‘I worked for Abramovich?’: footballers were owned by oligarch via offshore deals

Former Chelsea owner locked young players across Europe into contentious third-party contracts

The former Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich locked at least 21 young football players into controversial deals that controlled their careers, documents reveal.

An investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and international partners has established that the oligarch signed emerging talents as young as 16 into “third-party ownership” (TPO) agreements.

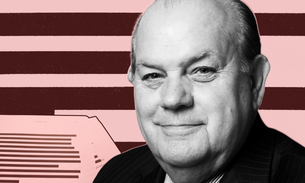

Several of the deals involved football “super-agent” Pini Zahavi, who files show had an exclusive investment agreement with Abramovich to source economic rights of players.

The arrangements, which were banned worldwide by football authorities in 2015, granted an investor the right to profit from a player’s career, including transfers.

The deals all appear to have been made before the ban, and Abramovich and Zahavi were already known to have dabbled in third-party ownership.

But the scale of the operation can be charted for the first time thanks to the Cyprus Confidential files, a cache of 3.6m leaked offshore records shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and Paper Trail Media.

The files also raise questions around how effectively the deals were unwound post-2015.

Documents show the deals meant at least one player whose economic rights appear to have been owned by Abramovich ended up playing against Chelsea in a 2017 Premier League match, in a potential conflict of interest.

Sports law experts say transactions in the documents may have breached Fifa’s third-party influence rules, which were introduced in 2008 and would have applied to the deals in question. They govern the ability of a business to influence the policy or performance of a football club.

They also lay bare the raw deal given to young footballers, who told reporters they were sucked in by grand promises that then evaporated. It’s impossible to know to what extent Abramovich’s influence meant the players didn’t reach their potential – but the deals show young footballers ceding control over their careers.

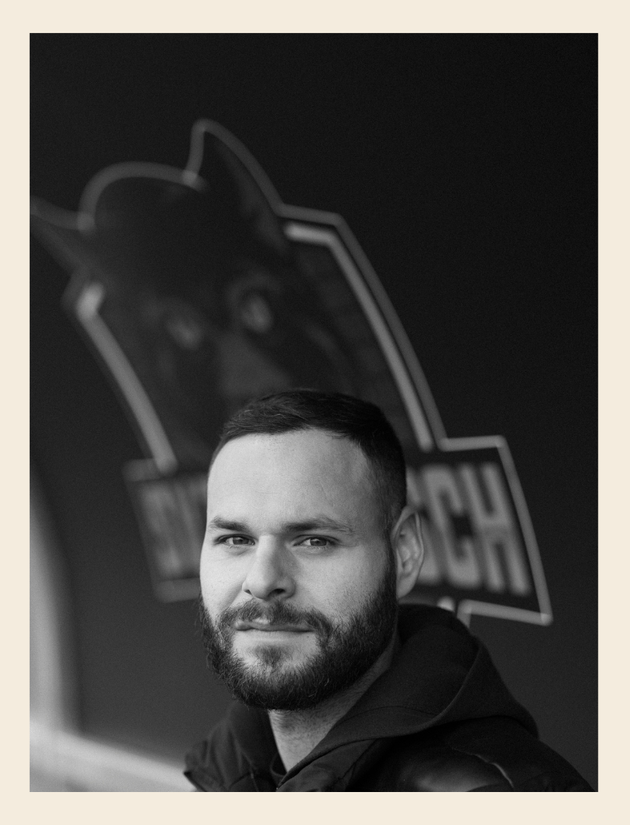

Emir Dautovic signed one such deal back in 2012, aged 17, when he was playing for NK Maribor in his native Slovenia.

Emir Dautovic signed away his economic rights when he was 17 years old

Elias Holzknecht

Emir Dautovic signed away his economic rights when he was 17 years old

Elias Holzknecht

He told reporters: ‘I didn’t know that a company was buying me’

Elias Holzknecht

He told reporters: ‘I didn’t know that a company was buying me’

Elias Holzknecht

Dautovic had impressed during a trial at Manchester City, he remembered, and a few months later Zahavi’s representative approached him with a deal. The middleman boasted the agent could “arrange a transfer to Chelsea overnight”.

“It was like getting onto the motorway in my career,” Dautovic said. “I didn't know that a company was buying me. All that was said to me was Pini Zahavi would become my agent and that was the best thing that could happen to me.”

The deal wouldn’t work out as he hoped.

The Abramovich-Zahavi partnership

As an agent, Zahavi has presided over some of the biggest deals in football, including the 2017 transfer of Brazilian forward Neymar Jr from Barcelona to Paris Saint-Germain for €222m.

According to a “player investment agreement” in 2011, Zahavi pledged to scour the world for talented players for a firm called Leiston Holdings, incorporated in the British Virgin Islands and owned by Abramovich.

He would buy the “exclusive right to fully exploit all of [the players’] commercial economic rights and interests”.

Leiston would invest up to €10m and if players were sold on at profit, Zahavi and Leiston would split the proceeds.

Documents show Dautovic was one of Leiston’s investments. He and his parents signed a contract under which his economic rights were sold to the company for €1m.

Dautovic wasn’t alone. Another of the players who signed with Abramovich companies said the deal stripped him of control over his future and left him earning a fraction of what he could have.

Many signed as teenagers, with several of them under 18, meaning their parents had to sign alongside them.

Leiston covered players’ salaries, but some were as low as €50,000 per season – well below the expected levels of potential stars. Nor did Leiston’s young stars appear able to exercise much influence over their careers.

The Cameroonian hopeful Fabrice Olinga became the youngest player to score in La Liga, Spain’s top division, when he played for Málaga FC aged 16 in 2012. He was snapped up by Leiston and Zahavi a year later.

Fabrice Olinga celebrating with his Málaga teammates after scoring against Celta in 2012

Miguel Riopa/AFP/Getty Images

Fabrice Olinga celebrating with his Málaga teammates after scoring against Celta in 2012

Miguel Riopa/AFP/Getty Images

In January 2014, Olinga’s fans asked him on Twitter about rumours he’d been sold by Malaga to the Cypriot club Apollon Limassol. Olinga responded to followers that this was a “lie”. But he was wrong.

The Limassol connection

The leaked files often show a pattern: after any dreams of signing with Chelsea evaporated, the unglamorous truth was often a move to Apollon Limassol FC in Cyprus – a club part-owned by Zahavi.

Olinga was one of six Leiston players transferred to the club, of whom only one ever played for them. Any aspirations of playing in Europe’s most prestigious leagues never came to pass and he now plays for FC Botosani, in Romania’s top division.

According to the sports law expert Antoine Duval, some of the Limassol deals raise serious questions about potential breaches of Fifa’s “Article 18bis”, which prohibits third parties from wielding influence over a club’s transfer policy.

In at least three cases Abramovich’s companies were granted “sole discretion with regard to the transfer” of the players.

“This clause is typically contrary to Fifa’s ban on third-party influence,” said Duval. “So, in this case, I believe Fifa … would consider that the club breached Article 18bis by entering into this contract.”

Out of the Blues

The Cyprus Confidential files also provide new insights into Chelsea’s own forays into third-party ownership.

Prior to the TPO ban, Chelsea had owned a stake in a Jersey entity called Burnaby Investments LP via a subsidiary. A 2014 investigation by The Guardian revealed Burnaby was also involved in buying the economic rights of footballers, including Ricky Van Wolfswinkel.

In June 2015, a month after Fifa’s TPO ban kicked in, Chelsea sold its stake in Burnaby to an Abramovich-owned BVI company for just under €10m.

But the agreement included a clause stating Abramovich’s company would in fact transfer 20% of any profits generated from future sales of economic rights back to the seller, Chelsea. Put another way, the Blues stood to profit from future transfers while the Jersey company remained off its books.

Van Wolfswinkel’s name appeared on later accounts compiled for Abramovich’s company, which stated that it made over $1m in profit following a sale in 2017.

It’s not known if Chelsea profited from this sale, as envisaged in the agreement.

Conflict of interest in the Premier League?

Sixty-five minutes into Chelsea’s match against Watford in October 2017, Abramovich’s club was down 2-1 until a Peruvian winger entered the fray for Watford.

André Carrillo appearing for Watford against Chelsea in October 2017

Ian Kington/AFP via Getty Images

André Carrillo appearing for Watford against Chelsea in October 2017

Ian Kington/AFP via Getty Images

In the half-hour after André Carrillo came onto the pitch, on loan from the Portuguese side Benfica, Chelsea overturned the deficit to win 4-2.

But Carrillo wasn’t just a Watford player. Leiston had bought 50% of his economic rights in 2011 and the player was still listed as an “intangible asset” worth nearly $1m in a company statement in 2019.

The potential conflict of Leiston’s investment in Carrillo was first reported by the BBC over two Champions League matches between Chelsea and Sporting CP in 2014. But the Cyprus Confidential files show for the first time the potential conflict of interest affected the Premier League too.

There is no suggestion Carrillo’s performance was affected by the ownership of his economic rights. He may not even have known of his link to Abramovich.

When he was approached by TBIJ’s international partners on this investigation, Emir Dautovic was playing for SV Tillmitsch, a local team in the fourth tier of Austrian football, and working for a frozen foods company.

“I worked for Abramovich? I’m taken aback by that. I swear, I didn’t know,” he said.

Abramovich did not return requests for comment. Zahavi denied any wrongdoing, but declined to comment further. NK Maribor responded to say the transactions were linked to individuals no longer working at the club.

Carrillo was contacted for comment. Watford FC said it had no knowledge of Leiston’s investment in Carrillo; there is no suggestion of wrongdoing by either party. Apollon Limassol did not return requests for comment.

A spokesperson for Chelsea FC said: “These allegations pre-date the Club’s current ownership. They are based on documents which the Club has not been shown and do not relate to any individual who is presently at the Club.” They added the club is assisting regulators with inquiries into incomplete financial reporting which were self-reported by Chelsea’s new owners.

Emir Dautovic now plays for SV Tillmitsch, a local team in the fourth tier of Austrian football

Elias Holzknecht

Emir Dautovic now plays for SV Tillmitsch, a local team in the fourth tier of Austrian football

Elias Holzknecht

Header image by Klawe Rzeczy

Reporters: Simon Lock and Rob Davies

Additional reporting: Ed Siddons, Timo Schober and Jan Marchart

Enablers editor: Eleanor Rose

Impact producer: Lucy Nash

Bureau editor: Franz Wild

Production editor: Frankie Goodway and Alex Hess

Fact checker: Josephine Moulds

Our Enablers project is funded by Open Society Foundations, the Hollick Family Foundation, Sigrid Rausing Trust, the Joffe Trust and out of Bureau core funds. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.

-

Subject:

-

Area: