The problem with extractive journalism

I never liked working with journalists.

Ten years as a campaigner with local and international NGOs will do that to you.

After facilitating hundreds of interactions between reporters and survivors of torture, sex trafficking and immigration detention, I came to develop a deep-seated (and potentially unhealthy) distrust of journalists.

Time and again, they would parachute in, extract what they or their editors deemed “valuable”, relay it to an audience elsewhere, only to be next seen again picking up shiny individual gongs for their work highlighting these systemic abuses.

Time and again, they would unwittingly perpetuate the very power imbalances they sought to expose, reducing people to ‘case studies’, stripping them of agency and giving them no control over how they were represented.

Time and again, they would compound narratives of victimhood that subsequently helped justify policy responses from decision-makers that were acts of charity rather than justice.

The way some major broadcasters reported on people trying to reach the UK in dinghies off Dover this week was a perfect example of these kinds of approaches. A correspondent sailed in front of them, doing a piece-to-camera as they bailed out water from their boat. It felt voyeuristic, dehumanising and exploitative; like an attempt to capitalise on suffering in a bid for clicks and hits.

Besides the very real mental or legal danger this kind of journalism often presents to survivors, my discomfort with the reporters I worked with also stemmed from the acknowledgement that, ultimately, we needed them. Systems change rarely happens in a silo: it nearly always demands an ecosystem of different actors, and journalism has a particular and vital role to play. In the words of Ida B Wells, the American investigative journalist and civil rights leader: “The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press.”

That is a large part of why, despite readily brawling with journalists for the last decade, I suddenly find myself surrounded by them here at the Bureau, in the newly-created position of Impact Producer and Community Manager on our Global Health team. The health team is also new, and has been set up with the specific aim of fostering collaborative cross-border investigations that have the potential to ‘come off the page’ and make a difference in the real world.

The heath team's first major investigation examined why global drug supply chains are so fragile and opaque

The heath team's first major investigation examined why global drug supply chains are so fragile and opaque

I was drawn to the job because I believe this kind of approach offers an opportunity to be part of re-imagining what journalism might look like. I was drawn to the job because that re-imagining feels absolutely urgent as traditional media crumbles around us, misinformation weeds the cracks, and the deficit of trust between newsmakers and their public continues to swell. I was drawn to the job because I felt that those two words in the job title – Impact and Community – signposted a way out.

The Bureau’s commitment to produce journalism with impact means not only being purposeful in trying to expose wrongs, evidence abuses and challenge narratives, but also to think strategically about how our work can equip campaigners with our evidence and engage affected communities before, during and beyond publication. It puts a premium on our work being useful and this represents a (refreshing) move away from ‘journalism for the sake of journalism’, where success is measured in terms of the reach of a story as opposed to what people might actually do once they’ve consumed it.

For me, the dual onus on community relates directly back to the impact. I am coming fresh from the NGO world where there is a realisation that the traditional advocacy model, where experts recommend policy changes, needs to be replaced by more participatory approaches. Rooted in practices of community organising and movement-building, these approaches see NGOs go much further than advocating on behalf of affected communities; instead they actively support those individuals to organise and advocate for themselves. This is the only way to ensure power relations are transformed and, crucially, that the change brought about is sustainable.

A quick look back at the kind of impact that the Black Lives Matter movement has had over the last few months – from policy changes to resignations to the sheer number of white-dominated spaces (the Bureau included) actively reassessing their own power and privilege – stands as just one example in a long, long list of what grassroots, bottom-up initiatives can achieve.

Thinking of how this relates to journalism, City Bureau, Outlier Media, Free Press and our very own Bureau Local offer good examples of how similar principles might be applied: stories start and end in the community; the community themselves determine what information is ‘valuable’; community members are engaged as the co-creators of stories as well as the key audiences for them; innovative techniques are used to find and tell stories in ways that are both accessible and useful. Press On Media sums this up as “using journalism as a tool to support social justice organising, and to use organising as a tool to transform the field of journalism.”

This feels like an important part of any future public interest journalism that is genuinely interested in its public. And as any number of Bureau Local’s investigations would attest, this approach has as much to do with impact as it has to do with being consistent with publicly stated principles about accountability journalism. It is another clear demonstration of impact through community.

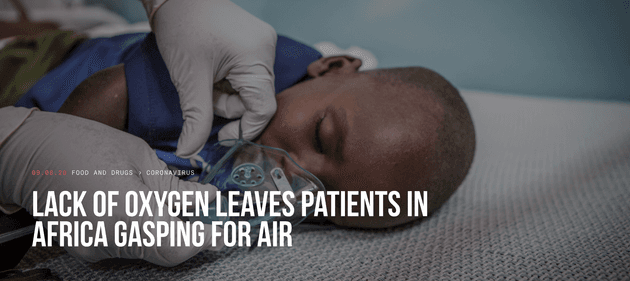

The health team's most recent investigation looked at oxygen shortages across Africa and the prices charged by the multinational companies which dominate the market

The health team's most recent investigation looked at oxygen shortages across Africa and the prices charged by the multinational companies which dominate the market

Just as is the case with NGO advocacy, this is not to dismiss top-down policy change as redundant; of course that remains a significant part of creating the best conditions for social change to take place. And we should be honest about the fact that in some instances the Bureau may be much better placed to help enable top-down rather than bottom-up change.

However we must acknowledge that policy changes will always have a better chance of actually lasting if they are shored up by popular support and public pressure, and this in turn should inform the journalism we do.

Some of the key questions then for me as I go forward in this new role focus on what we can learn from initiatives like Bureau Local, and how these learnings might be applied on a global scale. What does community-led journalism look like when global health can affect millions of people at any given time? Who gets to decide which investigations we focus on? How can we engage different kinds of communities across the world in a way that doesn’t echo the worst tendencies of extractive journalism? How can we do all this based out of an office in London? How can we help ensure that the social changes that people want last beyond the shelf-life of an investigation or the symbolic tweak to a policy?

The Global Health team is busily brainstorming answers to these questions but, in line with basic principles of community organising – to not presume what is necessary or valuable but to go out and ask – we are very keen to hear from others working across global health, community journalism, community organising, cross-border reporting, impact production and anyone at all who might have ideas about how we can make more of a difference in our work. Get in touch with Ben du Preez via email at [email protected].

Exposing systemic failings through investigative journalism isn’t a quick fix. It takes time to uncover the evidence. It takes time to get people to notice. But when we take that time, we can get results. Help us do more.

Support the Bureau today