Lack of affordable lets leaves families with little left to live on

Three years since the Bureau first investigated, housing benefit rates still fall short across the country

It is impossible for those on housing benefits to rent a home across large swathes of Britain, according to new research from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism. The situation has left some cutting back on heating and dipping into other benefits to meet their housing costs.

A Bureau analysis of tens of thousands of rental properties shows 98% of those advertised over a single month were beyond the means of people in receipt of universal credit or housing benefit.

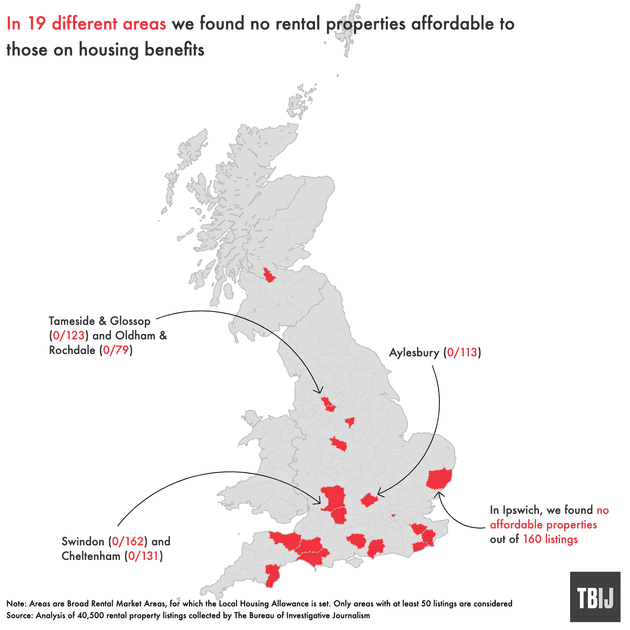

As the cost of living crisis bites and rental prices skyrocket, the Bureau has looked at the details from more than 40,000 rental adverts, comparing them to the regionalised rates of local housing allowance (LHA), which calculates the maximum amount of money you can claim on benefits towards your housing costs. We looked for all the two-bedroom properties up for rent at the time, as that is the most common kind of property rented by those on universal credit or housing benefit. In 19 areas across Britain – including central London, Swindon, Ipswich and Tameside – we did not find a single affordable property throughout all of July.

Polly Neate, chief executive of the housing charity Shelter, said: “These findings back up what we are seeing in our frontline services every day – that finding a safe home if you are on a low income is now like trying to find a needle in a haystack. Housing benefit should be the safety net that stops people becoming homeless, but it’s frozen at 2020 levels, leaving renters desperately trying to make up the shortfall … The housing emergency is at the core of the cost of living crisis, but it is being ignored.”

Major cities like Bristol and Cardiff had just one affordable property advertised during the entire month.

Charles Boutaud

Charles Boutaud

LHA rates were raised in April 2020, by the then chancellor Rishi Sunak, but they have remained frozen since, despite rental costs soaring. According to the online property portal Rightmove, average asking rents outside London have jumped by 19% since the start of the pandemic – the equivalent to eight years of growth previously – and are predicted to keep rising. On TikTok and Twitter, prospective renters complain of properties snapped up in hours and bidding wars, with some landlords accepting much more than the advertised rental price.

LHA rates are intended to cover the cheapest 30% of the private rental market. However, our analysis suggests that across Britain it can pay for only 2% of properties available to rent.

On average, LHA would need to be increased by £194 a month to meet the 30% target. But in some areas it was much more – those looking to rent a two-bedroom property in central London would need an additional £1,444 a month.

Angela, who is 76 and lives in North Yorkshire, is retired and receives housing benefit as well as disability benefits and her pension. Every month she finds herself having to dip into her other benefits to top up the £200 shortfall in her LHA.

Angela’s rent is £200 more than her housing benefit, forcing her to dip into her pension every month

Carole Poirot for the Bureau

Angela’s rent is £200 more than her housing benefit, forcing her to dip into her pension every month

Carole Poirot for the Bureau

‘What more can we cut down on? We don’t have the heating on unless we’re absolutely cold’

Carole Poirot for the Bureau

‘What more can we cut down on? We don’t have the heating on unless we’re absolutely cold’

Carole Poirot for the Bureau

“You have to rob Peter to pay Paul,” she said. “What more can we cut down on? We don’t have the heating on unless we’re absolutely cold ... if I go out socialising it has to be somewhere that is basically free.” She has tried looking for somewhere cheaper to rent but has found it virtually impossible.

Even some of the few properties that were affordable in our search were still inaccessible. We contacted scores of landlords and agents, posing as a single mother claiming housing benefit looking to rent a two-bed property, and made it clear that she could afford the rent.

Only 10 agents answered our question. Of them, two (both in Scotland) said the landlord would not rent to anyone on benefits; five said the renter would need a guarantor; one said our case study would need to earn at least 30 times the monthly rent annually, and just two said explicitly that the landlord would consider renting to someone on benefits. Even then, one qualified their position: “You do need to be able to evidence an annual income of £18,000 plus.”

Anny Cullum, policy and research officer at the Acorn renters union, told the Bureau: “The problem of housing benefits discrimination remains, and while it is illegal to discriminate directly against benefit claimants, it’s often difficult to prove this and enforcement from local authorities is lacking.

“These findings also make it clear that rents are far too high. If the government is serious about getting a handle on the growing housing crisis, they need to work to bring down spiralling rents which are increasingly inaccessible to many people.”

‘How are people supposed to live?’

Grace*, 38, has lived in Havering, on the outskirts of London for the past nine years. She worked in travel and lost her job because of the pandemic; she also broke up with her partner. She is renting with her two sons, one of whom is autistic and needs his own bedroom.

Grace has been topping up the money she receives for housing costs by £50 a month because the rate of LHA in her area does not cover her rent. This extra money has to be taken from her other benefits to make up the shortfall. “£50 can go a long way, it can feed us for a week if we’re savvy,” she said.

But now her landlord is selling his property, Grace has to find somewhere else affordable to live. She has been looking for more than a month and constantly makes enquiries about properties, but has not been offered a single viewing. “I check Rightmove 10 to 15 times a day, just to see if anything has come on there that is suitable for us,” she said. “Rents have shot up in the last 18 months … it is an absolute nightmare.”

Out of 350 two-bed property ads the Bureau found in the area, just 10 were affordable on the local allowance.

Some of the three-bed properties Grace has found cost £300 more a month than she receives in housing benefits. “I don’t know where I’m going to find £300 from, I really don’t … but we need somewhere to live.” She does not want to move out of the area; her son with autism has a local education and health care plan and the boys live close to their father.

“My first question is does the landlord accept universal credit … But because I’m on universal credit they are not really interested.” One agent told her the landlord would not accept anyone on benefits for insurance reasons and because of the backlog in eviction hearings against tenants who default on rent. “That’s not what I am planning on doing,” Grace said. “They are tarring everyone with the same brush.”

She has asked her current landlord to give her a Section 21 notice – a no-fault eviction notice – as she thinks that could help her access homelessness support. She has looked into applying for discretionary housing payments from the council. It is risky, she explained, “because they don’t have to [accept you], it’s discretionary”.

“I can’t believe local housing allowance has been ignored … I just don’t understand how people are supposed to live.”

Discretionary housing payments

Discretionary housing payments (DHP) are one of the few lifelines for those struggling with housing costs in England and Wales. This money can be awarded by local authorities to top up any shortfall between a claimant’s benefits and their rent. However, the latest statistics from the Department for Work and Pensions show large discrepancies in how much of this funding different councils distribute.

Tewkesbury allocated just 29% of their potential funding pot to those asking for DHP. The town covers two different broad market rental areas, the map regions used to determine housing allowance levels: Cheltenham and Gloucester. The Bureau did not find a single affordable property in the Cheltenham area out of 131 two-bedroom properties advertised. The area would need an extra £205 a month to make the bottom 30% of rentals advertised affordable. In the Gloucester band there were four affordable properties out of 92 advertised, and an extra £150 a month was needed.

Graeme Simpson, Tewkesbury Borough Council’s head of corporate services, told the Bureau: “We have clear criteria for payments to ensure we are consistent when supporting our most vulnerable residents. When we receive an application, a dedicated officer reviews the information provided and carries out an affordability check. On occasion, we do have to refuse an application because the household has demonstrated it has sufficient disposable income to afford the rent without assistance.” He said the council had other ways of helping those most in need, such as a homelessness prevention grant.

In comparison, other councils quickly burn through the DHP funding that they are allocated by Westminster. Stephanie Cryan, the cabinet member for finance, democracy and digital at Southwark Council, recently told a parliamentary select committee: “We have a discretionary housing fund … We spend the amount we get from that by Christmas, so there are four months of the year where we have nothing to give people. It is a real struggle.”

A government spokesperson said: “During the pandemic we increased the local housing allowance for housing benefits, with 1.5 million households receiving on average an additional £600 a year. We are maintaining this boost, ensuring those who benefitted will continue to do so, whilst also investing £11.5 billion in our affordable homes programme.

“We have also taken action to support the most vulnerable with direct payments worth at least £1,200 while our new energy price guarantee, saving households on average a further £1,000, will help people to pay their bills.”

*Name has been changed

Header image: A lettings agent window in Leeds where every property is already let. Credit: Daniel Harvey Gonzalez/In Pictures via Getty Image

Reporting team: Maeve McClenaghan, Charles Boutaud and Vicky Gayle

Data visualisation: Charles Boutaud

Community organiser: Emiliano Mellino

Bureau Local editor: Emily Wilson

Editor: Meirion Jones

Production editor: Frankie Goodway and Emily Goddard

Fact checker: Niamh McIntyre

Our Bureau Local project has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Area:

-

Subject: