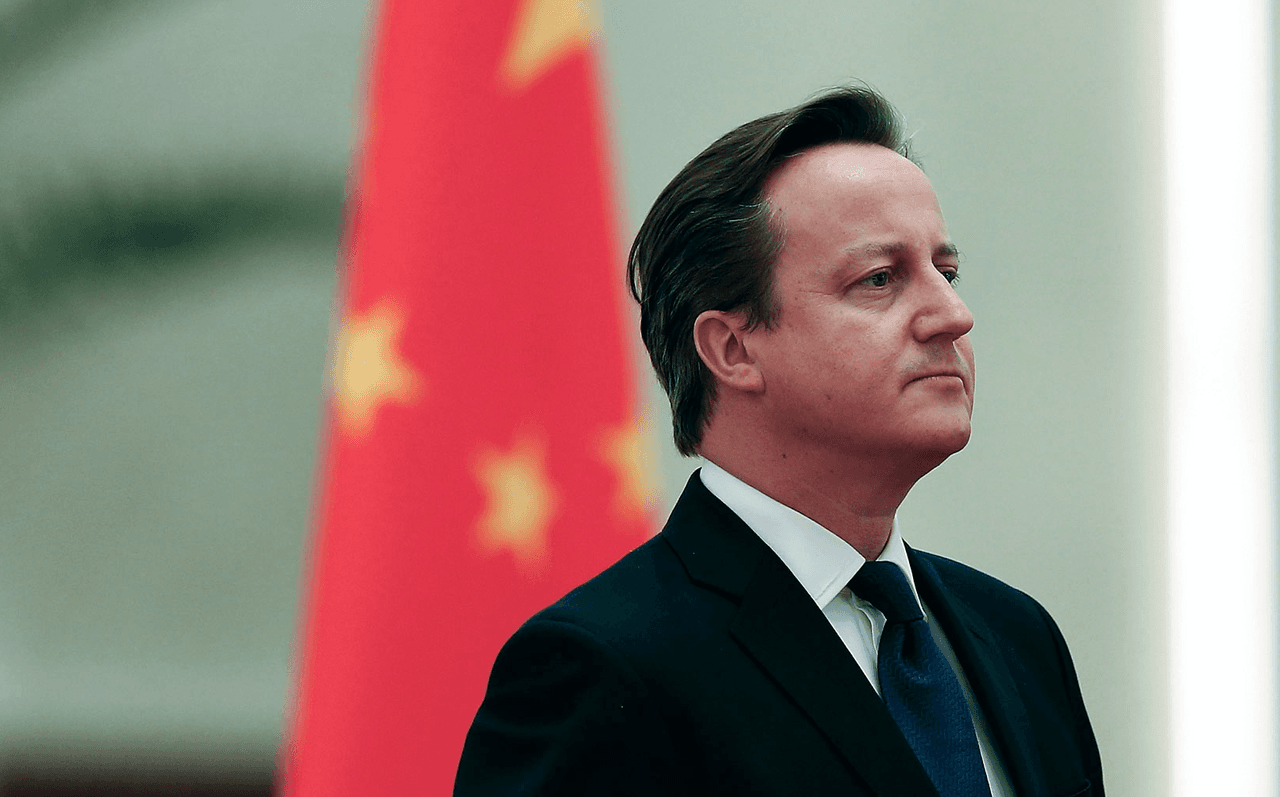

Header image: David Cameron during a visit to Beijing in 2013. Credit: Lintao Zhang/Getty

Reporters: James Ball and Franz Wild

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: