The race to house Britain's homeless

After an unprecedented effort to get ‘Everyone In’, the long-term fate of the homeless is uncertain

On the Thursday before Easter, Sam Dorney-Smith breathed a sigh of relief. But the healthcare nurse, at that point overseeing the care of about 350 homeless people moved out of shelters and into 13 hotels across London, was not relaxing in anticipation of a bank holiday.

For three weeks homeless people showing symptoms of Covid-19 could not be admitted to the hotels. Instead, Dorney-Smith said, outreach workers had to approach local councils and try to negotiate accommodation for each person. Now, finally, that had changed.

The hotels that the Greater London Authority (GLA) had managed to secure were only for people who showed no symptoms of the disease. It had planned to put all symptomatic homeless people in one hotel, with medical care on-site, but negotiations with hotels and NHS trusts with vacant buildings had not been successful.

Earlier that week, Dorney-Smith had been clearly worried. She did not know how many people with Covid symptoms were on the street, but told the Bureau: “We need a specialist hotel to get those people in so that they can receive the best care.”

On Thursday April 9, Dorney-Smith heard good news. A facility was finally found and by the next week, symptomatic homeless people could start being moved after the Easter weekend.

The GLA said a hotel for symptomatic homeless people began admitting guests on April 14. However, it said that several of the other hotels which had already opened had floors designated for people who showed symptoms.

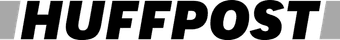

This is just one story from the unprecedented “Everyone In” policy rolled-out across the UK over the past six weeks. The government claims that 5,400 people have been offered emergency accommodation in hotels and B&Bs, which it says is 90% of rough sleepers known to councils at the beginning of the crisis. In Wales, more than 500 people have been moved into emergency accommodation since the pandemic started, with handfuls left on the street in each local authority. And in Scotland, Holyrood said outreach services were reporting that there are fewer than 30 rough sleepers left across the country, with about 200 people accommodated in hotels.

There has been an unprecedented effort to house the homeless across the UK and yet future support is uncertain.

Bureau Local, working with our network of journalists and engaged citizens, has discovered that:

- Organising a quick response was difficult. It took three weeks for the Greater London Authority to open a suitable hotel for homeless people with symptoms of Covid-19;

- Wales, a country with a population one eighteenth that of England, ringfenced £10m to house and protect homeless people during the pandemic, three times the amount ringfenced by Westminster;

- Contracts with hotels to house rough sleepers expire next month. In England, there is no long-term funding for the emergency hotels;

- The Greater London Authority is trying to negotiate extensions to their hotel contracts and find the money to finance them; local authorities across England will be left to do the same.

- Crisis, the homelessness charity, said “the job simply isn’t finished”. They estimate the cost of housing those currently in English hotels at £97m.

“It’s completely unacceptable that people are being left abandoned on our streets, and that people are at risk of being kicked out of hotels because councils lack the funds for them to stay… the job simply isn’t finished,” said Jon Sparkes, chief executive of Crisis.

“The initial emergency response to the outbreak showed what can be done when the political will and leadership from central government is there - but if we retreat into a failed ‘business as usual’, handing the issue back to overstretched local councils with no ring-fenced funding, then we let down not just the thousands experiencing homelessness today, but many thousands more at risk from the economic downturn we are entering.”

Outrunning disaster

As the deadly toll of coronavirus became known, it was clear that national governments and local authorities were locked in a race to prevent the virus from ripping through a group much more vulnerable to the infection than the general population. People experiencing homelessness are three times more likely to experience a chronic health condition including respiratory conditions such as COPD, according to Crisis, as well as reduced life expectancy – 45 for men and 43 for women. In addition to rough sleepers, there were also almost 35,000 beds in temporary accommodation for single homeless people in England to be made safe as people prepared for a long lockdown.

London was swift to address the needs of its homeless population. The closure of winter night shelters, which under normal circumstances tend to close in late March or early April, was looming on the horizon. This would have seen the number of rough sleepers surge just as the rest of the country was being told “Stay At Home ... Save Lives”. In London alone there are nearly 4,000 people living on the street who take respite in the shelters, sometimes sleeping closely together on floors, beds and in sleeping pods.

The GLA’s approach was influenced by a plan called “Test Triage Assess Cohort Care”, which had been outlined only a week before on March 12 at a conference held by the homeless health organisation Pathways. Designed by Dr Al Story and Professor Andrew Hayward, experts in the health of homeless populations, it separates homeless people into three groups: those with Covid-19 symptoms; the over-55s and those with medical vulnerabilities; and everyone else. The process is called cohorting.

“If we can cohort effectively it will make an enormous impact on the delay in terms of how explosive the outbreak becomes,” Story told the conference.

A week later, by March 21, the GLA had secured two hotels from the Intercontinental Hotel Group and the process of moving people from the shelters began.

While London forged ahead, a national plan was yet to be announced, at a time when every moment counted. On March 17 Robert Jenrick, the communities secretary, had announced £3.2m for English councils to help homeless people self-isolate, but charities and health professionals said there was no clear guidance on how to do this, even as shelters and day centres in some parts of the country closed.

It took nine days, during which time the number of confirmed cases rose over four-fold, for Luke Hall, the minister for homelessness, to contact local leaders and ask that they book accommodation for rough sleepers and get everyone in by the end of the weekend. He added that councils could draw on £1.6bn in funding made available for the emergency. Later, another pot of £1.6bn was announced. But homelessness may struggle to secure its piece of the pie as councils struggle to meet competing demands, including funding adult social care, from ever-shrinking budgets.

England v Wales

In Wales, the government took an early lead. On March 9, Julie James, the Welsh housing minister, met with the homeless sector to hear what the challenges and concerns were in the event of a pandemic outbreak. Three days after Jenrick announced £3.2m for rough sleepers in England, James announced £10m of ringfenced money for Wales, a country with one-eighteenth of England’s population.

She was clear that the money was to help all homeless people, including some groups that in England were beginning to fall through the net, such as those with No Recourse To Public Funds (NRPF), an immigration status that applies to thousands across the UK and denies them access to housing and welfare benefits.

Katie Dalton is the head of Cymorth Cymru, the representative body for the homeless sector in Wales. She said: “Early on in this pandemic the Welsh housing minister made a strong commitment to getting people off the streets and into emergency accommodation, including people with No Recourse to Public Funds.”

Westminster also told English local authorities to house NRPF cases – but confusion soon set in over what money they should use to do so while the usual Home Office restrictions applied.

Jessie Seal, of Naccom, a support network for asylum seekers, told the Bureau that one council had issued eviction proceedings on six people with No Recourse to Public Funds who had been housed only weeks earlier, because it said it was expecting guidance from the government that would relieve it of its duties. The eviction has since been temporarily rescinded. The Bureau has heard that at least 13 councils across the UK have refused to accommodate NRPF cases. About 900 of the rough sleepers housed in London are thought to be NRPF cases.

Got a Story?

We welcome tip-offs from the public and we always protect our sources

Find out how to work with usIn Wales, the ringfenced £10m may have made it easier to house people. Local authorities were given flexibility to spend on things that would help to get people into accommodation, from block-booking rooms in hotels and B&Bs to purchasing fridges and furniture. Crucially, Katie Dalton said, the money was not just for housing, but to provide support to people through the crisis.

Radical action was taken early. Housing associations made accommodation available – one, Cadwyn Housing Association, turned its shipping container developments in Ely and Butetown from accommodation for homeless families to a quarantine facility for symptomatic rough sleepers.

A Welsh government spokeswoman said: “Helping vulnerable people into accommodation so they can access handwashing and hygiene facilities, can social distance and self-isolate if they have symptoms has been the main focus of the work by local authorities. But we have been clear about the importance of supporting people longer term and of working with people to address their often complex needs and to develop and implement rehousing plans.

“We are working with the sector on plans to ensure no one is forced to return to the streets. This will mean a mix of temporary, supported and long-term accommodation options.”

A source close to the process in Wales told Bureau Local that the limited funding offered to English councils, and the sudden demand that people be moved into accommodation over a single weekend, was puzzling. “It seemed more like a publicity stunt.”

Everyone In?

Across the UK Bureau Local heard stories of how councils had met – or tried to meet – the “Everyone In” brief.

In Birmingham, people have been placed in hostels and hotels around the city, with those self-reporting symptoms now living in a Holiday Inn. People with addiction issues or No Recourse to Public Funds have been included in Birmingham’s plan, and the number of people on the streets has dropped to about a dozen – although begging was picking up again.

However, a staff member at a hostel housing 130 people said they felt their facility had been forgotten about in the crisis, despite the fact there were rooms available and PPE on hand for guests.

As-Suffa, an outreach service, has begun delivering food to newly housed people where provision is patchy, and to those in shared accommodation. The group told Bureau Local that it had also seen demand grow for its listening service, which provides emotional and legal support to rough sleepers, since the hotel scheme began.

In Great Yarmouth, a seaside town, the council stepped up and housed not only 43 identified rough sleepers, but another 34 people deemed as being at risk of rough sleeping.

Some are thinking even further ahead: in Thanet in Kent, people are already being moved out from the hotels into secure accommodation.

But other stories were much more worrying. In Manchester, according to the Guardian, up to a quarter of those placed in hotels have abandoned their accommodation, and the Bureau was told women were still using sex work to fund drug habits, alongside hospitality workers who had lost both their homes and their jobs turning to sex work to survive.

Long term plans - English v Scottish approach

In Scotland, the Simon Community, which is running three hotels for around 140 homeless people across Glasgow and Edinburgh, told the Bureau that the street homeless population was in the single digits in both cities. In addition to the hotels, both cities have upped their use of managed flats and B&Bs, especially for homeless families.

The Simon Community said that those moved into hotels were seeing enormous benefits; people suffering from addiction were accessing treatment for the first time and, in an unforeseen silver lining to social distancing measures, could not be in contact with drug dealers.

As the English government leaves questions unanswered about those living in the hotels, Holyrood has brought forward plans to ensure people are moved into their own homes much more quickly. They have announced that from October, someone can only spend seven days in temporary accommodation before they must be moved to long-term accommodation.

“We know that providing people with a settled home, and the support they need, is the best way of solving homelessness. That’s why a rapid rehousing approach will remain our focus in the months ahead,” Kevin Stewart, the Scottish housing minister, told the Bureau.

Tell us more

These are just some reports of how “Everyone In” has been rolled out. We’d like to hear how your area tackled housing and supporting homeless people – and what plans you’ve heard for once lockdown lifts.

Get in touch

Gaps in the system

While Wales and Scotland have sought to support the wider homeless population, including those in temporary accommodation, in England the focus has been on rough sleepers.

“What we’re starting to worry about is that, while that cohort has been made safe, there are still people rough sleeping, and there will be new people rough sleeping as well. I’m not sure yet that the government is ahead of this,” Jon Sparkes from Crisis said.

The system is struggling to keep up with a crisis that is still in motion, and it is leaving behind people who need help.

Two people who know about that are Dexter and Mariusz, who spoke to Bureau Local late one night towards the end of April. They live in tents outside Heal’s, an upmarket furniture store in central London. They have formed a tight unit, hunkering down together to survive the streets in quickly worsening conditions.

Dexter, 46, is a veteran bar manager. When he split up with his wife, he lost his accommodation too, and has been homeless since January. “I just need one leg up,” he said. He has a work coach, and has heard about jobs at Tesco he could do, but he needs a place to live.

Mariusz is 28 and worked in bars and on the festival circuit. When lockdown was announced, his work disappeared.

Dexter and Mariusz have waited for a hotel room for weeks

Franc Vissers

Dexter and Mariusz have waited for a hotel room for weeks

Franc Vissers

The stress of the situation has left the pair distraught and despondent

Franc Vissers

The stress of the situation has left the pair distraught and despondent

Franc Vissers

They say they’ve been waiting for a hotel room for over five weeks. Neither man was in the shelter system, so they were not housed by the GLA when the hotel scheme began, and have played catch-up ever since. They have been seen by Camden’s homelessness service Routes Off The Streets, but say they now feel forgotten about.

Mariusz wept as he described the toll of living on the streets under lockdown - with shops, bars and day centres closed, there is nowhere to even use a toilet. “Why have we been left?”

For Dexter, despondency was setting in. “I’m going to be stuck on the streets forever. I don’t want to spend the rest of my life out here.”

There are at least 500 people left on the streets in London, according to the GLA. The Bureau Local met some on outreach with Under One Sky, which has been delivering about 250 meals a night in four areas of central London. Some people do not want to move into hotels; one man said he was too scared of his own mental health to be alone in a hotel room. Another said that bad experiences with hostels had put him off, and he had got round the lack of showers by washing early in a park’s fountains.

But many do want to be accommodated. There are reports across the UK of gig economy workers like Mariusz who have been left newly homeless on the streets. But the hotels secured by the GLA are nearly full and although another 200-bed property was booked over the weekend, the authority expects it to be filled this week.

Looking beyond the streets, there are 62,000 families living in temporary accommodation in England, a number that has increased by a third in the past five years. It is an already grim part of the creaking housing system that has been put under additional pressure and made life harder for people already barely able to cope.

One woman, who has been living in temporary accommodation for two years, told Bureau Local that her attempts to keep the block safe during the crisis had been rebuffed by the council. She had suggested a tougher cleaning regime and a buddy system between tenants, some of whom are disabled. At least one person in the block had the virus, and someone else was discovered dead in their flat two weeks ago, although there was no known link to Covid-19. She said she felt the tenants had been left to fend for themselves.

Already in London, the number of people presenting as homeless to local authorities is returning to pre-lockdown levels, according to evidence given to the Housing select committee this week. More than 2,500 people who said they were homeless or at risk of homelessness approached councils in the first week of May.

Life after lockdown

Mark has been homeless for three years. He had shared a home with his father, but when he died Mark was unable to keep up with the rent. He slept in a car with no heating for months. “When I saw the ice on the inside one day I thought, this is getting a bit cold.” Last year he started sleeping on night buses.

Before the GLA announced its hotels plan, Mark had anxiously watched the facilities he depended on closing one by one. “When you're homeless, even in a night shelter you rely upon certain services like McDonald's and libraries and leisure centres,” he said.

He was especially concerned by the closure of the community centre where he would normally get a shower and free food in the morning, and could stay warm in the day. Then the library shut too. “We were all finding that all the facilities were closing one by one and it was becoming extremely difficult.”

His usual alternatives, trains and buses, meant risking infection. “You're always mixing with other people.”

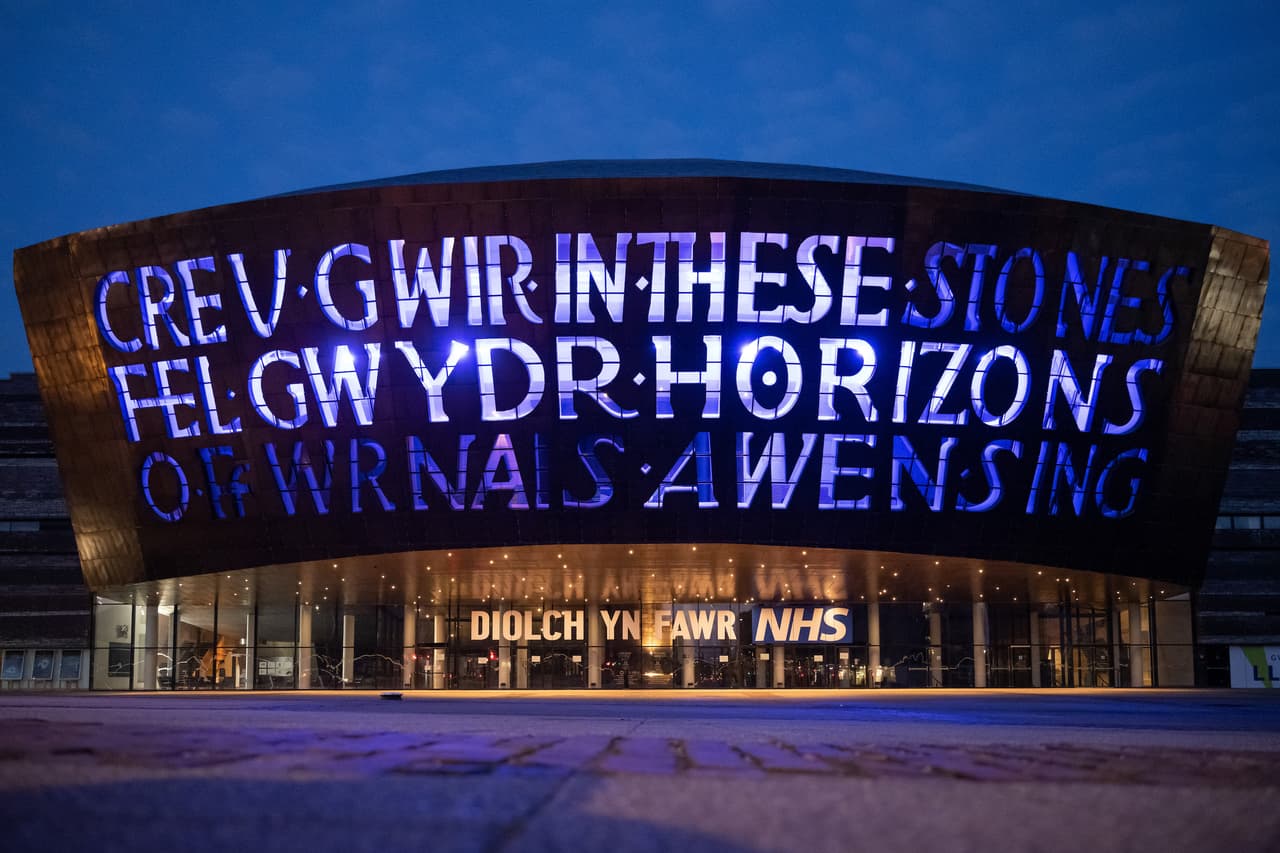

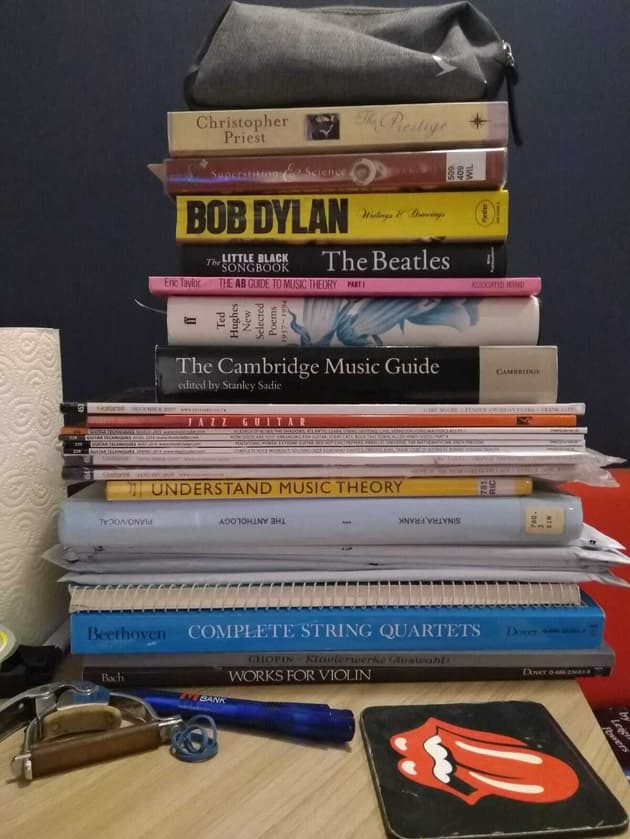

However, Mark was in a winter night shelter system operated by Glassdoor, and so was part of the first tranche of people accommodated in London.

“For me this is fantastic,” he said over the phone from his hotel. For once he can avoid the stress of being permanently on the move, and can enjoy old hobbies like the guitar, and even learning music theory. “It's a bit more like normal life,” he said, “funnily enough, in a time when everyone else is not having a normal life.”

Mark has been using the stability of life in the hotel to work on music theory and the guitar

Mark for the Bureau

Mark has been using the stability of life in the hotel to work on music theory and the guitar

Mark for the Bureau

Mark for the Bureau

Mark for the Bureau

It is an improvement it would be devastating to lose. People working in the homelessness sector are concerned about what happens next to all the people who have managed to get inside.

Crisis told the Bureau that the first estimate of the cost of supporting everyone taken off the streets so far into proper, permanent accommodation was £97m over a year.

That costing allows for half of the 5,400 people currently in hotels needing Housing First accommodation, which is specialist housing with dedicated support, for example for those with addiction or long-standing mental health issues. The rest are expected to need some level of support to secure a tenancy. Ultimately, Crisis estimates that spending £34m on housing benefit and £63m on support could move a huge number of Britain’s rough sleepers into real homes.

Yet Sparkes cautioned against focusing solely on that group. The charity’s estimate does not account for people becoming homeless in the coming weeks.

“The big building blocks of ending homelessness; building lots more social homes, and a much more sympathetic welfare system, are still big asks that need answering,” he said.

Of her 27 years as a nurse, Sam Dorney-Smith has spent 16 working in homeless healthcare. She said that progress with clients depends upon building relationships. With hundreds of people in a hotel, there is room for productive conversations to take place. But the Bureau has heard that some of the contracts negotiated with London hotels are due to end on June 1 or July 1 and Dorney-Smith has not heard about any extensions. “It would seem incredibly self-defeating,” she told the Bureau, “if the engagement work was not able to continue.”

The Manchester Evening News (MEN) obtained a leaked report given to the region’s combined authority revealing that the Ministry for Communities, Housing and Local Government (MHCLG) will not be financially supporting homeless accommodation in the long-term. They report that the document stated:

“MHCLG have drawn a line under ‘Everyone In’ activity and is now asking local authorities to focus on ‘step down’ and ‘move on’ for those who have been accommodated as a result.”

The Bureau has also been told that in London, there was no expectation of long-term funding for the hotel system. Charities in the GLA-run hotels had heard MHCLG funding was coming to an end and that existing contracts with hotels were unlikely to continue. They worry that those on NRPF or those without documentation - many of whom are being supported under the COVID-19 scheme, will no longer be able to receive housing.

MHCLG did not provide a comment. They have said on Twitter: “We have been clear councils must continue to provide safe accommodation for those that need it.”

The GLA said: “Negotiations about possible extensions are underway ... Understandably, some hoteliers were awaiting announcements on the next stage of lockdown before entering into these negotiations.”

Dorney-Smith said she was encouraged by the appointment of Dame Louise Casey to head up a new homelessness taskforce charged with ensuring that rough sleepers housed during the crisis will move into long-term accommodation once lockdown is over. Dame Louise is no stranger to this issue, having been the head of Tony Blair’s Rough Sleepers Unit in 1999. But today, the numbers are very different. There are more than two and a half times as many homeless people today as there were before 2010 - and that’s just counting street homelessness.

She cautioned that moving people into permanent homes would be complex. The hotel scheme had, she said, unearthed “hidden people” whose rights and mental and physical needs would take time to untangle.

Back in his room, three weeks ago, Mark said he believed a positive outcome was coming his way. He had just seen a support worker who told him: “Whatever happens, we won't be abandoning you any time soon.”

Will they be able to keep their promise? Without long-term funding, the future of Britain’s homeless now sits with under-funded and over-stretched local councils and charities.

Share this story: With your friends, community and MP

Join the investigation: Sign up to the Bureau Local and help us collect plans from your local council

Tell your story: Share a personal story of this issue by emailing: [email protected]

Additional reporting by:

- Julia Gregory, My London Online

- Kathy Bailes, The Isle of Thanet News

- Emily Townstead and Tom Bristow, East Anglian Daily Times

- Alice Milliken, freelance journalist and researcher

Note - a few changes were made to this article on May 17 to improve clarity

Header image credit: Franc Vissers

Our reporting on the housing crisis is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. Our work on the housing crisis was supported by the Bertha Foundation. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.