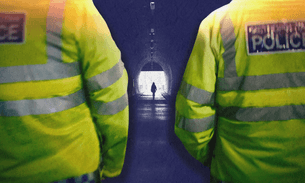

Police face super-complaint over officers’ domestic abuse scandals

Police forces in England and Wales are facing a super-complaint over their handling of domestic abuse allegations made against officers, after a Bureau investigation revealed that police employees were less likely to be convicted than members of the public.

A super-complaint is a new legal device brought in last year to help groups challenge endemic problems in policing.

Lawyers from the Centre for Women’s Justice (CWJ) started preparing the challenge earlier this year after the Bureau found that of nearly 700 reports of police-perpetrated domestic abuse over three years, less than a quarter had ended in professional disciplinary action.

We spoke to multiple women across the UK who felt their abusive police officer partners had used their professional positions to further intimidate and harass them. While some had been too afraid to ever report their abuse, those who did said the forces employing their perpetrators did not take their allegations seriously.

Several more women have approached the Bureau since publication to share similar experiences, including some who were employed by the police alongside their abusers.

Yet more cases have hit headlines recently. Whistleblowers told WalesOnline how a “laddish culture” at Gwent Police had led to concerns that some members of the force had covered up for a colleague who had been controlling and physically abusive to younger female trainees he had dated.

PC Clarke Joslyn was allowed to remain in his post after a new recruit 10 years his junior, Jodie*, reported him for controlling behaviour and stalking. A disciplinary panel later found that he had used controlling behaviour, that he had threatened to “end her” if she humiliated him and that he had physically assaulted her by grabbing her neck and applying pressure. He had eventually left Jodie alone when he started dating Sarah, an even younger trainee.

Sarah told the Bureau she reported Joslyn for coercive and controlling behaviour and several assaults — including an allegation of pinning her to the wall while holding a knife — but he was never arrested.

She said she felt Gwent Police’s response had been almost laughable. “I would describe it as an absolute joke, I can’t think of any other words,” she said.

She believes their failure to act adequately was an attempt to protect the force’s reputation. “I think they thought ... ‘We can’t let this get out now because if her story gets out we’re going to have to dig up the past 20 years, and admit fault for not dealing with all the other reports or indicators we had’.”

She said she believed sexism could be partly behind Gwent’s failure to take the women’s allegations seriously enough. “Females have got a shit time in the police force and they are looked down upon.”

Whatever the reason, Sarah said she embodies the consequences of the force’s failure to act on Jodie’s reports. “He was allowed to stay on in the force and meet me,” she said.

Joslyn was eventually suspended on full pay for four years while allegations by four women, including Jodie and Sarah, were investigated. He resigned before his misconduct hearing, during which he told the panel in written evidence that the complaints against him were “fabricated, misrepresented and exaggerated”.

The panel found on the balance of probabilities that the claims were proven. They said he would have been dismissed if he had not already quit.

Sarah and Jodie now plan to sue Gwent Police for negligence.

The recent leaking of a wide-reaching inquiry by the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner in Scotland into an alleged “boys’ club” of sexist officers in the Moray command area shows how widespread concerns over these problems are.

Some male officers allegedly started bullying a female colleague after she reported her ex-partner, also a Moray officer, for domestic violence. It was reported that officers tricked her into leaving the station with them at night by telling her that her ex-partner was about to arrive. They then drove her to a forest and left her there with no means of transport, allegedly “to teach her a lesson”.

Both male and female officers made complaints of bullying by the “club”.

The CWJ will formally submit their super-complaint in the coming weeks, requesting an institutional investigation into practices and systemic problems at forces across the country.

Harriet Wistrich, the founder-director of the CWJ, said: “We are assembling case studies from around the country where women in relationships with male police officers who have abused them are fearful of reporting and are frequently failed and victimised when they do.”

After submission the challenge will be reviewed by the College of Policing, the Independent Office for Police Conduct and Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services.

The super-complaint will suggest that police leaders need to make better provisions in their procedures to mitigate for the unique potential intimidation police domestic abusers can wield and the lack of confidence felt by their victims when their accused abusers work with those investigating their behaviour.

“He told me, ‘I’m a police officer, no one’s going to believe you’,” one woman, Lucy*, told the Bureau. Her coercive and financially controlling ex-husband remains a serving officer.

“I became suicidal and one day walked to a local bridge with the intent to jump. I called the police for help but instead of taking me to a place of safety, they returned me home to him, despite me asking them not to. When I arrived home he told the officers, ‘Alright mate, I’ll sort her out’, shook their hands, and they left.”

Lucy claims officers from his force gave him a copy of her statement, then later lost it entirely. She alleges the police did not show up when she reported him for breaking into her home after they split up.

The Bureau found through Freedom of Information requests that less than a third of 38 forces across the UK had specific steps in place to ensure impartiality in dealing with domestic abuse by officers, such as taking the suspect to a different station or appointing an investigating officer not known to the suspect.

In the Gwent case, Sarah said her allegations against Joslyn were investigated by someone who already knew him. “The longer you’re in the force the more people you know ... the more friends you make, the more manipulative you can be.”

Concerns about a force’s reputation are apparent in other cases too. Diane*, a civilian employee at a different force, said her report of rape against an ex-partner who was also a staff member had to undergo several “peer reviews” before the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) could make a charging decision, which she was told was because the case involved two police workers.

After the CPS told Diane it would be charging her ex-partner, she alleges, a senior police officer requested another review because of the potential to bring the force into disrepute. In the event no charges were brought.

Despite the allegations, her ex-partner was not moved to a different office. She now feels unable to work there.

“The ongoing daily impact is having a huge detriment to my wider family as well as myself,” Diane said. “There are no words. The police deny that there’s been any wrongdoing on his part, yet the house is alarmed and we’re still living in fear. I believe the stalking is still taking place.”

In response to the Bureau’s initial findings in May, MPs, a police and crime commissioner, women’s rights campaigners and lawyers suggested any police service asked to investigate one of its own employees for domestic abuse should instead transfer the case to a different force.

The Bureau knows of only three forces where this is policy: Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Bedfordshire, although even then the appointment of another force is only a suggestion for “serious or sensitive cases”.

Laura*, who contacted the Bureau after publication, said her abusive partner worked for one of these forces, and that her confidence in the police was only restored after the investigation was transferred.

“It was the general lack of interest at [my partner’s] force,” she said. Laura felt “they were completely uninterested in dealing with it. There was no urgency.”

Her partner’s force interviewed and bailed him after she reported him for alleged rape, but soon closed their criminal investigation. The case was then passed to the second force for an internal misconduct investigation, where Laura says the assigned officer told her the seals had never been broken on the evidence she had provided.

“She was astounded,” she said. The officer asked if Laura would allow her to reinvestigate it as a criminal case. “This was the only officer who did her job properly.” While the first force had never offered to have any alarms installed on her house, she said, the officer at the second had it done immediately. “There was a complete contrast in attitude.”

Nogah Ofer, the solicitor at CWJ who is leading the super-complaint, said: “We will be proposing that such cases should be dealt with outside the police force concerned, with more robust systems and a clear separation between the investigators and the parties involved.”

Gwent Police told the Bureau: "Mr Clarke Joslyn was subject to a misconduct hearing on 5th November 2018 following a thorough and robust inquiry by Gwent Police Professional Standards Department. Mr Clarke Joslyn resigned from Gwent Police prior to the hearing. The hearing continued in his absence and the panel determined that had he remained as an officer he would have been dismissed from Gwent Police."

Police Scotland said it was “supporting the ongoing investigation by the Police Investigations and Review Commissioner. Following the conclusion of all PIRC and Crown related inquiries Police Scotland will address any outstanding conduct complaints."

*All the women's names have been changed and the forces not disclosed due to legal and ethical concerns.

Header illustration by Danny Noble

Our reporting on domestic violence is part of our Bureau Local project, which has many funders. None of our funders have any influence over the Bureau’s editorial decisions or output.