Sent to jail for feeding the pigeons: the broken system of antisocial behaviour laws

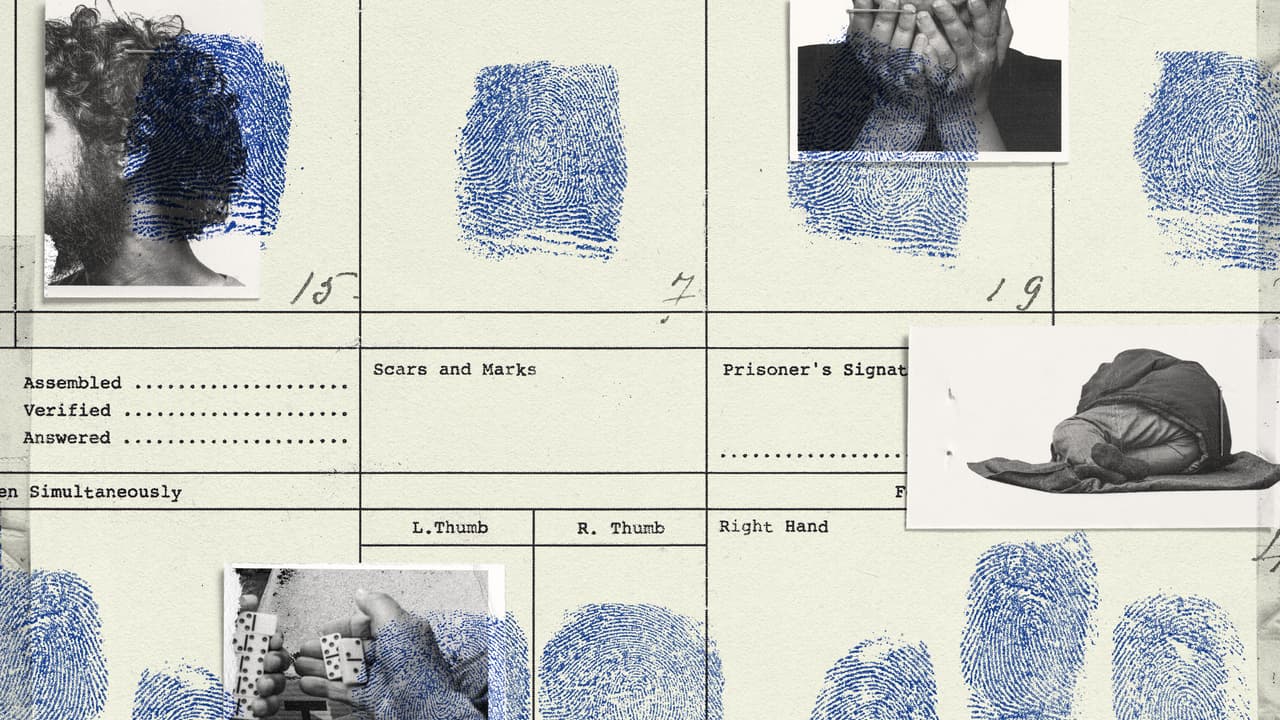

Mentally ill people are being sent to prison in England and Wales for breaking antisocial behaviour rules that experts say they are unable to follow. They often face their court hearings with no legal representation and can be sent to prison even if their actions are deemed to have caused no real harm.

People sentenced to prison under these rules in the last three years included a homeless man who was given six months in jail for breaching an injunction that ordered him to stop begging and another man sentenced to 15 weeks for failing to stop feeding pigeons from his balcony. In one instance a woman was moved directly from a mental health hospital to a six-month prison stretch.

“Antisocial behaviour” is a broad legal term that covers actions ranging from harassment or threats to playing loud music, drinking in the street or even sleeping rough.

In England and Wales, this used to be dealt with via the antisocial behaviour order (ASBO) but a 2014 legislation introduced a new way to tackle the issue: a civil injunction, which sets out a list of things the recipient cannot do or actions they must take. If the person breaks these rules, they are considered in contempt of court – which can be punished with prison.

The Bureau has found this system to be riddled with severe problems. Injunctions have been handed out against people begging on the streets, elderly men playing dominoes in public and numerous people with debilitating mental health issues. Police even applied for an injunction to stop a suicidal woman from standing on a bridge, meaning an attempt to kill herself would have been contempt of court and could have ended in her imprisonment.

The Ministry of Justice does not collect any data on when and how antisocial behaviour injunctions are used or what happens when they are breached, so the Bureau analysed hundreds of court judgments, published between 2019 and mid-2022, to create a first-of-its-kind database. We found:

At least every eight days someone is in court facing prison for breaching an antisocial behaviour injunction.

Women make up 27% of people jailed for antisocial behaviour – a proportion seven times higher than women in the wider prison population.

At some hearings, judges openly expressed concern that the person’s actions had caused no real harm but, given the limited sentencing options for contempt of court, sent them to jail anyway.

Several lawyers told the Bureau that the majority of the people they had seen given injunctions did not have the mental capacity to face court, let alone adhere to the rules of the injunction.

The Bureau spoke to people with serious mental health issues who had been given injunctions, one saying “I don’t think I’ll ever get over it” and another describing the process as “a nightmare” that had “ruined our lives”.

A passage to prison

Few cases exemplify the pipeline from mental health problems to prison as starkly as Charlotte’s. Charlotte spent her childhood in care and was repeatedly sexually assaulted in children’s homes. As an adult, she has a history of serious mental health issues, including overdosing and self-harm.

In 2020, her social housing provider brought an injunction against her, which she subsequently breached by shouting at neighbours and housing officers, refusing officers entry into her house and by failing to attend mental health treatment. She was brought before a court, where a judge requested a mental health assessment as a result of her “shouting and interrupting the proceedings”– and she was remanded to prison.

In prison awaiting her hearing for breaching the injunction, Charlotte’s mental health worsened and she was sectioned in a mental health hospital. When her hearing did take place, the judge noted her history of serious mental health issues – but nonetheless gave her an immediate prison sentence of six months. To compound Charlotte’s trauma, her housing provider was pursuing a possession order. She would almost certainly be homeless when she was released.

Charlotte is one of a markedly high number of women who have found themselves in prison for breaching these injunctions. We found that women made up 27% of those sent to jail in such cases; in the prison system overall, this number is just 4%.

Prison sentences could mean women losing their homes and even custody of their children. Nicola Drinkwater, head of campaigns and public affairs at the charity Women in Prison said: “Prison is a dead end, one that tears families and communities apart. And the government’s own strategy acknowledges that most women in prison should not be there,” she said. “It doesn’t have to be like this.

The Bureau also found scores of people sent to prison each year on short sentences for relatively minor issues. In some cases they were up in court facing prison just a week after being given the initial injunction. In one instance, a man imprisoned for breaching an injunction ordering him to stop begging in public was sent back to prison just days after his first stretch ended for breaching the same injunction.

Our analysis also revealed the average sentence was just 86 days. Some were as little as two weeks. In many instances people were sent to prison in the height of the pandemic, when Covid was known to be raging through prisons and people were locked in cells for 22.5 hours a day on average. Some of those facing prison for breaching their injunction caught Covid while being held on remand.

Andrea Albutt, the president of the Prison Governors Association, told the Bureau that such sentences are pointless. “Invariably the reason why the person has the antisocial behaviour injunction is because of their mental health,” she said, “and if they come [to prison] for short periods of time, we don’t have them long enough to stabilise them [and] their antisocial behaviour becomes worse.

“They can become very psychotic when they come into prison and we do not have the facilities to manage them. Putting people in prison for short periods of time for a civil offence is just crazy.”

Facing jail – without a lawyer

When Diana was given an antisocial behaviour injunction after falling out with her neighbours, she struggled to find a lawyer who worked on legal aid. Many do: 41% of people in England and Wales are without a housing legal aid provider in their local authority. It meant that when her injunction was first handed down, Diana, who is 75 and has struggled with her mental health for years, had no one to fight her case in court.

Diana remembers what it felt like to be in court alone, representing herself: “I couldn’t speak. I lost my voice when they were talking to me because of the nerves.”

Her injunction laid out how she could be arrested if she broke any of its stipulations. “I said to people, ‘I could go to prison ... I could get a prison sentence and my home and my dog would be gone, you know, my life would be over,’” she said.

Diana later found a lawyer who asked a psychiatrist to assess her. The psychiatrist noted she had severe depression, paranoid delusions, problems with her short-term memory and major impulse control issues. He said her mental health conditions were the cause of her antisocial behaviour and meant “she will not be able to comply with the conditions of the injunction at all times”. Yet the injunction was upheld.

As predicted, she breached the injunction several times, and was taken into police custody on more than one occasion as a result. In one instance, she smeared food over the cells walls and picked paint off the cell door – for which she was then charged with criminal damage and fined.

Diana has since been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and is now on medication. And she has moved house, away from the neighbours she fell out with. But the memory of the injunction stays with her. “I don’t think I’ll ever get over it,” she said. “I’ve never experienced such a horrific thing in my life.”

In Diana’s case, the injunction did not lead to prison – but for many people like her it does. The Bureau found 11 instances in which a person’s mental health issues were explicitly mentioned by the judge who handed down a custodial sentence. People in court facing prison sentences included those with personality disorders, debilitating OCD and schizophrenia.

“We see desperately ill people produced to court,” said Rosaleen Kilbane, a partner at the Community Law Partnership. “The big flaw of the system is it presumes people committing antisocial behaviour are doing so deliberately and will respond to the injunction. It is not at all uncommon for people to go to prison.”

Shifting the responsibility

When the new civil injunctions were created in 2014, they were designed to tackle disruptive behaviour both in domestic settings and in public. Applications for an injunction could be made by a range of people and official bodies, including police, council officers, housing providers and British Transport Police.

Yet the Bureau found that 97% of judgments for injunction breaches since 2019 were brought by social housing providers or councils (where the complainant was known). The charity ASB Help recently ran a training for 400 police officers about antisocial behaviour and were surprised to hear most officers had never considered using injunctions.

A government spokesperson told the Bureau: “We are committed to tackling and preventing antisocial behaviour, which has a devastating impact on victims and communities.

“The Antisocial Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 provides the police, local authorities and other agencies with flexible powers they can use to protect communities and prevent harm. It is for local areas to determine how best to deploy these powers, however, we expect them to be used proportionately.”

Yet some lawyers say that the new injunctions have essentially served to shift the responsibility for dealing with low-level criminality on to housing associations. “They are now taking on the mantle of community police force,” said lawyer Ben Taylor. “It doesn’t work.”

Nor do landlords necessarily prioritise their tenants' welfare when considering an injunction application. During the pandemic, when a pause on possession hearings prevented landlords from evicting tenants, lawyers at Doughty Street Chambers said they had noticed an increase in applications for antisocial behaviour injunctions. This was because an injunction meant that the case would be prioritised when the courts reopened – and an injunction breach would mean the judge had no choice but to allow the eviction.

Social landlords could therefore use antisocial behaviour injunctions as a means of fast-tracking an eviction – but with the unintended side-effect of the evicted tenant possibly being sent to prison. Since the first lockdown, social housing providers and councils have brought 93 injunction breaches to court, of which 41 ended in the person being sent straight to prison.

The Bureau also found social housing providers using injunctions against behaviour that would not usually be considered antisocial.

This was the case for Sarah, a severely disabled woman who was given an injunction after she refused to let her social landlord into the property she part-owned in order to fix a leaking pipe. In court, the judge said that the use of an injunction in this instance “causes me to raise my eyebrows”. The case was dismissed months later, but not before Sarah had faced two court hearings without legal representation. She told the Bureau that she was facing “unfair and untrue set of accusations made against me by my housing association”.

The current system is weighted against the recipient of the injunction on various levels. Social housing providers, councils or police can apply to the courts without the person in question being told or given the opportunity to defend themselves. Rather than requiring a criminal level of proof, the judge needs only to be convinced on a balance of probabilities. And while there is supposedly a duty on the applicant to present both sides of the situation fairly, this does not always happen.

Stephen had lived in his home for more than 20 years when he became embroiled in an intense dispute with two of his neighbours. He remembers finding out about his injunction when a man knocked on his door one evening with a letter in his hand. “I went inside and read it – and I was absolutely gobsmacked,” he said. “I didn’t see it coming.”

The injunction said that he was not allowed to swear, shout, threaten violence or cause any nuisance to his neighbours. At the top of the letter was written: “IF YOU DO NOT OBEY THIS ORDER YOU WILL BE GUILTY OF CONTEMPT OF COURT AND YOU MAY BE SENT TO PRISON, FINED OR YOUR ASSETS MAY BE SEIZED.”

The dispute had been hostile. Both he and his neighbours had complained about each other to the housing association and the police, and both Stephen and his neighbours were being investigated by the police.

But the housing provider decided to apply for an injunction against Stephen only, triggering a court process that he had no idea was even taking place. With Stephen absent from court, it went unmentioned that the dispute and threats had been going both ways. The housing provider also failed to mention that Stephen’s doctor had written to them warning that he had “a diagnosis of major depressive disorder” and that the altercations with his neighbours had worsened his condition and left him “struggling with a persistent sense of threat”.

Stephen found a lawyer to help him challenge the injunction and in court a judge noted that those making decisions on whether to grant an injunction have very little time to rule on applications, which are often “squeezed in amongst a number of other pre-listed matters … and that the judge in these circumstances is very much reliant on a very fast reading of the application and the evidence in support of it.”

Stephen’s injunction was overturned when the judge ruled that the housing association had failed to lay out the full details of the case. But, worn down by the process, he and his wife moved out of their home of over two decades. “That injunction has impacted me and my wife’s life so much, it’s unbelievable,” he told the Bureau. “It has basically ruined our lives.”

Simeon Wilmore is the solicitor who took on both Stephen and Diana’s cases; in both instances he believes an injunction was not appropriate action. “Prison should only be for the most serious of cases,” he said. “It can’t be right that someone is imprisoned for playing music too loudly, or generally being a nuisance. … Mental health support or mediation would be a far more cost-effective way of dealing with [these] issues.”

Fixing the system?

In July 2020 the Civil Justice Council (CJC), an advisory non-departmental public body, published a report that warned civil injunctions for antisocial behaviour were not working and that the system required “immediate and significant redress”. The report laid out 15 recommendations, including the urgent introduction of data collection. But two years on, virtually nothing has changed.

For people with mental health issues, part of the problem is that these injunctions are processed in the civil courts rather than criminal. In criminal courts, defendants are assessed by a programme called NHS Liaison and Diversion, which has access to medical records and can identify people with mental health issues, learning disabilities or other vulnerabilities and provide support.

In its 2020 report, the CJC recommended government departments “meet as a matter of urgency” to discuss how the civil courts could access these services too, but Nadine Dorries, then minister for patient safety, suicide prevention and mental health, said restraints on the NHS meant this would not be possible. Last month, however, the CJC told the Bureau that there has been recent engagement with NHS England over piloting the service in civil courts, which it said was “very welcome”.

Rheian Davies, head of legal at the mental health charity Mind, told the Bureau: “A joined-up approach, which understands the intersection between mental health services and the legal system, is absolutely essential to get people the support and help they need at an early stage to avoid these dreadful situations.”

Another limitation of contempt hearings in civil court is the sentencing possibilities. If the judge decides the person has breached an injunction, and is therefore in contempt of court, they have just two options: a fine or a prison sentence (which may be suspended). By comparison, judges addressing criminal cases can sentence people to community service, drug rehabilitation or mental health treatment.

The Law Commission is now undertaking a consultation into whether the current contempt of court rules are working.

Rona Epstein, an academic who has been researching the use of antisocial behaviour injunctions for years, told the Bureau: “The law regarding punishment for breaching antisocial behaviour injunctions is basically unjust, cruel. It should be repealed.

“Our prisons are very costly to run. They are there for those who have committed the most serious crimes which have caused the most serious damage. Antisocial behaviour is a problem. Imprisonment is not the solution.”

Reporter: Maeve McClenaghan

With thanks to: Rona Epstein

Community organiser: Emiliano Mellino

Bureau Local editor: Emily Wilson

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Alex Hess

Fact checker: Vicky Gayle

Illustrations: Ricardo Tomás

This project is funded by the Legal Education Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: