The bean destroying the planet: can the soya trade be cleaned up?

Soya is the hidden ingredient on our dinner plates. For farmers, it is a magic bean that helps pack muscle onto chickens, pigs and cattle. But there are mounting concerns about the expansion of soya farming around the world, especially in Brazil, and the impact this is having on the natural environment.

Why is soya used as animal feed?

Soy or soya, originally native to Southeast Asia, is prized as the most important protein source in farmed animal feed. Dairy farmers say soya feed helps produce protein-rich milk. Globally, it is estimated that roughly 80% of all soya produced is fed to livestock, including poultry, beef and dairy cattle. In the UK, which imported about 3.5 million tonnes of soybeans in 2019, the figure is somewhere between 75%and 90%.

Although many countries now grow soy, the global trade is overwhelmingly supplied by just three nations: Brazil, Argentina and the US. The UK sources at least 27% of its soya from Brazil and at least 42% from Argentina, according to industry estimates.

What’s the problem with soya?

In Brazil and Argentina, soya cultivation is associated with damaging social and environmental impacts, including high levels of deforestation.

A ban on clearing the Amazon rainforest for soya production, known as the soya moratorium, was agreed in 2006. This is credited with reducing deforestation in the area, but the problem persists, and it has moved elsewhere, notably to the Cerrado biome, an important Brazilian ecosystem. Global exports of Brazilian soya were still linked to 500 sq km of deforestation in 2018, according to the supply chain consultancy Trase.

Awareness of the problem has grown rapidly in recent years, with food companies and livestock industries scrambling to address the issue. But their supply chains are often complex and opaque.

Is ‘certified’ soya the answer?

Because of the complexities of global soya supply chains, many food manufacturers, fast food chains and supermarkets now rely on certification schemes that promise to offset or cancel out their environmental damage.

For example, in the UK, chicken restaurant chain Nando’s and the supermarket Asda have used “credits”, the most basic certification tier that involves buying offsets for every tonne used. Among the most well-known credit schemes is one run by the Round Table on Responsible Soy Association.

The money invested supports farmers producing sustainably, but the actual soya in the supply chain is not necessarily deforestation-free. McDonald’s has said it uses credits, among other schemes. Some dairy manufacturers, including those highlighted in our investigation – Arla Foods and Saputo – also say they use the credit system.

The next tier up in the certification rankings, used by the supermarket Tesco, is known as mass balance. This means certified, sustainable products must be in the supply chain, but the supplier may mix this in with beans from deforested farms. Under mass balance, Tesco and its meat suppliers would only purchase a volume of the crop that matched the original amount of sustainable soya.

Cargill’s controversial Triple S certification scheme, which has several major UK customers, including a feed company and Asda, is one type of mass balance scheme. Triple S is operational in Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. In Brazil, Triple S farms operate in the states of Goiás, Mato Grosso, Mato Grosso do Sul and Pará.

The scheme rules out soya from land deforested after 2008, and from land protected by governments or international ecosystem protection agreements.

Critics, such as Greenpeace UK, say such credit schemes are not good enough, with no guarantees that soya is deforestation-free, effectively allowing it to continue. Companies using certification say they help fund progress towards less destructive farming, but almost all admit more needs to be done – albeit in five or 10 years.

“Segregated” soya is at the top end of the certification rankings. This system guarantees that the supply of raw materials, from farm to customer, keeps specific consignments of sustainably produced soya separate from other crops. One global grain trader, ADM, now offers this option, and at least one retailer has said it plans to use such systems. But one multinational feed company, For Farmers, has said the cost of moving towards the top end of certification is prohibitive.

What about alternatives?

A recent study shows many other protein sources, including rapeseed meal, distillers’ grains and pulse grains such as beans and peas, are suitable for livestock feed. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization has also found that insects could replace between 25% and 100% of the soya used for livestock, depending on the kind of animal. Some farmers themselves are experimenting with reduced or no soy feed regimes too.

However, the cost, availability of alternatives and sheer volumes of feed needed are all barriers to a speedy wholesale switch, farmers and industry figures say. However, one feed company is now offering a “soya free” range, using homegrown ingredients such as rapeseed.

What do dairy farmers think?

The Bureau spoke with several farmers, some supplying milk to Saputo and Arla, and found mixed views and awareness around the use of soy. One said they had never considered the link between the feed and deforestation, the priorities being “cost, the welfare of cows and good quality, protein-rich milk”.

Another said they had “stopped using soy feed a year ago” and were using alternatives. They said that they “expect soy will be banned, and the pressure will come from retailers and big processors, but without much consideration for farmers being able to access suitable alternatives at volume”.

One, who farms organic cattle and non-organic goats, said he uses no soya for his organic herd and that most of his feed is homegrown – but does use soya for goats. He said he always checks the country of origin “and buys North American soya to avoid links to deforestation”.

Reporters: Andrew Wasley, Alice Ross and Anna Turns

Environment editor: Jeevan Vasagar

Investigations editor: Meirion Jones

Production editors: Alex Hess and Emily Goddard

Impact producer: Grace Murray

Fact checker: Alice Milliken

Legal team: Stephen Shotnes (Simons Muirhead Burton)

Our Food and Farming project is partly funded by Quadrature Climate Foundation and partly by the Hollick Family Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over our editorial decisions or output.

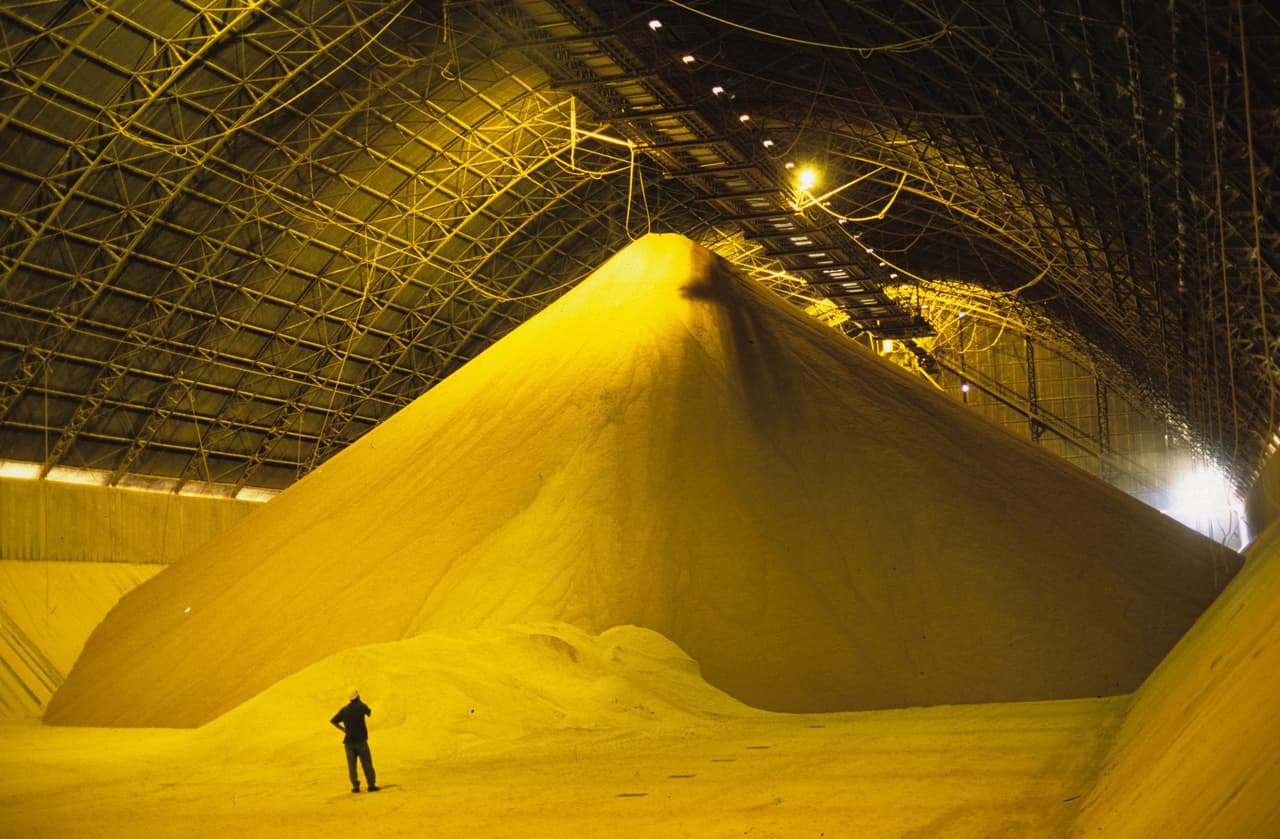

Header image: Soy beans growing in Brazil. Credit: Victor Moriyama/Greenpeace

-

Area:

-

Subject: